Utopian Communities of the Nineteenth Century

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many radical religious groups formed utopian societies in which all aspects of people's lives could be governed by their faith. Experimental communities sprang up, created by men and women who hoped not only to create a better way of life but also to recast American civilization so that greater equality and harmony would prevail. Indeed, some of these reformers envisioned the creation of alternative ways of living that would allow people to attain perfection in human relations.

A number of religious utopian societies from Europe came to the United States beginning in the eighteenth century and continuing throughout the nineteenth century, including the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness (led by Johannes Kelpius), the Ephrata Cloister, the Shakers, and the Harmony Society. Communities such as Fruitlands were largely based on transcendentalist principles; others such as the Oneida Community were based on perfectionistic ideals and embraced unorthodox sexual practices. Many utopianist groups also believed in millennialism, or chiliasm in Greek. Millennialism is a belief held by some Christian denominations that there will be a "golden age" or "paradise on earth" in which Christ will reign for 1,000 years prior to the final judgment and future eternal state.

Most of those attracted to utopian communities had been profoundly influenced by evangelical Protestantism, especially the Second Great Awakening. However, their experience of revivalism had left them wanting to further reform society. The communities they formed and joined adhered to various socialist ideas and were considered radical because members wanted to create a new social order, not reform the old.

The Shakers

One of the earliest utopian movements was the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly known as the Shakers. Originating in England in the eighteenth century and moving to America shortly afterward, the Shakers are a Christian Protestant religious sect whose name was derived from the movements of the members in dancing, which forms a part of their worship. Ann Lee, a leader of the group in England, emigrated to New York in the 1770s, having experienced a profound religious awakening that convinced her that she was “mother in Christ.” She taught that God was both male and female; Jesus embodied the male side, while Mother Ann (as she came to be known by her followers) represented the female side. To Shakers in both England and the United States, Mother Ann represented the completion of divine revelation and the beginning of the millennium of heaven on earth.

In practice, men and women in Shaker communities were held as equals—a radical departure at the time—and women often outnumbered men. Equality extended to the possession of material goods as well; no one could hold private property. Shaker communities aimed for self-sufficiency, raising food and making all that was necessary, including furniture that emphasized excellent workmanship as a substitute for worldly pleasure.

Members of Shaker communities held all of their possessions in common and lived in a prosperous, inventive, self-supporting society. The defining features of the Shakers were their spiritual mysticism and their prohibition of sexual intercourse, which they held as an example of a lesser spiritual life and a source of conflict between women and men. Rapturous Shaker dances, for which the group gained notoriety, allowed for emotional release. The high point of the Shaker movement came in the 1830s, when about 6,000 members populated communities in New England, New York, Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky. New members only could come from conversions and from children brought to the Shaker villages. The Shakers persisted into the twentieth century and are mostly known today for their cultural contributions (especially their style of music and furniture) and their model of equality of the sexes.

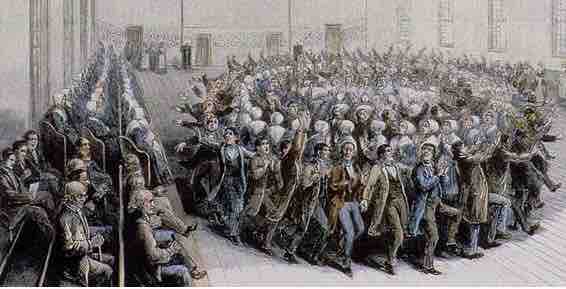

Shaker dancing

Music and dance were important parts of Shaker community worship.

The Harmony Society

The Harmony Society was a Christian theosophy and pietist group founded in Iptingen, Germany, in 1785. Due to religious persecution by the Lutheran Church and the government in Württemberg, the society moved to the United States and settled in Pennsylvania in 1805, together with about 400 followers. They formally organized the Harmony Society, placing all of their goods in common. The Harmony Society made three attempts to effect a millennial society, with the most notable example being at New Harmony, Indiana. Later, Scottish industrialist Robert Owen bought New Harmony and attempted to form a secular utopian community there. The group lasted until 1905, making it one of the longest-running financially successful communes in American history.

The Oneida Community

The Oneida Community, founded by John Humphrey Noyes in Oneida, New York, was a utopian religious commune that lasted from 1848 to 1881. Although this utopian experiment is better known today for its manufacture of Oneida silverware, it was one of the longest running communes in American history. Also known as the "Perfectionist movement," the community believed that Jesus had already returned in 70 A.D., making it possible for them to bring about Jesus's millennial kingdom themselves, to be free of sin, and to be perfect in this world (a belief called "Perfectionism").

Noyes applied his idea of perfection to relationships between men and women, earning notoriety for his unorthodox views on marriage and sexuality. Beginning in his home town of Putney, Vermont, he began to advocate what he called "complex marriage": a form of communal marriage in which women and men who had achieved perfection could engage in sexual intercourse without sin. Noyes also promoted “male continence,” whereby men would not ejaculate, thereby freeing women from pregnancy and the difficulty of determining paternity when they had many partners. Intercourse became fused with spiritual power among Noyes and his followers.

The concept of complex marriage scandalized the townspeople in Putney, so Noyes and his followers moved to Oneida, New York. Individuals who wanted to join the Oneida Community underwent a tough screening process to weed out those who had not reached a state of perfection, which Noyes believed promoted self-control, not out-of-control behavior. The goal was a balance between individuals in a community of love and respect. The perfectionist community Noyes envisioned ultimately dissolved in 1881, although the Oneida Community itself continues to this day.

Fruitlands

Fruitlands was a Utopian agrarian commune established in Harvard, Massachusetts, by Amos Bronson Alcott and Charles Lane in the 1840s, based on transcendentalist principles. Lane purchased what was known as the Wyman farm and its 90 acres, which also included a dilapidated house and barn. Residents of Fruitlands ate no animal substances, drank only water, bathed in unheated water, and did not use artificial light. Property was held communally, and no animal labor was used. The community was short-lived and lasted only seven months.