Introduction: The Market Revolution

The Market Revolution (1793–1909) in the United States was a drastic change in the manual-labor system originating in the South (and soon moving to the North) and later spreading to the entire world. Traditional commerce was made obsolete by improvements in transportation, communication, and industry. With the growth of large-scale domestic manufacturing, trade within the United States increased, and dependence on foreign imports declined. The dramatic changes in labor and production at this time included a great increase in wage labor. The agricultural explosion in the South and West and the textile boom in the North strengthened the economy in complementary ways.

The South and the Cotton Gin

Commercial agriculture and domestic manufacturing became crucial sectors of the American economy. In 1793, Eli Whitney's cotton gin revolutionized the cotton industry in the South. The cotton gin (short for cotton engine) was a machine that quickly and easily separated cotton fibers from their seeds, a job that otherwise had to be performed painstakingly by hand, most often by slaves. Whitney went on to develop muskets with interchangeable parts, a technology employed by northern manufacturers in many different industries.

Eli Whitney on U.S. postage issue of 1940

Eli Whitney's crucial contributions to the Market Revolution created a lasting legacy.

Advancements in the West

Many new products revolutionized agriculture in the West as well. John Deere, for example, invented a horse-pulled steel plow to replace the difficult oxen-driven wooden plows that farmers had used for centuries. The steel plow allowed farmers to till soil faster and more cheaply without having to make repairs as often. In the 1830s, Cyrus McCormick's mechanical mower-reaper quintupled the efficiency of wheat farming. Just as southern farmers had prospered after the invention of the cotton gin, farmers in the West raked in huge profits as they conquered more lands from the American Indians to plant more and more wheat. For the first time, farmers began producing more wheat than the West could consume. Rather than let it go to waste, they began to transport crop surpluses to sell in the manufacturing Northeast.

The American System

The importance of the federal government also grew during this period. Congressman Henry Clay introduced the American System to develop internal improvements, protect U.S. industry through tariffs, and create a national bank. Federal and local governments, as well as private individuals, invested in roads, canals, and railroads. The 1825 completion of the Erie Canal was a tremendous engineering feat and opened the West for trade with markets on the east coast.

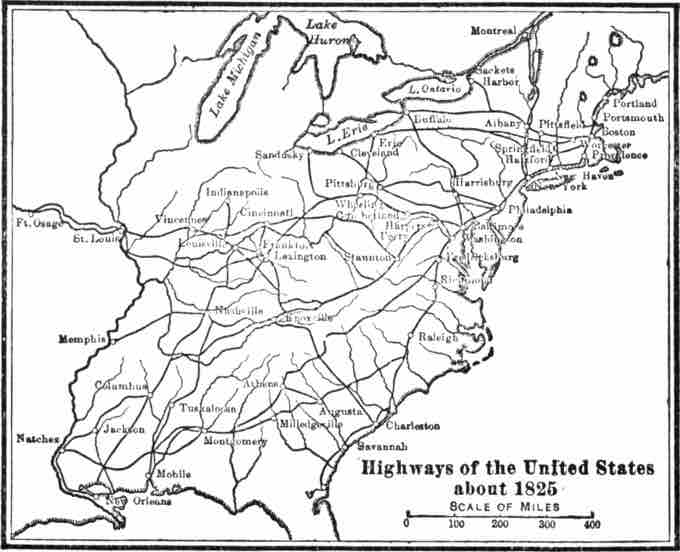

Highways of the United States, ca. 1825

Turnpikes, canals, and rail lines drastically changed America's landscape, beginning in the 1800s.

Following the War of 1812, the American economy was altered from an economy partly dependent on imports from Europe to an empire of internal commerce. With a new generation of leaders, the Republican Party came to embrace the principles of government activism and the development of large-scale domestic manufacturing.

Westward invasion into American Indian territory relegated rich new farmlands to the United States. This period of rapid development in the East and expansion in the West produced a wave of land speculation that resulted in economic periods of boom and bust. These periods were characterized by patterns of high market prices followed by ruinously low prices, falling production, and bankruptcies by producers.