Decline of the Yuan Dynasty

The final years of the Yuan dynasty were marked by struggle, famine, and bitterness among the populace. In time, Kublai Khan's successors lost all influence on other Mongol lands across Asia, as the Mongols beyond the Middle Kingdom saw them as too Chinese. Gradually, they lost influence in China as well. The reigns of the later Yuan emperors were short and marked by intrigues and rivalries. Uninterested in administration, they were separated from both the army and the populace, and China was torn by dissension and unrest. Outlaws ravaged the country without interference from the weakening Yuan armies.

From the late 1340s onwards, people in the countryside suffered from frequent natural disasters such as droughts, floods, and the resulting famines, and the government's lack of effective policy led to a loss of popular support. In 1351, the Red Turban Rebellion started and grew into a nationwide uprising. In 1354, when Toghtogha led a large army to crush the Red Turban rebels, Toghun Temür suddenly dismissed him for fear of betrayal. This resulted in Toghun Temür's restoration of power on the one hand and a rapid weakening of the central government on the other. He had no choice but to rely on local warlords' military power, and gradually lost his interest in politics and ceased to intervene in political struggles, all of which led to the official end of the Yuan dynasty in China. After trying to regain Khanbaliq, an effort that failed, he died in Yingchang (located in present-day Inner Mongolia) in 1370. Yingchang was seized by the Ming shortly after his death. Some Yuan royal family members still live in Henan today.

Prince Basalawarmi of Liang established a separate pocket of resistance to the Ming in Yunnan and Guizhou, but his forces were decisively defeated by the Ming in 1381. By 1387 the remaining Yuan forces in Manchuria under Naghachu had also surrendered to the Ming dynasty.

Northern Yuan

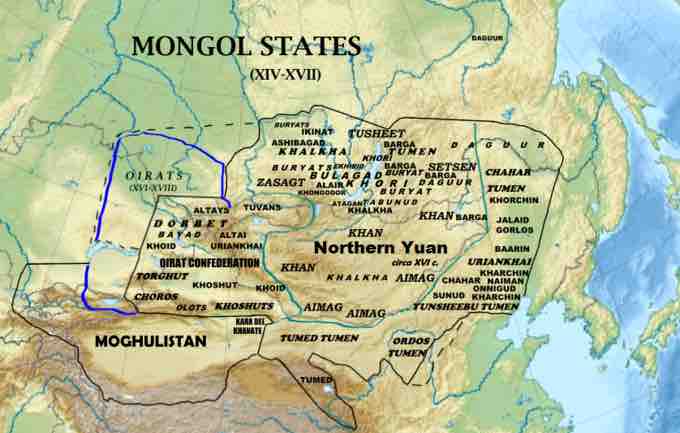

The Yuan remnants retreated to Mongolia after Yingchang fell to the Ming in 1370, and there formally carried on the name Great Yuan in what is known as the Northern Yuan dynasty. According to Chinese political orthodoxy, there could be only one legitimate dynasty whose rulers were blessed by Heaven to rule as emperors of China, and so the Ming and the Northern Yuan denied each other's legitimacy as emperors of China, although the Ming did consider the previous Yuan it had succeeded to have been a legitimate dynasty. Historians generally regard Ming dynasty rulers as the legitimate emperors of China after the Yuan dynasty.

The Ming army pursued the ex-Yuan Mongol forces into Mongolia in 1372, but were defeated by the Mongol forces under Biligtü Khan Ayushiridara and his general Köke Temür. They tried again in 1380, ultimately winning a decisive victory over the Northern Yuan in 1388. About 70,000 Mongols were taken prisoner, and Karakorum (the Northern Yuan capital) was sacked. Eight years later, the Northern Yuan throne was taken over by Biligtü Khan Ayushiridara, a descendant of Ariq Böke, instead of the descendants of Kublai Khan. The following centuries saw a succession of Genghisid rulers, many of whom were mere figureheads put on the throne by those warlords who happened to be the most powerful. Periods of conflict with the Ming dynasty intermingled with periods of peaceful relations with border trade.

Northern Yuan

The Northern Yuan at its greatest territorial extent.