The Election of 1796

The election of 1796 was the first contested American presidential election and the only one in which a president and vice president were elected from opposing tickets. The ratification of the Twelfth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution would render such a result unlikely in the future. When incumbent President George Washington refused a third term in office, Vice President John Adams became a candidate for the presidency on the Federalist Party ticket, with former Governor Thomas Pinckney of South Carolina as the next most popular Federalist. Their opponents on the Democratic-Republican ticket were former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Senator Aaron Burr. At this point, each man from any party ran alone, as the formal position of running mate on a party ticket had not yet been established.

Thomas Jefferson

1796 Democratic-Republican presidential candidate.

John Adams

1796 Federalist presidential candidate.

The Voting System

In 1796, voters only could cast ballots for electors in the Electoral College, not for the presidential candidates themselves, and not all electors publicly declared their political preferences. Some state legislatures even selected the members of the Electoral College. Moreover, the voting method in the Electoral College did not account for party tickets: The writers of the Constitution had not envisioned competing political factions. There was no way for the electors to cast one vote for president and one for vice president—the electors simply voted for two different people, and the candidate with the most votes became president while the candidate with the second-highest number became vice president.

Though there was no way for electors to differentiate between candidates for president and vice president, both parties informally designated a presidential nominee. The Federalists chose Adams, and the Democratic-Republicans chose Jefferson, with the intention that the entirety of each party’s electors would vote as a unit for the designated choices. This system of balloting was not changed until the Twelfth Amendment (1804), which allowed for the notion of a running mate by stipulating separate balloting for president and vice president.

Political Race and Outcome

Unlike the previous election, of which the outcome had been a foregone conclusion, each party campaigned heavily for its nominee. The campaign was an acrimonious one, and partisan rancor over the French Revolution and the Whiskey Rebellion fueled the divide. Federalists attempted to identify the Democratic-Republicans with the violence of the French Revolution, while the Democratic-Republicans accused the Federalists of favoring monarchism and aristocracy. Democratic-Republicans sought to identify Adams with the policies developed by fellow Federalist Alexander Hamilton during the Washington administration, which they declaimed were too much in favor of Great Britain and a centralized national government. Paradoxically, Hamilton himself opposed Adams and worked to undermine his election.

In foreign policy, Democratic-Republicans denounced the Federalists over Jay's Treaty. Federalists attacked Jefferson's moral character, alleging he was an atheist and a coward during the Revolutionary War. Adams supporters also accused Jefferson of being too supportive of France; this accusation was underscored when the French ambassador embarrassed the Democratic-Republicans by publicly backing Jefferson and attacking the Federalists right before the election.

In the election, Federalist John Adams defeated Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson by a narrow margin of only three electoral votes. Jefferson received the second-highest number of electoral votes and was elected vice president according to the prevailing rules of electoral college voting. This election marked the formation of the first party system and established a permanent rivalry between Federalist New England and the Republican South, with the middle states holding the balance of power.

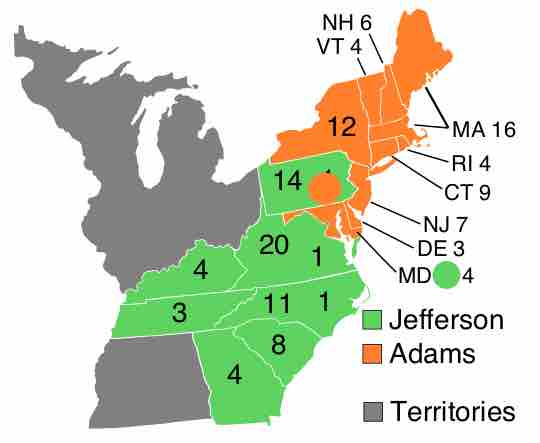

Presidential election of 1796

This map illustrates the 1796 presidential election results, with presidential electoral votes by state. The majority of votes for Jefferson came from the southern states and Pennsylvania, while the majority of votes for Adams came from the northern states.

Consequences

Despite its contention, the 1796 election marked the first peaceful transfer of power between administrations. Washington, who had been reelected in 1792 by an overwhelming majority, refused to run for a third term, thus setting a precedent for future presidents. The following four years, however, would be the only time that the president and vice president of the United States were from different parties. It caused much discord between Adams and Jefferson, with Jefferson leveraging his position as vice president to attack President Adams' policies and Adams alienating Jefferson from all cabinet and policy decisions.

The 1796 election provided the impetus for the Twelfth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. On January 6, 1797, Representative William L. Smith of South Carolina presented a resolution on the floor of the House of Representatives for an amendment that would allow the presidential electors to designate which candidate would be president and which would be vice president. Although this amendment was not adopted until after the 1800 election, the events of 1796 signaled to Congress that some minor adjustments to the Constitution were necessary in order to make the electoral system more efficient and to prevent opposing political factions from holding executive positions at the same time.