The Crusades were a series of military conflicts conducted by Christian knights for the defense of Christians and for the expansion of Christian domains between the 11th and 15th centuries. Generally, the Crusades refer to the campaigns in the Holy Land sponsored by the papacy against Muslim forces. There were other crusades against Islamic forces in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily, as well as campaigns of Teutonic knights against pagan strongholds in Eastern Europe. A few crusades, such as the Fourth Crusade, were waged within Christendom against groups that were considered heretical and schismatic. Crusades were fought for many reasons—to capture Jerusalem, recapture Christian territory, or defend Christians in non-Christian lands; as a means of conflict resolution among Roman Catholics; for political or territorial advantage; and to combat paganism and heresy.

Origin of the Crusades

The origin of the Crusades in general, and particularly of the First Crusade, is widely debated among historians. The confusion is partially due to the numerous armies in the First Crusade, and their lack of direct unity. The similar ideologies held the armies to similar goals, but the connections were rarely strong, and unity broke down often. The Crusades are most commonly linked to the political and social situation in 11th-century Europe, the rise of a reform movement within the papacy, and the political and religious confrontation of Christianity and Islam in Europe and the Middle East. Christianity had spread throughout Europe, Africa, and the Middle East in Late Antiquity, but by the early 8th century Christian rule had become limited to Europe and Anatolia after the Muslim conquests.

Background in Europe

The Holy Land had been part of the Roman Empire, and thus the Byzantine Empire, until the Islamic conquests. In the 7th and 8th centuries, Islam was introduced in the Arabian Peninsula by the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his followers. This formed a unified Muslim polity, which led to a rapid expansion of Arab power, the influence of which stretched from the northwest Indian subcontinent, across Central Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, southern Italy, and the Iberian Peninsula, to the Pyrenees. Tolerance, trade, and political relationships between the Arabs and the Christian states of Europe waxed and waned. For example, the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah destroyed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but his successor allowed the Byzantine Empire to rebuild it. Pilgrimages by Catholics to sacred sites were permitted, resident Christians were given certain legal rights and protections under Dhimmi status, and interfaith marriages were not uncommon. Cultures and creeds coexisted and competed, but the frontier conditions became increasingly inhospitable to Catholic pilgrims and merchants.

At the western edge of Europe and of Islamic expansion, the Reconquista (recapture of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims) was well underway by the 11th century, reaching its turning point in 1085 when Alfonso VI of León and Castile retook Toledo from Muslim rule. Increasingly in the 11th century, foreign knights, mostly from France, visited Iberia to assist the Christians in their efforts.

The heart of Western Europe had been stabilized after the Christianization of the Saxon, Viking, and Hungarian peoples by the end of the 10th century. However, the breakdown of the Carolingian Empire gave rise to an entire class of warriors who now had little to do but fight among themselves. The random violence of the knightly class was regularly condemned by the church, and so it established the Peace and Truce of God to prohibit fighting on certain days of the year.

At the same time, the reform-minded papacy came into conflict with the Holy Roman Emperors, resulting in the Investiture Controversy. The papacy began to assert its independence from secular rulers, marshaling arguments for the proper use of armed force by Catholics. Popes such as Gregory VII justified the subsequent warfare against the emperor's partisans in theological terms. It became acceptable for the pope to utilize knights in the name of Christendom, not only against political enemies of the papacy, but also against Al-Andalus, or, theoretically, against the Seljuq dynasty in the east. The result was intense piety, an interest in religious affairs, and religious propaganda advocating a just war to reclaim Palestine from the Muslims. Participation in such a war was seen as a form of penance that could counterbalance sin.

Aid to Byzantium

To the east of Europe lay the Byzantine Empire, composed of Christians who had long followed a separate Orthodox rite; the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches had been in schism since 1054. Historians have argued that the desire to impose Roman church authority in the east may have been one of the goals of the Crusades, although Urban II, who launched the First Crusade, never refers to such a goal in his letters on crusading. The Seljuq Empire had taken over almost all of Anatolia after the Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071; however, their conquests were piecemeal and led by semi-independent warlords, rather than by the sultan. A dramatic collapse of the empire's position on the eve of the Council of Clermont brought Byzantium to the brink of disaster. By the mid-1090s, the Byzantine Empire was largely confined to Balkan Europe and the northwestern fringe of Anatolia, and faced Norman enemies in the west as well as Turks in the east. In response to the defeat at Manzikert and subsequent Byzantine losses in Anatolia in 1074, Pope Gregory VII had called for the milites Christi ("soldiers of Christ") to go to Byzantium's aid.

Seljuq Empire

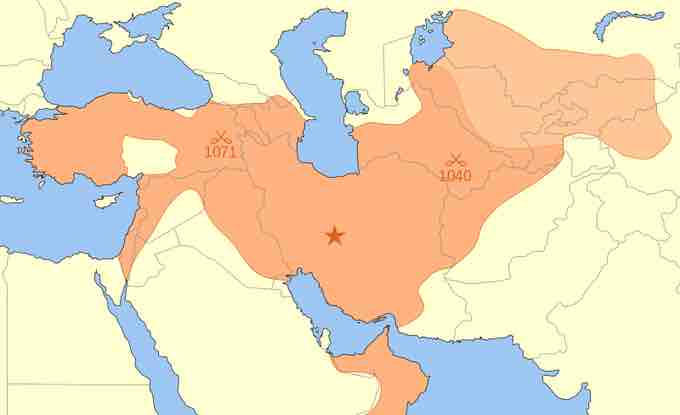

The Great Seljuq Empire at its greatest extent (1092).

While the Crusades had causes deeply rooted in the social and political situations of 11th-century Europe, the event actually triggering the First Crusade was a request for assistance from Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Alexios was worried about the advances of the Seljuqs, who had reached as far west as Nicaea, not far from Constantinople. In March 1095, Alexios sent envoys to the Council of Piacenza to ask Pope Urban II for aid against the Turks.

Urban responded favorably, perhaps hoping to heal the Great Schism of forty years earlier, and to reunite the Church under papal primacy by helping the eastern churches in their time of need. Alexios and Urban had previously been in close contact in 1089 and later, and had openly discussed the prospect of the (re)union of the Christian church. There were signs of considerable co-operation between Rome and Constantinople in the years immediately before the Crusade.

In July 1095, Urban turned to his homeland of France to recruit men for the expedition. His travels there culminated in the Council of Clermont in November, where, according to the various speeches attributed to him, he gave an impassioned sermon to a large audience of French nobles and clergy, graphically detailing the fantastical atrocities being committed against pilgrims and eastern Christians. Urban talked about the violence of European society and the necessity of maintaining the Peace of God; about helping the Greeks, who had asked for assistance; about the crimes being committed against Christians in the east; and about a new kind of war, an armed pilgrimage, and of rewards in heaven, where remission of sins was offered to any who might die in the undertaking. Combining the idea of pilgrimage to the Holy Land with that of waging a holy war against infidels, Urban received an enthusiastic response to his speeches and soon after began collecting military forces to begin the First Crusade.

Council of Clermont

Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont, where he gave speeches in favor of a Crusade.