Carl Rogers was a prominent psychologist and one of the founding members of the humanist movement. Along with Abraham Maslow, he focused on the growth potential of healthy individuals and greatly contributed to our understanding of the self and personality. Both Rogers’ and Maslow’s theories focus on individual choices and do not hold that biology is deterministic. They emphasized free will and self-determination, with each individual desiring to become the best person they can become.

Humanistic psychology emphasized the active role of the individual in shaping their internal and external worlds. Rogers advanced the field by stressing that the human person is an active, creative, experiencing being who lives in the present and subjectively responds to current perceptions, relationships, and encounters. He coined the term actualizing tendency, which refers to a person's basic instinct to succeed at his or her highest possible capacity. Through person-centered counseling and scientific therapy research, Rogers formed his theory of personality development, which highlighted free will and the great reservoir of human potential for goodness.

Carl Rogers

Carl Rogers was a prominent humanistic psychologist who is known for his theory of personality that emphasizes change, growth, and the potential for human good.

Personality Development and the Self-Concept

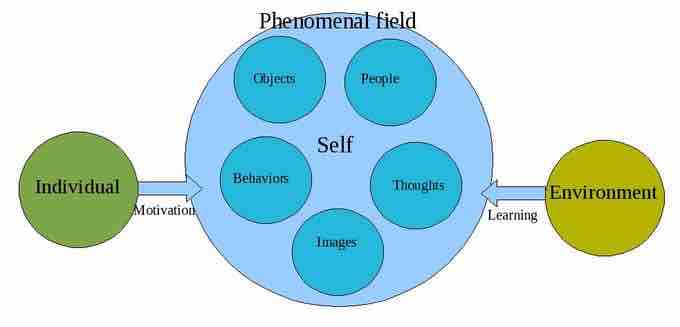

Rogers based his theories of personality development on humanistic psychology and theories of subjective experience. He believed that everyone exists in a constantly changing world of experiences that they are at the center of. A person reacts to changes in their phenomenal field, which includes external objects and people as well as internal thoughts and emotions.

The phenomenal field

The phenomenal field refers to a person's subjective reality, which includes external objects and people as well as internal thoughts and emotions. The person's motivations and environments both act on their phenomenal field.

Rogers believed that all behavior is motivated by self-actualizing tendencies, which drive a person to achieve at their highest level. As a result of their interactions with the environment and others, an individual forms a structure of the self or self-concept—an organized, fluid, conceptual pattern of concepts and values related to the self. If a person has a positive self-concept, they tend to feel good about who they are and often see the world as a safe and positive place. If they have a negative self-concept, they may feel unhappy with who they are.

Ideal Self vs. Real Self

Rogers further divided the self into two categories: the ideal self and the real self. The ideal self is the person that you would like to be; the real self is the person you actually are. Rogers focused on the idea that we need to achieve consistency between these two selves. We experience congruence when our thoughts about our real self and ideal self are very similar—in other words, when our self-concept is accurate. High congruence leads to a greater sense of self-worth and a healthy, productive life. Conversely, when there is a great discrepancy between our ideal and actual selves, we experience a state Rogers called incongruence, which can lead to maladjustment.

Unconditional Positive Regard

In the development of the self-concept, Rogers elevated the importance of unconditional positive regard, or unconditional love. People raised in an environment of unconditional positive regard, in which no preconceived conditions of worth are present, have the opportunity to fully actualize. When people are raised in an environment of conditional positive regard, in which worth and love are only given under certain conditions, they must match or achieve those conditions in order to receive the love or positive regard they yearn for. Their ideal self is thereby determined by others based on these conditions, and they are forced to develop outside of their own true actualizing tendency; this contributes to incongruence and a greater gap between the real self and the ideal self.

"The Good Life"

Rogers described life in terms of principles rather than stages of development. These principles exist in fluid processes rather than static states. He claimed that a fully functioning person would continually aim to fulfill his or her potential in each of these processes, achieving what he called "the good life." These people would allow personality and self-concept to emanate from experience. He found that fully functioning individuals had several traits or tendencies in common:

- A growing openness to experience–they move away from defensiveness.

- An increasingly existential lifestyle–living each moment fully, rather than distorting the moment to fit personality or self-concept.

- Increasing organismic trust–they trust their own judgment and their ability to choose behavior that is appropriate for each moment.

- Freedom of choice–they are not restricted by incongruence and are able to make a wide range of choices more fluently. They believe that they play a role in determining their own behavior and so feel responsible for their own behavior.

- Higher levels of creativity–they will be more creative in the way they adapt to their own circumstances without feeling a need to conform.

- Reliability and constructiveness–they can be trusted to act constructively. Even aggressive needs will be matched and balanced by intrinsic goodness in congruent individuals.

- A rich full life–they will experience joy and pain, love and heartbreak, fear and courage more intensely.

Criticisms of Rogers' Theories

Like Maslow's theories, Rogers' were criticized for their lack of empirical evidence used in research. The holistic approach of humanism allows for a great deal of variation but does not identify enough constant variables to be researched with true accuracy. Psychologists also worry that such an extreme focus on the subjective experience of the individual does little to explain or appreciate the impact of society on personality development.