Many psychologists believe that the total number of personality traits can be reduced to five factors, with all other personality traits fitting within these five factors. According to this model, a factor is a larger category that encompasses many smaller personality traits. The five factor model was reached independently by several different psychologists over a number of years.

History and Overview

Investigation into the five factor model started in 1949 when D.W. Fiske was unable to find support for Cattell's expansive 16 factors of personality, but instead found support for only five factors. Research increased in the 1980s and 1990s, offering increasing support for the five factor model. The five factor personality traits show consistency in interviews, self-descriptions, and observations, as well as across a wide range of participants of different ages and from different cultures. It is the most widely accepted structure among trait theorists and in personality psychology today, and the most accurate approximation of the basic trait dimensions (Funder, 2001).

Because this model was developed independently by different theorists, the names of each of the five factors—and what each factor measures—differ according to which theorist is referencing it. Paul Costa's and Robert McCrae's version, however, is the most well-known today and the one called to mind by most psychologists when discussing the five factor model. The acronym OCEAN is often used to recall Costa's and McCrae's five factors, or the Big Five personality traits: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism.

The Big Five Personality Traits

Openness to Experience (inventive/curious vs. consistent/cautious)

This trait includes appreciation for art, emotion, adventure, unusual ideas, curiosity, and variety of experience. Openness reflects a person's degree of intellectual curiosity, creativity, and preference for novelty and variety. It is also described as the extent to which a person is imaginative or independent; it describes a personal preference for a variety of activities over a strict routine. Those who score high in openness to experience prefer novelty, while those who score low prefer routine.

Conscientiousness (efficient/organized vs. easy-going/careless)

This trait refers to one's tendency toward self-discipline, dutifulness, competence, thoughtfulness, and achievement-striving (such as goal-directed behavior). It is distinct from the moral implications of "having a conscience"; instead, this trait focuses on the amount of deliberate intention and thought a person puts into his or her behavior. Individuals high in conscientiousness prefer planned rather than spontaneous behavior and are often organized, hardworking, and dependable. Individuals who score low in conscientiousness take a more relaxed approach, are spontaneous, and may be disorganized. Numerous studies have found a positive correlation between conscientiousness and academic success.

Extraversion (outgoing/energetic vs. solitary/reserved)

An individual who scores high on extraversion is characterized by high energy, positive emotions, talkativeness, assertiveness, sociability, and the tendency to seek stimulation in the company of others. Those who score low on extraversion prefer solitude and/or smaller groups, enjoy quiet, prefer activities alone, and avoid large social situations. Not surprisingly, people who score high on both extroversion and openness are more likely to participate in adventure and risky sports due to their curious and excitement-seeking nature (Tok, 2011).

Agreeableness (friendly/compassionate vs. cold/unkind)

This trait measures one's tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic towards others. It is also a measure of a person's trusting and helpful nature and whether that person is generally well-tempered or not. People who score low on agreeableness tend to be described as rude and uncooperative.

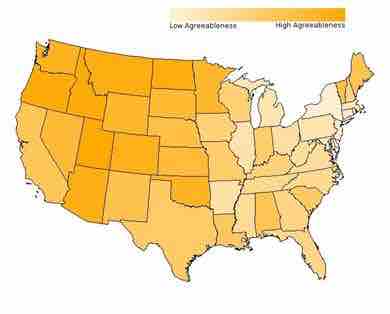

Agreeableness across the United States

Some researchers are interested in examining the way in which traits are distributed within a population. This image shows a general measure of how individuals in each state fall along the five factor trait of agreeableness. The Western states tend to measure high in agreeableness.

Neuroticism (sensitive/nervous vs. secure/confident)

High neuroticism is characterized by the tendency to experience unpleasant emotions, such as anger, anxiety, depression, or vulnerability. Neuroticism also refers to an individual's degree of emotional stability and impulse control. People high in neuroticism tend to experience emotional instability and are characterized as angry, impulsive, and hostile. Watson and Clark (1984) found that people reporting high levels of neuroticism also tend to report feeling anxious and unhappy. In contrast, people who score low in neuroticism tend to be calm and even-tempered.

The Big Five Personality Traits

In the five factor model, each person has five traits (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism) which are scored on a continuum from high to low. In the center column, notice that the first letter of each trait spells the mnemonic OCEAN.

It is important to keep in mind that each of the five factors represents a range of possible personality types. For example, an individual is typically somewhere in between the two extremes of "extraverted" and "introverted", and not necessarily completely defined as one or the other. Most people lie somewhere in between the two polar ends of each dimension. It’s also important to note that the Big Five traits are relatively stable over our lifespan, but there is some tendency for the traits to increase or decrease slightly. For example, researchers have found that conscientiousness increases through young adulthood into middle age, as we become better able to manage our personal relationships and careers (Donnellan & Lucas, 2008). Agreeableness also increases with age, peaking between 50 to 70 years (Terracciano, McCrae, Brant, & Costa, 2005). Neuroticism and extroversion tend to decline slightly with age (Donnellan & Lucas; Terracciano et al.).

Criticisms of the Five Factor Model

Critics of the trait approach argue that the patterns of variability over different situations are crucial to determining personality—that averaging over such situations to find an overarching "trait" masks critical differences among individuals.

Critics of the five-factor model in particular argue that the model has limitations as an explanatory or predictive theory and that it does not explain all of human personality. Some psychologists have dissented from the model because they feel it neglects other domains of personality, such as religiosity, manipulativeness/machiavellianism, honesty, sexiness/seductiveness, thriftiness, conservativeness, masculinity/femininity, snobbishness/egotism, sense of humor, and risk-taking/thrill-seeking.

Factor analysis, the statistical method used to identify the dimensional structure of observed variables, lacks a universally recognized basis for choosing among solutions with different numbers of factors. A five-factor solution depends, on some degree, on the interpretation of the analyst. A larger number of factors may, in fact, underlie these five factors; this has led to disputes about the "true" number of factors. Proponents of the five-factor model have responded that although other solutions may be viable in a single dataset, only the five-factor structure consistently replicates across different studies.

Another frequent criticism is that the five-factor model is not based on any underlying theory; it is merely an empirical finding that certain descriptors cluster together under factor analysis. This means that while these five factors do exist, the underlying causes behind them are unknown.