JOHN LOCKE: INTRODUCTION

John Locke was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "Father of Liberalism." Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, he is equally important to social contract theory. His work greatly affected the development of epistemology and political philosophy. His writings influenced Voltaire and Rousseau, many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well as the American revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the United States Declaration of Independence.

Locke was born in 1632 in Wrington, Somerset, about 12 miles from Bristol and grew up in the nearby town of Pensford. In 1647, he was sent to the prestigious Westminster School in London and after completing studies there, he was admitted to Christ Church, Oxford in 1652. Although a capable student, Locke was irritated by the undergraduate curriculum of the time. He found the works of modern philosophers, such as René Descartes, more interesting than the classical material taught at the university. Through a friend, Locke was introduced to medicine and the experimental philosophy being pursued at other universities and in the Royal Society, of which he eventually became a member. In 1667, he moved to London to serve as a personal physician and where he resumed his medical studies. He also served as Secretary of the Board of Trade and Plantations and Secretary to the Lords Proprietor of Carolina, which helped to shape his ideas on international trade and economics. Locke fled to the Netherlands in 1683, under strong suspicion of involvement in the Rye House Plot, although there is little evidence to suggest that he was directly involved in the scheme. In the Netherlands, he had time to return to his writing although the bulk of Locke's publishing took place upon his return from exile in 1688. He died in 1704. Locke never married nor had children.

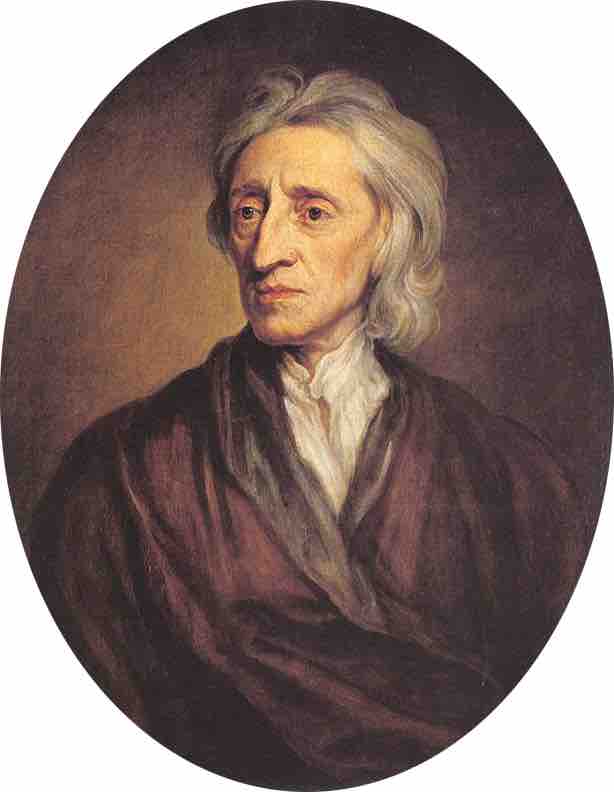

Portrait of John Locke, by Sir Godfrey Kneller,1697, State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Locke's theory of mind has been as influential as his political theory and is often cited as the origin of modern conceptions of identity and the self. Locke was the first to define the self through a continuity of consciousness. He postulated that, at birth, the mind was a blank slate or tabula rasa. Contrary to Cartesian philosophy based on pre-existing concepts, he maintained that we are born without innate ideas and that knowledge is instead determined only by experience derived from sense perceptions.

TWO TREATISES OF GOVERNMENT

Two Treatises of Government, Locke's most important and influential work on political theory, was first published anonymously in 1689. It is divided into the First Treatise and the Second Treatise. The First Treatise is focused on the refutation of Sir Robert Filmer, in particular his Patriarcha, which argued that civil society was founded on a divinely sanctioned patriarchalism. Locke proceeds through Filmer's arguments, contesting his proofs from Scripture and ridiculing them as senseless, until concluding that no government can be justified by an appeal to the divine right of kings. The Second Treatise outlines a theory of civil society. Locke begins by describing the state of nature, a picture much more stable than Thomas Hobbes' state of "war of every man against every man," and argues that all men are created equal in the state of nature by God. He goes on to explain the hypothetical rise of property and civilization, in the process explaining that the only legitimate governments are those that have the consent of the people. Therefore, any government that rules without the consent of the people can, in theory, be overthrown.

Locke's political theory was founded on social contract theory. Unlike Hobbes, Locke believed that human nature is characterized by reason and tolerance. Similarly to Hobbes, he assumed that the sole right to defend in the state of nature was not enough, so people established a civil society to resolve conflicts in a civil way with help from government in a state of society. However, Locke never refers to Hobbes by name and may instead have been responding to other writers of the day. He also advocated governmental separation of powers and believed that revolution is not only a right but an obligation in some circumstances. These ideas would come to have profound influence on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. However, Locke did not demand a republic. Rather, he believed a legitimate contract could easily exist between citizens and a monarchy, an oligarchy, or in some mixed form.

NATURAL RIGHTS

Locke's conception of natural rights is captured in his best known statement that individuals have a right to protect their "life, health, liberty, or possessions" and in his belief that the natural right to property is derived from labor. He defines the state of nature as a condition, in which humans are rational and follow natural law and in which all men are born equal with the right to life, liberty and property. However, when one citizen breaks the Law of Nature, both the transgressor and the victim enter into a state of war, from which it is virtually impossible to break free. Therefore, Locke argued that individuals enter into civil society to protect their natural rights via an "unbiased judge" or common authority, such as courts.

CONSTITUTION OF CAROLINA AND VIEWS ON SLAVERY

Locke's writings have often been tied to liberalism, democracy, and the foundation of the United States as the first modern democratic republic. However, historians also note that Locke was a major investor in the English slave-trade through the Royal African Company. In addition, he participated in drafting the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which established a feudal aristocracy and gave a master absolute power over his slaves. Because of his opposition to aristocracy and slavery in his major writings, some historians accuse Locke of hypocrisy and racism and point out that his idea of liberty is reserved to Europeans or even the European capitalist class only. The debate over the disparities between Locke's philosophical arguments and his personal involvement in the slave trade and slavery in North American colonies and over whether his writings provide, in fact, justification of slavery continues among scholars.