In the Late Middle Ages (1340–1400) Europe experienced the most deadly disease outbreak in history when the Black Death, the infamous pandemic of bubonic plague, hit in 1347. The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 75–200 million people and peaking in Europe in the years 1348–1350.

Path of the Black Death to Europe

The Black Death is thought to have originated in the arid plains of Central Asia, where it then travelled along the Silk Road, reaching the Crimea by 1346. It was most likely carried by Oriental rat fleas living on the black rats that were regular passengers on merchant ships.

Mongol dominance of Eurasian trade routes enabled safe passage through more secured trade routes. Goods were not the only thing being traded; disease also was passed between cultures. From Central Asia the Black Death was carried east and west along the Silk Road by Mongol armies and traders making use of the opportunities of free passage within the Mongol Empire offered by the Pax Mongolica. The epidemic began in Europe with an attack that Mongols launched on the Italian merchants' last trading station in the region, Caffa in the Crimea. In the autumn of 1346, plague broke out among the besiegers and then penetrated into the town. When spring arrived, the Italian merchants fled on their ships, unknowingly carrying the Black Death. The plague initially spread to humans near the Black Sea and then outwards to the rest of Europe as a result of people fleeing from one area to another.

The spread of the Black Death

Animation showing the spread of The Black Death from Central Asia to East Asia and Europe from 1346 to 1351.

Spreading throughout the Mediterranean and Europe, the Black Death is estimated to have killed 30–60% of Europe's total population. While Europe was devastated by the disease, the rest of the world fared much better. In India, populations rose from 91 million in 1300, to 97 million in 1400, to 105 million in 1500. Sub-Saharan Africa also remained largely unaffected by the plagues.

Symptoms and Treatment

The most infamous symptom of bubonic plague is an infection of the lymph glands, which become swollen and painful and are known as buboes. Buboes associated with the bubonic plague are commonly found in the armpits, groin, and neck region. Gangrene of the fingers, toes, lips, and nose is another common symptom.

Medieval doctors thought the plague was created by air corrupted by humid weather, decaying unburied bodies, and fumes produced by poor sanitation. The recommended treatment for the plague was a good diet, rest, and relocating to a non-infected environment so the individual could get access to clean air. This did help, but not for the reasons the doctors of the time thought. In actuality, because they recommended moving away from unsanitary conditions, people were, in effect, getting away from the rodents that harbored the fleas carrying the infection.

Plague doctors advised walking around with flowers in or around the nose to "ward off the stench and perhaps the evil that afflicted them." Some doctors wore a beak-like mask filled with aromatic items. The masks were designed to protect them from putrid air, which was seen as the cause of infection.

A plague doctor

Drawing illustrating the clothes and "beak" of a plague doctor.

Since people didn't have the knowledge to understand the plague, people believed it was a punishment from God. The thought the only way to be rid of the plague was to be forgiven by God. One method was to carve the symbol of the cross onto the front door of a house with the words "Lord have mercy on us" near it.

Impact of the Black Death on Society and Culture

The aftermath of the plague created a series of religious, social, and economic upheavals, which had profound effects on the course of European history. It took 150 years for Europe's population to recover, and the effects of the plague irrevocably changed the social structure, resulting in widespread persecution of minorities such as Jews, foreigners, beggars, and lepers. The uncertainty of daily survival has been seen as creating a general mood of morbidity, influencing people to "live for the moment."

Because 14th-century healers were at a loss to explain the cause of the plague, Europeans turned to astrological forces, earthquakes, and the poisoning of wells by Jews as possible reasons for the plague's emergence. No one in the 14th century considered rat control a way to ward off the plague, and people began to believe only God's anger could produce such horrific displays. Giovanni Boccaccio, an Italian writer and poet of the 14th century, questioned whether plague was sent by God for human's correction, or if it came through the influence of the heavenly bodies. Christians accused Jews of poisoning public water supplies in an effort to ruin European civilization. The spreading of this rumor led to complete destruction of entire Jewish towns, but it was caused simply by suspicion on the part of the Christians, who noticed that the Jews had lost fewer lives in the Plague due to their hygienic practices. In February 1349, 2,000 Jews were murdered in Strasbourg. In August of the same year, the Jewish communities of Mainz and Cologne were exterminated.

There was a significant impact on religion, as many believed the plague was God's punishment for sinful ways. Church lands and buildings were unaffected, but there were too few priests left to maintain the old schedule of services. Over half the parish priests, who gave the final sacraments to the dying, died themselves. The church moved to recruit replacements, but the process took time. New colleges were opened at established universities, and the training process sped up. The shortage of priests opened new opportunities for lay women to assume more extensive and important service roles in local parishes.

Flagellantism was a 13th and 14th centuries movement involving radicals in the Catholic Church. It began as a militant pilgrimage and was later condemned by the Catholic Church as heretical. The peak of the activity was during the Black Death. Flagellant groups spontaneously arose across Northern and Central Europe in 1349, except in England. The German and Low Countries movement, the Brothers of the Cross, is particularly well documented. They established their camps in fields near towns and held their rituals twice a day. The followers would fall to their knees and scourge themselves, gesturing with their free hands to indicate their sin and striking themselves rhythmically to songs, known as Geisslerlieder, until blood flowed. Sometimes the blood was soaked up by rags and treated as a holy relic. Some towns began to notice that sometimes Flagellants brought plague to towns where it had not yet surfaced. Therefore, later they were denied entry. The flagellants responded with increased physical penance.

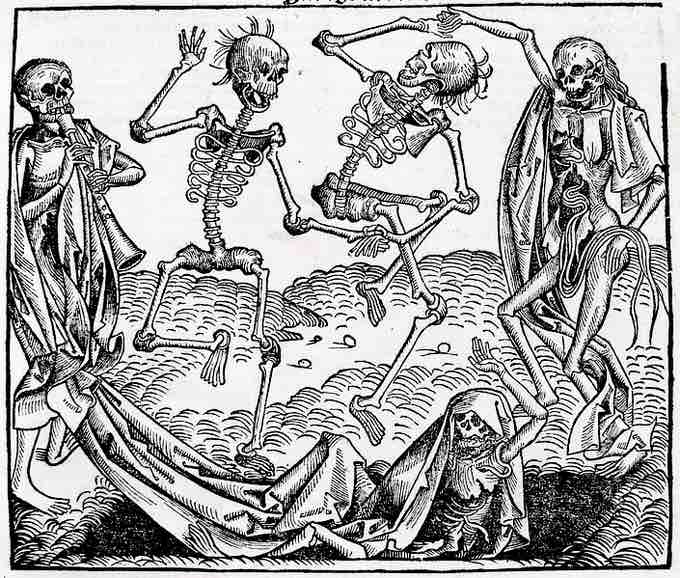

The Black Death had a profound impact on art and literature. After 1350, European culture in general turned very morbid. The common mood was one of pessimism, and contemporary art turned dark with representations of death. La Danse Macabre, or the dance of death, was a contemporary allegory, expressed as art, drama, and printed work. Its theme was the universality of death, expressing the common wisdom of the time that no matter one's station in life, the dance of death united all. It consisted of the personified Death leading a row of dancing figures from all walks of life to the grave—typically with an emperor, king, pope, monk, youngster, and beautiful girl, all in skeleton-state. Such works of art were produced under the impact of the Black Death, reminding people of how fragile their lives and how vain the glories of earthly life were.

Danse Macabre

The Dance of Death (1493) by Michael Wolgemut, from the Liber chronicarum by Hartmann Schedel.

Economic Impact of the Plague

The great population loss wrought by the plague brought favorable results to the surviving peasants in England and Western Europe. There was increased social mobility, as depopulation further eroded the peasants' already weakened obligations to remain on their traditional holdings. Feudalism never recovered. Land was plentiful, wages high, and serfdom had all but disappeared. It was possible to move about and rise higher in life.

The Black Death encouraged innovation of labor-saving technologies, leading to higher productivity. There was a shift from grain farming to animal husbandry. Grain farming was very labor-intensive, but animal husbandry needed only a shepherd, a few dogs, and pastureland.

Since the plague left vast areas of farmland untended, they were made available for pasture and thus put more meat on the market; the consumption of meat and dairy products went up, as did the export of beef and butter from the Low Countries, Scandinavia, and northern Germany. However, the upper classes often attempted to stop these changes, initially in Western Europe, and more forcefully and successfully in Eastern Europe, by instituting sumptuary laws. These regulated what people (particularly of the peasant class) could wear so that nobles could ensure that peasants did not begin to dress and act as higher class members with their increased wealth. Another tactic was to fix prices and wages so that peasants could not demand more with increasing value. In England, the Statute of Labourers of 1351 was enforced, meaning no peasant could ask for more wages than they had in 1346. This was met with varying success depending on the amount of rebellion it inspired; such a law was one of the causes of the 1381 Peasants' Revolt in England.

Plague brought an eventual end of serfdom in Western Europe. The manorial system was already in trouble, but the Black Death assured its demise throughout much of Western and Central Europe by 1500. Severe depopulation and migration of people from village to cities caused an acute shortage of agricultural laborers. In England, more than 1300 villages were deserted between 1350 and 1500.