The Homestead Strike

The strike by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers (AA) at the Homestead steel mill in 1892 was different from previous large-scale strikes in American history, such as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Great Southwest Railroad Strike of 1886. Earlier strikes had been largely leaderless and disorganized mass uprisings of workers. The Homestead Strike, however, was organized and purposeful, a harbinger of the type of strike that would mark the modern age of labor relations in the United States.

Andrew Carnegie, owner of Carnegie Steel, placed industrialist Henry Clay Frick in charge of his company's operations in 1881. With the collective bargaining agreement due to expire on June 30, 1892, Frick and the leaders of the local AA union entered into negotiations in February. With the steel industry doing well and prices higher, the AA asked for a wage increase; Frick immediately countered with a 22 percent wage decrease that would affect nearly half of the union's membership and remove a number of positions from the bargaining unit. Frick announced on April 30, 1892, that he would bargain for 29 more days. If no contract was reached, Carnegie Steel would cease to recognize the union. Then Frick offered a slightly better wage scale and advised the superintendent to tell the workers, "We do not care whether a man belongs to a union or not, nor do we wish to interfere. He may belong to as many unions or organizations as he chooses, but we think our employees at Homestead Steel Works would fare much better working under the system in vogue at Edgar Thomson and Duquesne."

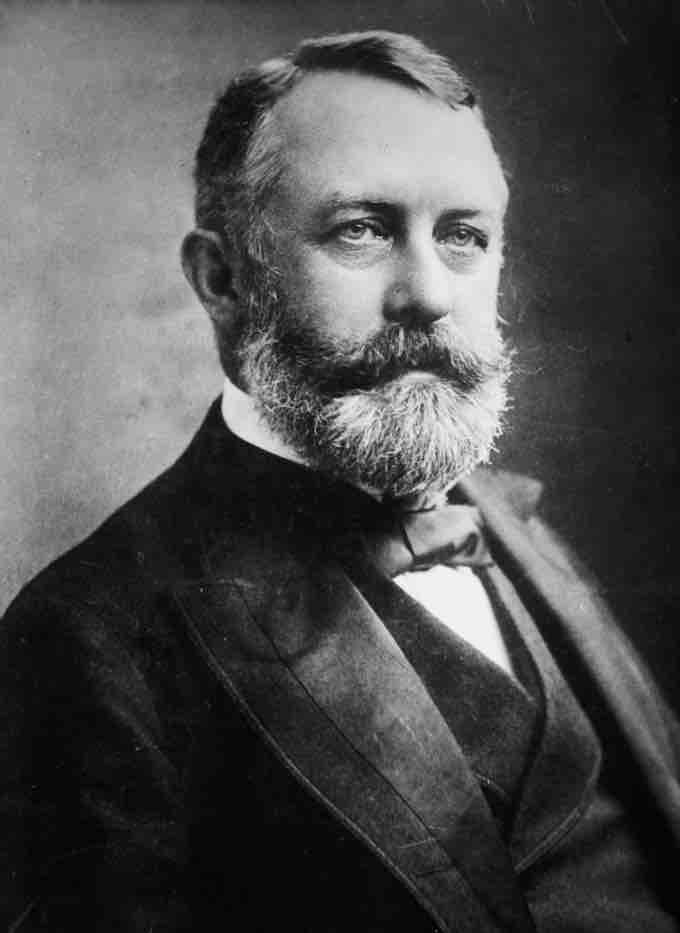

Henry Clay Frick

A portrait of American industrialist and financier Henry Clay Frick.

Lockout

On the evening of June 28, 1892, Frick locked workers out of the plate mill and one of the open hearth furnaces. When no collective bargaining agreement was reached on June 29, Frick locked the union out of the rest of the plant. The Knights of Labor, which had organized the mechanics and transportation workers at Homestead, agreed to walk out alongside the skilled workers of the AA. Workers at Carnegie plants in Pittsburgh, Duquesne, Union Mills, and Beaver Falls went on strike in sympathy the same day.

Strike

The striking workers were determined to keep the plant closed. Picket lines were thrown up around the plant and the town, and 24-hour shifts established. Frick placed ads for replacement workers in newspapers as far away as Boston, St. Louis, and even Europe.

In April 1892, Frick contracted with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency to provide security at the plant. His intent was to open the works with nonunion men on July 6. Carnegie corporate attorney Philander Knox devised a plan to get the Pinkertons onto the mill property. Three hundred agents assembled on the Davis Island Dam on the Ohio River about five miles below Pittsburgh at 10:30 p.m. on the night of July 5, 1892. They were given Winchester rifles, placed on two specially equipped barges, and towed upriver.

The strikers were prepared for them; the AA had learned of the Pinkertons as soon as they had left Boston for the embarkation point. The strikers blew the plant whistle at 2:30 a.m., drawing thousands of men, women, and children to the plant.

The Pinkertons attempted to disembark again at 8:00 a.m. when a striker high up the riverbank fired a shot. The Pinkertons returned fire and four more strikers were killed (one by shrapnel sent flying when cannon fire hit one of the barges). After three agents were shot, many of the Pinkertons refused to continue the firefight. Intermittent gunfire from both sides continued throughout the morning. More than 300 riflemen positioned themselves on the high ground and kept a steady stream of fire on the barges. Just before noon, a sniper shot killed another Pinkerton agent.

At 4:00 p.m., events at the mill quickly began to wind down. The Pinkertons, too, wished to surrender. At 5:00 p.m., they raised a white flag and two agents asked to speak with the strikers. O'Donnell, a heater in the plant and head of the union's strike committee, guaranteed them safe passage out of town. Their arms were stripped from them, and as the Pinkertons crossed the grounds of the mill, the crowd formed a gauntlet through which the agents passed. Men and women threw sand and stones at the Pinkerton agents, spat on them, and beat them. Several Pinkertons were clubbed unconscious. Members of the crowd ransacked the barges, then burned them to the waterline.

The steelworkers resolved to meet the militia with open arms, hoping to establish good relations with the troops. But the militia managed to keep its arrival in the town a secret almost to the last moment. Within 20 minutes they had displaced the picketers; by 10:00 a.m., company officials were back in their offices.

On July 15, the company brought in strikebreakers and new employees (many of them black), relit the furnaces, and restarted production under the protection of the militia. But a race war between nonunion black and white workers in the Homestead plant broke out on July 22, 1892. Desperate to find a way to continue the strike, the AA appealed to Whitelaw Reid, the Republican candidate for vice president, on July 16. The AA offered to make no demands or set any preconditions; the union merely asked that Carnegie Steel reopen the negotiations. Frick, too, needed a way out of the strike. The company could not operate for long with strikebreakers living on the mill grounds, and permanent replacements had to be found.

On July 18, the town was placed under martial law, further disheartening many of the strikers. National attention became riveted on Homestead when Alexander Berkman, a New York anarchist with no connection to steel or to organized labor, plotted with his lover, Emma Goldman, to assassinate Frick. He came in from New York, gained entrance to Frick's office, and then shot and stabbed the executive. Frick survived and continued his role.

The Berkman assassination attempt undermined public support for the union and prompted the final collapse of the strike. The union voted to go back to work on Carnegie's terms; the strike had failed and the union had collapsed.

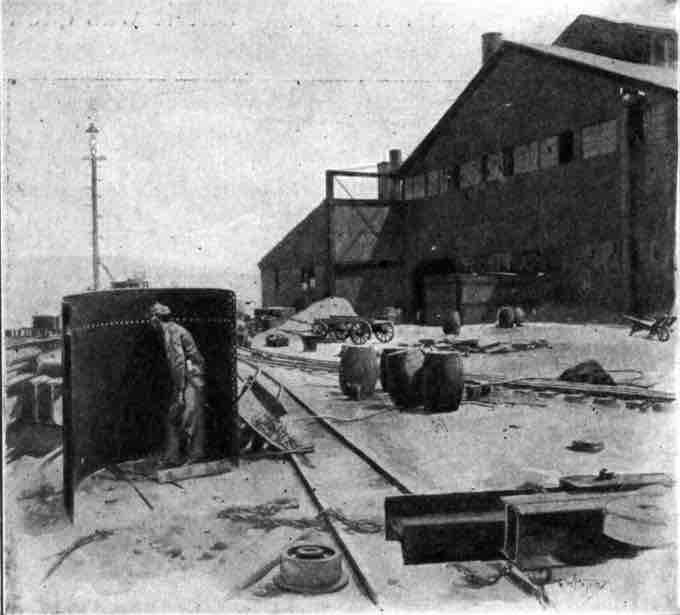

Strikers shield

Demonstration of a shield used by the workers while firing the cannon.