THE BABY BOOM AND THE ROLE OF WOMEN

The decade following World War II was characterized by growing wealth throughout much of American society: the American economy grew dramatically, expanding at a rate of 3.5% per annum between 1945 and 1970. As economic prosperity empowered couples who had postponed marriage and parenthood, the birth rate started shooting up in 1941, paused in 1944-45 (with 12 million men in service), and then continued to soar until reaching a peak in the late 1950s - a phenomenon known as the post-war baby boom.

In 1946, live births in the United States surged from 222,721 in January to 339,499 in October. By the end of the 1940s, about 32 million babies had been born, compared with 24 million in the 1930s. Sylvia Porter, a columnist for the New York Post, first used the term "boom" to refer to the phenomenon of increased births in post-war America in May of 1951. Annual births first topped four million in 1954 and did not drop below that figure until 1965, by which time four out of ten Americans were under the age of 20.

There are many factors that contributed to the baby boom. In the years after the war, couples who could not afford families during the Great Depression made up for lost time. The mood was now optimistic. During the war, unemployment ended and the economy greatly expanded. Millions of veterans returned home and were forced to reintegrate into society. To facilitate the integration process, Congress passed the G.I. Bill of Rights. This bill encouraged home ownership and investment in higher education through the distribution of loans to veterans at low or no interest rates. The G.I. Bill enabled record numbers of people to finish high school and attend college. This led to an increase in stock of skills and yielded higher incomes to families.

Returning veterans married, started families, pursued higher education, and bought their first homes. With veteran's benefits, the twenty-somethings found new homes in planned communities on the outskirts of American cities. Marriage rates rose sharply in the 1940s and reached all-time highs. Americans began to marry at a younger age: the average age of a person at their first marriage dropped to 22.5 years for males and 20.1 for females, down from 24.3 for males and 21.5 for females in 1940. Getting married immediately after high school was becoming commonplace and women were increasingly under tremendous pressure to marry by the age of 20. The stereotype developed that women were going to college to earn their M.R.S. (Mrs.) degree.

The role of women in American society became an issue of particular interest in the post-war years, with marriage and feminine domesticity depicted as the primary goal for the American woman. As women had been forced out of the labor market by men returning from the military service, many chafed at the social expectations of being an idle stay-at-home housewife who cooked, cleaned, shopped, and tended to children. In 1963, Betty Friedan publisher her book The Feminine Mystique which strongly criticized the role of women during the postwar years and was a best-seller and a major catalyst of the women's liberation movement.

RELIGIOUS RESURGENCE

As the birth rate soared, families grew, and more people moved to the suburbs, the United States witnessed a subsequent boom in affiliation with organized religion, especially various Protestant churches. Between 1950 and 1960, church membership among Americans increased from 49% to 69%. Religious messages began to infiltrate popular culture as religious leaders became famous faces and numerous religious organizations were formed. Institutionalized religion became such a critical aspect of American life that it shaped major political decisions. Although in 1948, Dwight Eisenhower referred to himself as "one of the most deeply religious men [he knew]" yet unattached to any "sect or organization," he decided to get baptized in the Presbyterian Church in 1953, the first year of his presidency. A year later, Congress added the words "under God" to the Pledge of Allegiance.

The 1950s saw a boom in the Evangelical church in America. The post–World War II prosperity experienced in the U.S. also had its effects on the church. Church buildings were erected in large numbers, and the Evangelical church's activities grew along with this expansive physical growth. In the southern U.S., the Evangelicals, represented by leaders such as Billy Graham, have experienced a notable surge displacing the caricature of the pulpit pounding country preachers of fundamentalism although the stereotypes have gradually shifted. Graham began the trend of national celebrity ministers who broadcast to megachurches via radio and television. Additionally, he is notable for having been a spiritual adviser to several United States Presidents, including Dwight D. Eisenhower and Richard Nixon.

In the post–World War II period, a split developed between Evangelicals. Many Evangelicals began to express reservations about being known to the world as fundamentalists. The term neo-evangelicalism was coined in 1947 to identify a distinct movement within self-identified fundamentalist Christianity at the time. The new generation of Evangelicals set as their goal to abandon a militant Bible stance. Instead, they would pursue dialogue, intellectualism, non-judgmentalism, and appeasement. They further called for an increased application of the gospel to the sociological, political, and economic areas. In addition, Christianity Today was first published in 1956. 1956 also marked the beginning of Bethany Fellowship, a small press that grew to be a leading evangelical press. The self-identified fundamentalists also cooperated in separating their "neo-Evangelical" opponents from the fundamentalist name, by increasingly seeking to distinguish themselves from the more open group, whom they often characterized derogatorily by "neo-Evangelical" or just Evangelical.

The Conservative Baptist Association also emerged in 1947 as part of the continuing Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy within the Northern Baptist Convention. The forming churches were fundamentalist/conservative churches that had remained in cooperation with the Northern Baptist Convention after other churches had left, such as those that formed the General Association of Regular Baptist Churches.

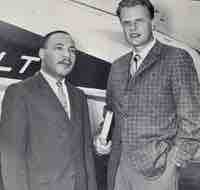

Reverends King and Graham

A photo of popular Christian Reverend Billy Graham with Martin Luther King.

SEPARATION OF CHURCH AND STATE

As the resurgence of religion continued to grow in the United States, a number of landmark Supreme Court cases addressed the issue of the separation of church and state. The centrality of the "separation" concept to the Religion Clauses of the Constitution was made explicit in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), a case that dealt with a New Jersey law that allowed government funds for transportation to religious schools. Though the ruling was upheld, this was the first case in which the court applied the Establishment Clause to the laws of a state, having interpreted the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as applying the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal legislature. Citing Jefferson, the court concluded that "The First Amendment has erected a wall between church and state. That wall must be kept high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach."

In 1962, the Supreme Court addressed the issue of officially-sponsored prayer or religious recitations in public schools. In Engel v. Vitale (1962), the Court determined it unconstitutional for state officials to compose an official school prayer and require its recitation in public schools, even when the prayer is non-denominational and students may excuse themselves from participation.