Good writing is essentially rewriting. I am positive of this. —Roald Dahl

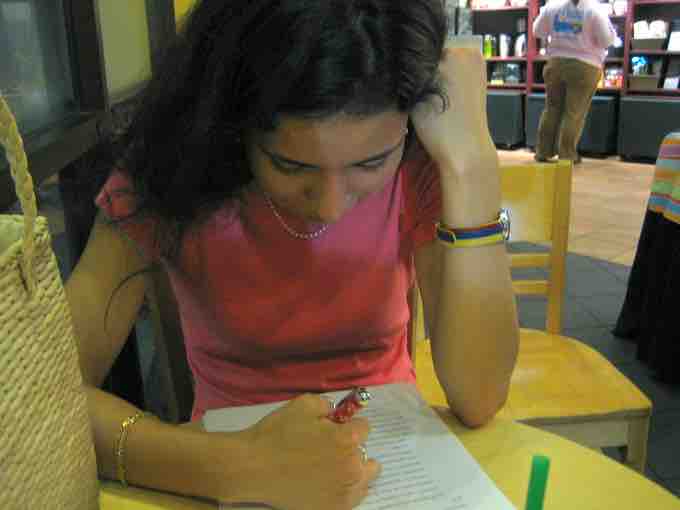

One of the best tools in a writer's toolkit is the ability to revise. As with the prior stages of writing, it's actually not a distinct phase that happens only once, but part of a recursive process. Drafting and revising is a dialogue between the inner artist and the inner critic. The artist should not be bothered by the critic while in the creative zone, and the critic should be let loose unfettered during the revision process.

Writing and rewriting are a constant search for what it is one is saying. —John Updike

Revision is almost universally reviled initially, but the more experienced a writer becomes, the more he or she appreciates this pruning process. Revising tightens the argument, strengthens the voice, and smoothes the syntax so you're left with only the best bits.

In the prewriting stage, we ask the inner critic to take a nice long nap all the way through the first drafting phase, but now we awaken it and put it to work.

Revision

Revising ideas so that they are persuasive, cogent, and form a solid argument is the real work of writing.

When Should I Revise My Paper?

Revision begins after you've finished your first draft and is repeated as often as necessary from that stage forward. It's useful, though, to take at least a day and a night away from the draft, rather than jumping into revising immediately. The break will give you the necessary distance from what you have written to look at it with a critical eye and will give you the psychological space to shift from artist to critic.

Reviewing

Re-reading completed work is essential for more than just catching typos.

How Should I Get Started?

We first need to distinguish revising from editing. You're going to have a separate round of going through your paper to fix grammar mistakes, adjust vocabulary, and make sure you have not repeated the word "very" too many times. There's no need to think about that stage now. What we're doing here is looking at how your argument is constructed.

The kinds of changes you make when revising relate to how well you're making your case. You may have to alter how your argument works or how it's organized. Changes at this level are the biggest ones you will make, which is why there's no point in playing around with word choice or punctuation when you might be rewriting, or even deleting, the entire paragraph.

The first thing to look for when revising is purpose. Now that you've written the whole paper, look back at your thesis statement. Is it still what the paper is about? And if so, does everything in your paper relate back to that argument? Read through the paper now and check for purpose.

The next step is to ensure that your argument makes sense and has power. All of your claims may relate to your thesis, yes, but are you convinced? Remember, you're wearing your critic hat now. Pretend you didn't write the paper and are being paid as a critic. Make yourself very hard to please. Then go through the paper and make notes on these aspects and any others that strike you as you read.

The following are specific categories of things to watch for.

Argumentation

- Is the thesis set up in a way that makes you care about it?

- Are the claims related precisely to the thesis, or do they become tangential at any point? Are they interesting?

- Does the evidence prove what it is intended to prove?

- Are there well-placed examples? Are they entirely relevant?

- By the end of the paper, might someone who believed differently from the thesis be swayed by the argument? If not, why not? What's missing? And if so, what were the strongest points?

- Are there extraneous paragraphs or sentences that seem less important to the point?

- Where is the climax of this paper, where you most feel the author's mastery?

Organization

- Is the structure of the paper as effective as it can be?

- Does the order of the paragraphs make sense?

- Does each paragraph build off of what was developed in the previous one?

- Does the end of the paper relate back to the beginning?

- Are the different steps of the argument linked in a logical manner?

- Is every step adequately explained, or are there leaps or holes in logic?

- Do some ideas seem to come out of nowhere, or do you feel like you've been prepared for each new concept?

Voice and Consistency

- Does the topic capture your interest because of the way it's presented?

- Can you tell from the tone that the author cares about the topic?

- Is the author's tone maintained throughout the paper?

- Does everything in this paper work towards articulating or proving the thesis?

What to Do With Your Critique

Another reason students avoid revising is because they jump too quickly from the critique part of revision to the rewrite, asking the brain to do a creative activity when it's still in the critical mindset.

So, if you have the time, it would be wise to take a break from the paper again at this point, at least for a little while. Once you've heard from the critic, taking a rest will give your brain time to relax and come up with ideas for revisions, moving naturally back into inspired, creative mode.

When you've taken that time, the process may flow quite naturally. If not, though, recognize that you're repeating the steps you used in drafting.

Address Foundational Issues

First, you shore up the thesis statement (or rewrite it entirely), then address the claims—rewriting them for clarity or deleting them if they're not strong. You can even go back to your outline and move things around again, reevaluating the order of the argument. Thesis, claims, order: these are the bones of the paper—the foundation. Only after you're satisfied with these do you move to revising paragraphs.

Breaking Down the Big Picture: Revising at the Paragraph Level

For each paragraph and section, ask yourself two things:

- What do you want each paragraph to do?

- How well does each paragraph complete that task?

We begin with the body of the paper, leaving the introduction and conclusion for later. The body is the meat on the bones. It needs to be evenly distributed and form a powerful whole. For each one, ask the following questions, but ask them in gentler artist mode, rather than in ruthless critic mode:

- Is this paragraph necessary to the argument?

- Is every sentence relevant to the claim made in the paragraph?

- Is there anything missing from the first sentence to the claim—a piece of evidence or an argument that would make it more convincing?

- Is the argument fully explained?

- Does it flow well?

- How does each sentence make you feel? What is the trajectory of your feeling from sentence to sentence to claim?

- Does the information in this paragraph logically lead to the next one?

- Is the transition to the next paragraph smooth and easy to follow?

Fix these things now.

The introduction and conclusion bring in more of the artistic aspects of writing, and so you'll want to relax the critic a bit here and look at these paragraphs from an interested reader's perspective. Again, not a bad idea to take a break before addressing these two paragraphs.

Ask these questions for the introduction:

- Do the first few sentences intrigue me?

- Does the subject seem compelling?

- Does my attention lapse at any point?

- Does the narrative lead me to an understanding of the topic?

- How do I feel after reading it? Energized? Eager for more?

Take time to revise the introduction now, but consider beginning the revision with a prewriting exercise to get the creative juices flowing again.

Ask the following questions about your concluding paragraph:

- Is the argument woven together here or simply restated?

- Does this paragraph introduce new evidence or claims?

- Do I feel a sense of completion and satisfaction when I finish, or am I left with unanswered questions and unmet expectations?

- Is there a sense of artistry, of mastery, to this last paragraph or set of paragraphs?

If you can leave the revision of the conclusion for a few hours after answering these questions, your brain may solve any question of how to skillfully weave your argument together. Allow yourself some quiet time to let images and stories to arise. Re-read the revised introduction as a source of inspiration.

Letting Go

Revising can be a metaphorical journey in letting go. It's easy to get attached to what we've written, and deleting something you've spent hours on can feel painful. Yes, you know it will make for a better paper in the long run, but you may bemoan all the lost time and effort.

If you can reframe it for yourself, though, and recognize that revising is not separate from writing but an integral and vital part of the process, you'll see that the next paragraph you write is built on the one you just had to delete. Your final paper will be successful because you trusted the process—trusted your creative mind to come up with new material even better than the old.

That's the magic of revisions—every cut is necessary and every cut hurts, but something new always grows. —Kelly Barnhill