Women in the Workforce

The Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries changed the nature of work for women in Europe and other countries of the Western world. Working for a wage, and eventually a salary, became part of urban life.

The 1870 U.S. census was the first to count "females engaged in each occupation" and provides an intriguing snapshot of women's history. It reveals that, contrary to popular belief, not all American women of the nineteenth century were either idle in their middle-class homes or working in sweatshops. Women were 15 percent of the total workforce (1.8 million out of 12.5). They made up one-third of factory "operatives," but teaching and the occupations of dressmaking, millinery, and tailoring played a larger role. Two-thirds of teachers were women. Women defied the stereotypes of the time by working in iron and steel works, mines, sawmills, oil wells and refineries, gas works, and charcoal kilns. Some even held jobs as ship riggers, teamsters, turpentine laborers, brass founders/workers, shingle and lathe makers, stock-herders, gunsmiths and locksmiths, and hunters and trappers.

The Family

In nineteenth-century farm settings, children were an important part of their families' agricultural livelihoods. As industrialization occurred and families shifted from rural agricultural settings to urban ones, the number of children per household also declined. Children became less of an economic benefit and more of a cost: Urban life necessitated educating children, which was costly.

During the 1910s and 1920s, women delayed childbirth for economic opportunities that were present in urban areas. However, this trend reversed during the Great Depression because of the lower number of economic opportunities available for women. As a result, Depression Era women were more likely to marry and have children earlier. In 1900, roughly 40 percent of single women were employed versus only 5 percent of married women. This 35-percent gap persisted for many years. A study of women college graduates in the twentieth century concluded that those graduating between 1900 and 1920 had to make, “a distinct choice between family and career.”

General Federation of Women's Clubs

The General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC), founded in 1890, is an international women's organization dedicated to community improvement by enhancing the lives of others through volunteer service. GFWC is one of the world's largest and oldest nonpartisan, nondenominational women's volunteer service organizations.

The group holds a congressional charter under Title 36 of the U.S. Code. History of the GFWC traces its roots back to Jane Cunningham Croly, a New York newspaperwoman who wrote under the pen name of "Jennie June." Indignant that she and other women were denied admittance to a banquet honoring Charles Dickens in 1868 at the all-male New York Press Club simply because they were women, she resolved to organize a club for women only.

The name initially chosen for this club was "Sorosis," a Greek word meaning, "an aggregation, a sweet flavor of many fruits." As Sorosis approached its 21st year, Mrs. Croly proposed a conference in New York that brought together delegates from 61 women's clubs. On the last day of the conference, the women took action to form a permanent organization. A committee to draft a constitution and plan of organization to be ratified the following year was chosen, with Sorosis president, Ella Dietz Clymer, presiding. The constitution was adopted in 1890, and the General Federation of Women's Clubs was born. It was chartered in 1901 by the U.S. Congress.

Ella Dietz Clymer holds a particular place of honor in Federation history as the author of the GFWC motto "Unity in Diversity." Speaking to the delegates at the first conference, she said, "We look for unity, but unity in diversity. We hope that you will enrich us by your varied experiences." The aptness of the motto is evident in the diverse interests of GFWC members, who have implemented a broad range of programs and projects tailored to meet the needs of their communities. It set the tone for the flexibility that has allowed the GFWC to grow and adapt its volunteer work to the changing and diverse lifestyles and concerns of women throughout the country.

Local women's clubs initially joined the General Federation directly but later came into membership through state federations that began forming in 1892. The GFWC also counts international clubs among its members. Although women's clubs were founded primarily as a means of self-education and development for women, the emphasis of most local clubs gradually changed to one of community service and improvement.

While not every state in the country has a local women's club, several have remained very active over the last 110 years. The state of Maryland chapter, for example, is held in high regard by the General Federation. In a time when women's rights were suppressed, the State Federation chapters held grassroots efforts to make sure women's voices were heard. Through everything from monthly group meetings to annual charter meetings, women of influential status within their communities could voice their feelings. They were able to meet with state officials in order to have a say in the ongoings of community events. Until the right to vote was granted, these women's clubs were the best outlet for women to be heard and taken seriously.

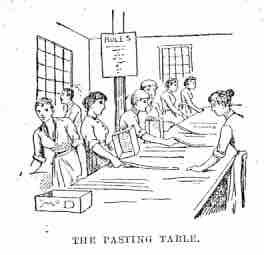

"The Pasting Table"

A 1887 illustration of women working in an assembly line.