The term "child labor" refers to the employment of children in any work that deprives them of their childhood, interferes with their ability to attend regular school, and is mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous and harmful. This practice is considered exploitative by many international organizations. Legislations across the world prohibit child labor. These laws do not consider all work by children as child labor; exceptions include work by child artists, supervised training, and other categories of work such as those completed by Amish children.

During the Industrial Revolution, children as young as four were employed in production factories with dangerous, and often fatal, working conditions. In coal mines, children would crawl through tunnels that were too narrow and low to accommodate adults. Children also worked as errand boys, crossing sweepers, and shoe blacks, or they worked selling matches, flowers, and other cheap goods. Some children undertook work as apprentices to respectable trades such as building or as domestic servants.

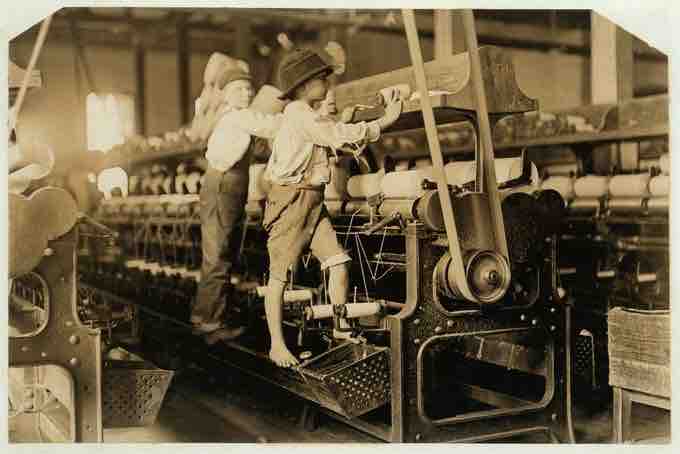

As the United States industrialized, factory owners hired young workers for a variety of tasks. Especially in textile mills, children were often hired together with their parents. Many families in mill towns depended on the children's labor to make enough money for necessities.

Abolishing Child Labor

The National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), an organization dedicated to the abolition of all child labor, was formed in 1904. By publishing information about the lives and working conditions of young workers, the NCLC helped mobilize popular support for state-level child labor laws. These laws often were paired with compulsory education laws that were designed to keep children in school and out of the paid labor market until a specified age (usually 12, 14, or 16 years).

In 1916, the NCLC and the National Consumers League successfully pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the Keating-Owen Act, which was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson. It was the first federal child labor law. However, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the law two years later in Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), declaring that the law violated the Commerce Clause by regulating intrastate commerce. In 1924, Congress attempted to pass a constitutional amendment that would authorize a national child labor law. This measure was blocked, and the bill was eventually dropped.

It took the Great Depression to end child labor nationwide; adults had become so desperate for jobs that they would work for the same wage as children. In 1938, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which, among other things, placed limits on many forms of child labor. However, The 1938 labor law giving protections to working children excludes agriculture. As a result, approximately 500,000 children pick almost a quarter of the food currently produced in the United States.

Compulsory Education

Alongside the abolition of child labor, compulsory education laws also kept children out of abusive labor conditions. The school system remained largely private and unorganized until the 1840s. Public schools were always under local control, with no federal role, and a limited state role. However, by 1900, 34 states had compulsory schooling laws, 4 of which were in the South. 30 states with compulsory schooling laws required attendance until age 14 (or older). As a result, by 1910, 72 percent of American children attended school. Half the nation's children attended one-room schools. In 1918, every state required students to complete elementary school.

Protesting

Two girls protesting child laborers.

Child laborers

A photo of child laborers.