Spermatogenesis is the process by which male primary sperm cells undergo meiosis and produce a number of cells calls spermatogonia, from which the primary spermatocytes are derived. Each primary spermatocyte divides into two secondary spermatocytes and each secondary spermatocyte into two spermatids or young spermatozoa. These develop into mature spermatozoa, also known as sperm cells. Thus, the primary spermatocyte gives rise to two cells, the secondary spermatocytes, which in turn produce four spermatozoa.

Male Gametogenesis

Spermatozoa are the mature male gametes in many sexually reproducing organisms. Spermatogenesis is the male version of gametogenesis and results in the formation of spermatocytes possessing half the normal complement of genetic material. In mammals, it occurs in the male testes and epididymis in a stepwise fashion that takes approximately 64 days.

Spermatogenesis, essential for sexual reproduction is highly dependent upon optimal conditions to occur correctly. DNA methylation and histone modification have been implicated in the regulation of this process. It starts at puberty and usually continues uninterrupted until death, although a slight decrease can be discerned in the quantity of sperm produced with increase in age.

Steps in Spermatogenesis

1) Spermatocytogenesis: Mitotic division of a diploid spermatogonium that resides in the basal compartment of the seminiferous tubules, resulting in two diploid intermediate cells called primary spermatocytes.

Each primary spermatocyte then moves into the adluminal compartment of the seminiferous tubules, duplicates its DNA, and subsequently undergoes meiosis I to produce two haploid secondary spermatocytes.

Secondary spermatocytes later divide into haploid spermatids. During this division, random inclusion of either parental chromosome and chromosomal crossover both increase the genetic variability of the gamete.

Each cell division from a spermatogonium to a spermatid is incomplete; the cells remain connected to one another by bridges of cytoplasm to allow synchronous development. Not all spermatogonia divide to produce spermatocytes; otherwise, the supply would run out. Instead, certain types of spermatogonia divide to produce copies of themselves, thereby ensuring a constant supply of gametogonia to fuel spermatogenesis.

2) Spermatidogenesis: The creation of spermatids from secondary spermatocytes. Secondary spermatocytes produced earlier rapidly enter meiosis II and divide to produce haploid spermatids. The brevity of this stage means that secondary spermatocytes are rarely seen in histological preparations.

3) Spermiogenesis: At this stage, each spermatid begins to grow a tail and develop a thickened midpiece where the mitochondria gather and form an axoneme. Spermatid DNA also undergoes packaging, becoming highly condensed. The DNA is packaged with specific nuclear basic proteins, which are subsequently replaced with protamines during spermatid elongation. The resultant tightly packed chromatin is transcriptionally inactive. The Golgi apparatus surrounds the now condensed nucleus, becoming the acrosome. One of the centrioles of the cell elongates to become the tail of the sperm.

The non-motile spermatozoa are transported to the epididymis in testicular fluid secreted by the Sertoli cells with the aid of peristaltic contraction. While in the epididymis, the spermatozoa gain motility and become capable of fertilization. However, transport of the mature spermatozoa through the remainder of the male reproductive system is achieved via muscle contraction rather than the spermatozoon's recently acquired motility.

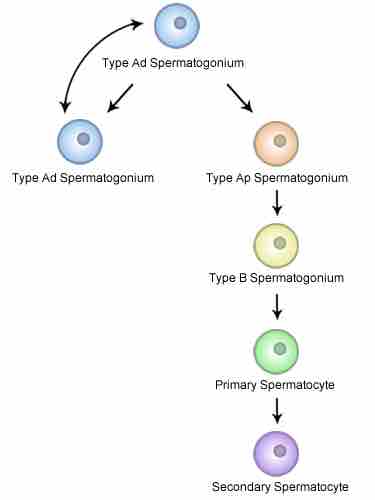

Spermatocytogenesis

Diagram of the steps of spermatocytogenesis, including type Ad spermatogonium, type Ap Spermatogonium, type B spermatogonium, primary spermatocyte, and secondary spermatocyte.

Physiology of Spermatogenesis

Maturation takes place under the influence of testosterone, which removes the remaining unnecessary cytoplasm and organelles. The excess cytoplasm, known as residual bodies, is phagocytosed by surrounding Sertoli cells in the testes. The resulting spermatozoa are now mature but lack motility, rendering them sterile. The mature spermatozoa are released from the protective Sertoli cells into the lumen of the seminiferous tubule in a process called spermiation.

Spermatogenesis is highly sensitive to fluctuations in the environment, particularly hormones and temperature. Seminiferous epithelium is sensitive to elevated temperature in humans and is adversely affected by temperatures as high as normal body temperature. Consequently, the testes are located outside the body in a sack of skin called the scrotum. The optimal temperature is maintained at 2 °C below body temperature in human males. This is achieved by regulation of blood flow and positioning towards and away from the heat of the body by the cremaster muscle and the dartos smooth muscle in the scrotum. Dietary deficiencies (such as vitamins B, E, and A), anabolic steroids, metals (cadmium and lead), x-ray exposure, dioxin, alcohol, and infectious diseases will also adversely affect the rate of spermatogenesis.

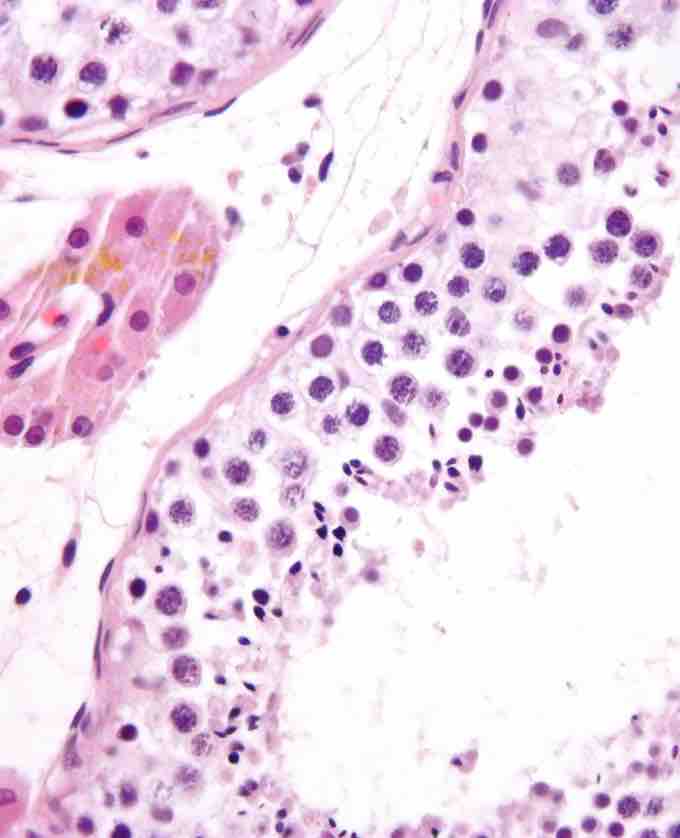

Seminiferous Tubule

Micrograph showing seminiferous tubule with maturing sperm.

Spermatozoon

Diagram of parts of a spermatozoon, including the acrosome, plasma membrane, nucleus, centriole, mitochondria, terminal disc, axial filament, tail, endpiece, midpiece, and head.