INTRODUCTION: MONTESQUIEU

Baron de Montesquieu, usually referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French lawyer, man of letters, and one of the most influential political philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment. He was born in France in 1689. After losing both parents at an early age, he became a ward of his uncle, the Baron de Montesquieu. He became a counselor of the Bordeaux Parliament in 1714. A year later, he married Jeanne de Lartigue, a Protestant, who bore him three children. Montesquieu's early life occurred at a time of significant governmental change. England had declared itself a constitutional monarchy in the wake of its Glorious Revolution (1688–89) and had joined with Scotland in the Union of 1707 to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. In France the long-reigning Louis XIV died in 1715 and was succeeded by the five-year-old Louis XV. These national transformations had a great impact on Montesquieu, who would refer to them repeatedly in his work. Montesquieu withdrew from the practice of law to devote himself to study and writing.

Besides writing works on society and politics, Montesquieu traveled for a number of years through Europe including Austria and Hungary, spending a year in Italy and 18 months in England where he became a freemason before resettling in France. He was troubled by poor eyesight and was completely blind by the time he died from a high fever in 1755.

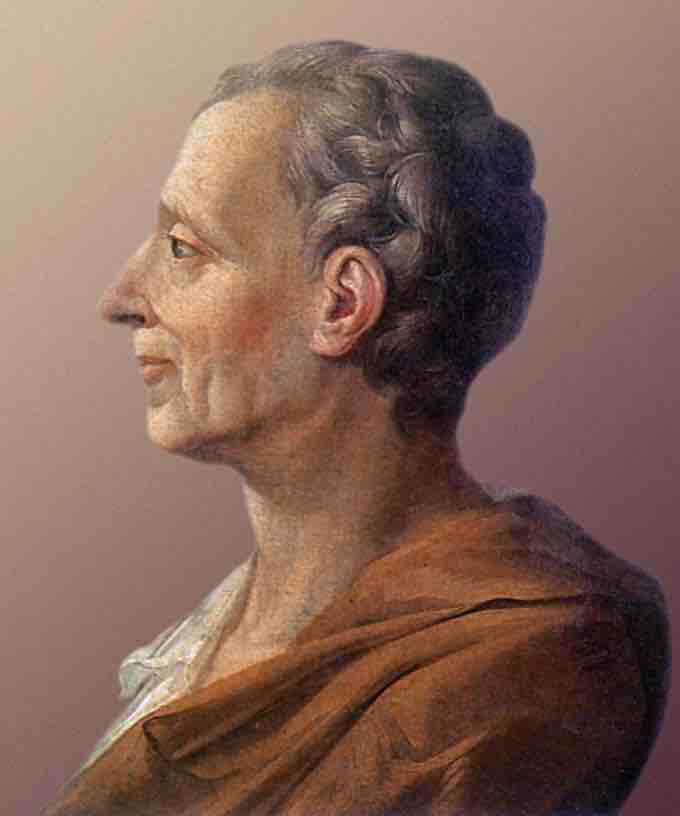

Montesquieu, portrait by an unknown artist, ca. 1727.

Montesquieu is famous for his articulation of the theory of separation of powers, which is implemented in many constitutions throughout the world. He is also known for doing more than any other author to secure the place of the word despotism in the political lexicon.

THE SPIRIT OF LAWS

The Spirit of the Laws is a treatise on political theory first published anonymously by Montesquieu in 1748. The book was originally published anonymously partly because Montesquieu's works were subject to censorship but its influence outside France grew with rapid translation into other languages. In 1750, Thomas Nugent published the first English translation. In 1751, the Catholic Church added it to its Index Librorum Prohibitorum (List of prohibited books). Yet Montesquieu's political treatise had an enormous influence on the work of many others, most notably the Founding Fathers of the United States Constitution and Alexis de Tocqueville, who applied Montesquieu's methods to a study of American society in Democracy in America.

Montesquieu spent around twenty one years researching and writing The Spirit of the Laws, covering many things like the law, social life, and the study of anthropology and providing more than 3,000 commendations. In this political treatise, Montesquieu pleaded in favor of a constitutional system of government and the separation of powers, the ending of slavery, the preservation of civil liberties and the law, and the idea that political institutions ought to reflect the social and geographical aspects of each community.

Montesquieu defines three main political systems: republican, monarchical, and despotic. As he defines them, republican political systems vary depending on how broadly they extend citizenship rights—those that extend citizenship relatively broadly are termed democratic republics, while those that restrict citizenship more narrowly are termed aristocratic republics. The distinction between monarchy and despotism hinges on whether or not a fixed set of laws exists that can restrain the authority of the ruler. If so, the regime counts as a monarchy. If not, it counts as despotism.

A second major theme in The Spirit of Laws concerns political liberty and the best means of preserving it. Montesquieu's political liberty is what we might call today personal security, especially insofar as this is provided for through a system of dependable and moderate laws. He distinguishes this view of liberty from two other, misleading views of political liberty. The first is the view that liberty consists in collective self-government—i.e. that liberty and democracy are the same. The second is the view that liberty consists in being able to do whatever one wants without constraint. Political liberty is not possible in a despotic political system, but it is possible, though not guaranteed, in republics and monarchies. Generally speaking, establishing political liberty requires two things: the separation of the powers of government and the appropriate framing of civil and criminal laws so as to ensure personal security.

SEPARATION OF POWERS AND APPROPRIATE LAWS

Building on and revising a discussion in John Locke's Second Treatise of Government, Montesquieu argues that the executive, legislative, and judicial functions of government (the so-called tripartite system) should be assigned to different bodies, so that attempts by one branch of government to infringe on political liberty might be restrained by the other branches (checks and balances). Montesquieu based this model on the Constitution of the Roman Republic and the British constitutional system. He took the view that the Roman Republic had powers separated so that no one could usurp complete power. In the British constitutional system, Montesquieu discerned a separation of powers among the monarch, Parliament, and the courts of law. He also notes that liberty cannot be secure where there is no separation of powers, even in a republic. Montesquieu also intends what modern legal scholars might call the rights to "robust procedural due process," including the right to a fair trial, the presumption of innocence, and the proportionality in the severity of punishment. Pursuant to this requirement to frame civil and criminal laws appropriately to ensure political liberty. Finally, Montesquieu also argues against slavery and for the freedom of thought, speech, and assembly.