The Philippine-American War, also known as the "Philippine War of Independence" or the "Philippine Insurrection" (1899–1902), was an armed conflict between the United States and Filipino revolutionaries. The conflict arose after the Philippine Revolution of 1896, from the First Philippine Republic's struggle to gain independence following annexation by the United States.

The conflict arose when the First Philippine Republic objected to the terms of the Treaty of Paris, under which the United States took possession of the Philippines from Spain after the Spanish-American War.

Fighting erupted between U.S. and Filipino revolutionary forces on February 4, 1899, and quickly escalated into the 1899 Battle of Manila. On June 2, 1899, the First Philippine Republic officially declared war against the United States. The war officially ended on July 2, 1902, with a victory for the United States. However, some Philippine groups led by veterans of the Katipunan continued to battle the American forces. Among those leaders was General Macario Sakay, a veteran Katipunan member who assumed the presidency of the proclaimed "Tagalog Republic," formed in 1902 after the capture of President Emilio Aguinaldo. Other groups, including the Moro people and Pulahanes people, continued hostilities in remote areas and islands until their final defeat a decade later at the Battle of Bud Bagsak on June 15, 1913.

The Battle of Manila

The Battle of Manila, February 1899.

Impact and Legacy

The war with and occupation by the United States would change the cultural landscape of the islands. The war resulted in an estimated 34,000 to 220,000 Philippine casualties (with more civilians dying from disease and hunger brought about by war); the disestablishment of the Roman Catholic Church as the state religion; and the introduction of the English language in the islands as the primary language of government, education, business, and industry, and increasingly in future decades, of families and educated individuals.

Under the 1902 "Philippine Organic Act," passed by the U.S. Congress, Filipinos initially were given very limited self-government, including the right to vote for some elected officials such as a Philippine Assembly. But it was not until 14 years later, with the passage of the 1916 Philippine Autonomy Act (or "Jones Act"), that the United States officially promised eventual independence, along with more Philippine control in the meantime over the Philippines. The 1934 Philippine Independence Act created in the following year the Commonwealth of the Philippines, a limited form of independence, and established a process ending in Philippine independence (originally scheduled for 1944, but interrupted and delayed by World War II). Finally in 1946, following World War II and the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, the United States granted independence through the Treaty of Manila.

American Opposition

Some Americans, notably William Jennings Bryan, Mark Twain, Andrew Carnegie, Ernest Crosby, and other members of the American Anti-Imperialist League, strongly objected to the annexation of the Philippines. Anti-imperialist movements claimed that the United States had become a colonial power by replacing Spain as the colonial power in the Philippines. Other anti-imperialists opposed annexation on racist grounds. Among these was Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina, who feared that annexation of the Philippines would lead to an influx of nonwhite immigrants into the United States. As news of atrocities committed in subduing the Philippines arrived in the United States, support for the war flagged.

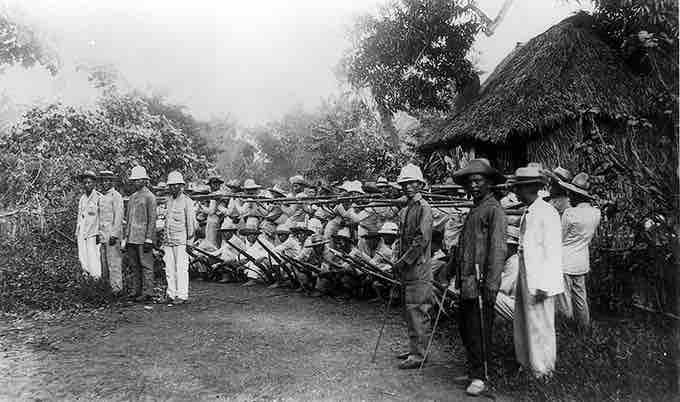

Filipino soldiers

Filipino soldiers outside Manila in 1899.