Introduction

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant revival movement during the early nineteenth century. The movement began around 1790 and gained momentum by 1800; after 1820, membership rose rapidly among Baptist and Methodist congregations, whose preachers led the movement. The Second Great Awakening began to decline by 1870. It enrolled millions of new members and led to the formation of new denominations. It has been described as a reaction against skepticism, deism, and rational Christianity, although why those forces became pressing enough at the time to spark revivals is not fully understood.

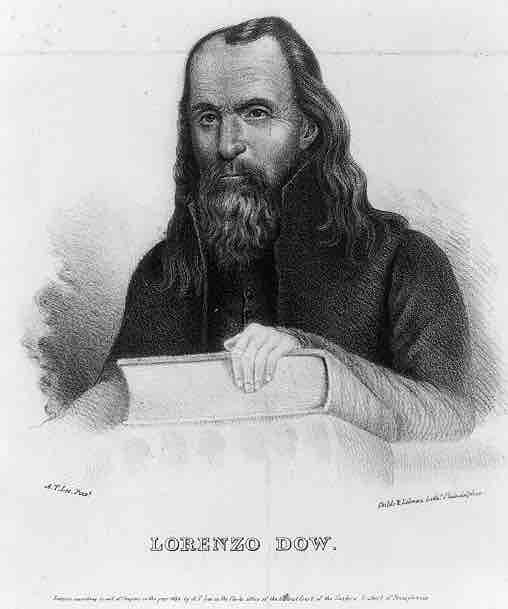

The Second Great Awakening expressed Arminian theology, by which every person could be saved through revivals, repentance, and conversion. Revivals were mass religious meetings featuring emotional preaching by evangelists such as the eccentric Lorenzo Dow. Many converts believed that the Awakening heralded a new millennial age. The Second Great Awakening stimulated the establishment of many reform movements designed to remedy the evils of society before the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

Lorenzo Dow, American itinerant preacher

The Second Great Awakening included large revivals, which were passionate meetings led by evangelist preachers such as the eccentric Lorenzo Dow.

The Second Great Awakening had a profound effect on American religious history. The numerical strength of the Baptists and Methodists rose relative to that of the denominations dominant in the colonial period, such as the Anglicans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Reformed.

Background

The burst of religious enthusiasm that began in Kentucky and Tennessee in the 1790s and early 1800s among Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians owed much to the uniqueness of the early decades of the republic. These years saw swift population growth, broad western expansion, and the rise of participatory democracy. These political and social changes made many people anxious, and the more egalitarian, emotional, and individualistic religious practices of the Second Great Awakening provided relief and comfort for Americans experiencing rapid change. The awakening soon spread to the East, where it had a profound effect on Congregationalists and Presbyterians. The thousands swept up in the movement believed in the possibility of creating a much better world. Many adopted millennialism, the fervent belief that the Kingdom of God would be established on earth and that God would reign on earth for a thousand years, characterized by harmony and Christian morality. Those drawn to the message of the Second Great Awakening yearned for stability, decency, and goodness in the new and turbulent American republic.

Evangelizing the Frontiers

Congregationalists set up missionary societies to evangelize the western territory of the Northern Tier. Members of these groups acted as apostles for the faith, educators, and exponents of northeastern urban culture. The Second Great Awakening served as an organizing process that created, "a religious and educational infrastructure" across the western frontier that encompassed social networks, a religious journalism that provided mass communication, and church-related colleges. Publication and education societies promoted Christian education; most notable among them was the American Bible Society, founded in 1816.

Women made up a large part of these voluntary societies. The Female Missionary Society and the Maternal Association, both active in Utica, New York, were highly organized and financially sophisticated women's organizations responsible for many of the evangelical converts of the New York frontier.

Each denomination that participated in the Second Great Awakening had assets that allowed it to thrive on the frontier. The Methodists had an efficient organization that depended on ministers known as "circuit riders," who sought out people in remote frontier locations. The circuit riders came from among the common people, which helped them establish rapport with the frontier families they hoped to convert.

Relation to Social Reform

Social reform prior to the Civil War came largely out of this new devotion to religion. Efforts to apply Christian teaching to the resolution of social problems presaged the social gospel of the late nineteenth century. Converts were taught that to achieve salvation, they needed not only to repent for personal sin but also work for the moral perfection of society, which meant eradicating sin in all its forms. Thus, evangelical converts were leading figures in a variety of nineteenth-century reform movements.

Reforms took the shape of social movements for temperance, women's rights, and the abolition of slavery. Social activists began efforts to reform prisons and care for the handicapped and mentally ill. They believed in the perfectibility of people and were highly moralistic in their endeavors. Many participants in the revival meetings believed that reform was a part of God's plan. As a result, local churches saw their role in society as purifying the world through the individuals to whom they could bring salvation, as well as through changes in the law and the creation of institutions. Interest in transforming the world was applied to political action, as temperance activists, antislavery advocates, and proponents of other variations of reform sought to implement their beliefs into national politics. While religion had previously played an important role on the American political scene, the Second Great Awakening highlighted the important role which individual beliefs would play.