You may have heard that data is huge — changing the way science is done, enabling new kinds of consumer and business applications, furthering citizen involvement and government transparency, spawning a new class of software for processing big data and new interdisciplinary class of “data scientists” to help utilize all this data — not to mention metadata (data about data), linked data and the semantic web — there’s a whole lot of data, there’s more every day, and it’s potentially extremely valuable.

Much of the potential value of data is to society at large — more data has the potential to facilitate enhanced scientific collaboration and reproducibility, more efficient markets, increased government and corporate transparency, and overall to speed discovery and understanding of solutions to planetary and societal needs.

A big part of the potential value of data, in particular its society-wide value, is realized by use across organizational boundaries. How does this occur (legally)? Facts themselves are not covered by copyright and related restrictions, though the extent to which this is the case (e.g., for compilations of facts) varies considerably across jurisdictions. Many sites give narrow permission to use data via terms of service. Much ad hoc data sharing occurs among researchers. And increasingly, open data is facilitated by sharing under public terms, e.g. CC licenses or the CC0 public domain dedication.

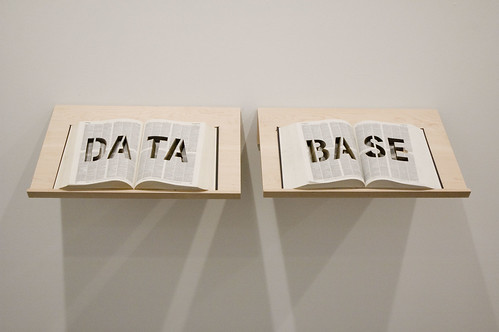

CC tools, data, and databases

Since soon after the release of version 1.0 of the CC license suite (December, 2002) people have published data and databases under CC licenses. MusicBrainz is an early example (note their recognition that parts of the MusicBrainz database is strictly factual, so in the public domain, while other parts are licensible). Other examples include Freebase, DBpedia (structured information extracted from Wikipedia), OpenStreetMap, and various governments (Australia in particular has been a leader).

More recently CC0 has gained wide use for releasing data into the public domain (to the extent it isn’t already), not only in science, as expected, but also for bibliographic, social media, public sector data, and much more.

With the exception of strongly recommending CC0 (public domain) for scientific data, Creative Commons has been relatively quiet about use of our licenses for data and databases. Prior to coming to the public domain recommendation for scientific data, we published a FAQ on CC licenses and databases, which is still informative. It is important to recognize going forward that the two are complementary: one concerns what ought be done in a particular domain in line with that domain’s tradition (and public funding sources), the other what is possible with respect to CC licenses and databases.

This is/ought distinction is not out of line with CC’s general approach — to offer a range (but not an infinity) of tools to enable sharing, while encouraging use of tools that enable more sharing, in particular where institutional missions and community norms align with more sharing. For a number of reasons, now is a good time to make clear and make sure that our approach to data and databases reflects CC’s general approach rather than an exaggerated caricature:

- We occasionally encounter a misimpression that CC licenses can’t be used for data and databases, or that we don’t want CC licenses to be used for data and databases. This is largely our fault: we haven’t actively communicated about CC licenses and data since the aforementioned FAQ (until very recently), meaning our only message has been “public domain for scientific data” — leaving extrapolation to other fields to the imagination.

- Our consolidation of CC education and science “divisions” has facilitated examinations of domain-specific policies, and increased policy coherence.

- Ongoing work and discussions with CC’s global affiliate network; many CC affiliates are deeply involved in promoting open public sector information, including data.

- The existence and increasing number of users of CC licenses for data and databases (see third paragraph above).

- A sense of overwhelming competitive threat from non-open data; the main alternative to public domain is not sharing at all — absence of a strong CC presence, except for a normative one in science, creates a correspondingly large opportunity cost for society due to “failed sharing” (e.g., under custom, non-interoperable terms) and lack of sharing.

- A long-term shift in understanding of CC’s role: from CC as purveyor of a variety of tools and policies to CC as steward of the commons, and thus need to put global maximization, interoperability and standards before any single tool or policy idea that sounds good on its own, and to encourage (and sometimes push) producers of data and databases to do the same.

- We’ve thought and learned a lot about data and databases and CC’s role in open data. In 2002 data was not central to CC’s programs, now (in keeping with the times), it is.

- Ongoing confusion among providers and users of data about the copyrightability of data (it depends) and rights that may or may not exist as a result of how the data is compiled and distributed — the database.

- Later in 2011 we expect to begin a public requirements process for version 4.0 of our license suite. At the top level, we know that an absolute requirement will be to make sure the 4.0 licenses are the best possible tools (where public domain is not feasible, for whatever reason) for legally sharing data possible.

One other subtlety should be understood with respect to current (3.0) CC licenses. Data and databases are often copyrightable. When licensed under any of our licenses, the license terms apply to copyrightable data and databases, requiring adaptations that are distributed be released under the same or compatible license terms, for example, when a ShareAlike license is used.

Database rights

Databases are covered by additional rights (sometimes called “sui generis” database rights) in Europe (similar database rights exist in a few other places). A few early (2.0) European jurisdiction CC license “ports” licensed database rights along with copyright. Non-EU jurisdiction and international CC licenses have heretofore been silent on database rights. We adopted a policy that version 3.0 EU jurisdiction ports must waive license requirements and prohibitions (attribution, share-alike, etc) for uses triggering database rights — so that if the use of a database published under a CC license implicated only database rights, but not copyright, the CC license requirements and prohibitions would not apply to that use. The license requirements and prohibitions, however, continued to apply to all uses triggering copyright.

CC licenses other than EU jurisdiction 3.0 ports are silent on database rights: databases and data are licensed (i.e., subject to restrictions detailed in the license) to the extent copyrightable, and if data in the database or the database itself are not copyrightable the license restrictions do not apply to those parts (though they still apply to the remainder). Perhaps this differential handling of database rights is not ideal, given that all CC licenses (including jurisdiction ports) apply worldwide and ought be easily understandable. However, those are not the only requirements for CC tools — they are also intended to be legally valid worldwide (for which they have a good track record) and produce outcomes consistent with our mission.

These requirements mandate the caution with which we approach database rights in our license suite. In particular, database rights are widely recognized to be bad policy, and instance of a general class of additional restrictions that are harmful to the commons, and thus harmful to collaboration, innovation, participation, and the overall health of the Internet, the economy, and society.

If database rights were to be somehow “exported” to non-EU jurisdictions via CC licenses, this would be a bad outcome, contrary not only to our overall mission, but also our policy that CC licenses not effectively introduce restrictions not present by default, e.g., by attempting to make license requirements and prohibitions obviate copyright exceptions and limitations (see “public domain” and “other rights” on our deeds, and the relevant FAQ). Simply licensing database rights, just like copyright, but only to the extent they apply, just like copyright, is an option — but any option we take will be taken very carefully.

What does all this mean right now?

(1) We do recommend CC0 for scientific data — and we’re thrilled to see CC0 used in other domains, for any content and data, wherever the rights holder wants to make clear such is in the public domain worldwide, to the extent that is possible (note that CC0 includes a permissive fallback license, covering jurisdictions where relinquishment is not thought possible).

(2) However, where CC0 is not desired for whatever reason (business requirements, community wishes, institutional policy…) CC licenses can and should be used for data and databases, right now (as they have been for 8 years) — with the important caveat that CC 3.0 license conditions do not extend to “protect” a database that is otherwise uncopyrightable.

(3) We are committed to an open transparent discussion and process around making CC licenses the best possible tools for sharing data (including addressing how they handle database rights), consistent with our overall mission of maximizing the value of the commons, and cognizant of the limitations of voluntary tools such as CC’s in the context of increasingly restrictive policy and overwhelming competitive threat from non-sharing (proprietary data). This will require the expertise of our affiliates and other key stakeholders, including you — we haven’t decided anything yet and will not without taking the time and doing the research that stewards of public infrastructure perform before making changes.

(4) is a corollary of (2) and (3): use CC licenses for data and databases now, participate in the 4.0 process, and upgrade when the 4.0 suite is released, or at least do not foreclose the possibility of doing so.

Regarding discussion — please subscribe to cc-licenses for a very low volume (moderated) list, intended only for specific proposals to improve CC licenses, and announcements of versioning milestones. If you’re interested in a more active, ongoing (unmoderated) discussion, join cc-community. You might also leave a comment on this post or other means of staying in touch. We’re also taking part in a variety of other open data discussions and conferences.

By the way, what is data and what are databases?

Oh right, those questions. I won’t try to answer too seriously, for that would require legal, technical, and philosophical dissertations. All information (including software and “content”) can be thought of as data; more pertinently, data might be limited to (uncopyrightable) facts, or it may include any arrangement of information, e.g., in rows, tables, or graphs, including with (copyrightable) creativity, and creative (copyrightable) arrangements of information. Some kinds of arrangements and collections of information are characterized as databases.

Data and databases might contain what one would think of as content, e.g., prose contained in a database table. Data and databases might be contained in what one would think of as content, e.g., the structured information in Wikipedia, assertions waiting to be extracted from academic papers, and annotated content on the web, intended first for humans, but also structured for computers.

(Note that CC has been very interested in and worked toward standards for mixing content and data — apparently taking off — because such mixing is a good method for ensuring that content and data are kept accurate, in sync, and usable — for example, licensing and attribution information.)

All of this highlights the need for interoperability across “content” and “data”, which means compatible (or the same) legal tools — a good reason for ensuring that CC licenses are the best tools for data, databases and content — indeed a mandate for ensuring this is the case. Thanks in advance for your help (constructive criticism counts, as does simply using our tools — experience is the best guide) in fulfilling this mandate.

Hi,

Thanks for the enlightenment, I always thought that CC should be as clear as possible about what the licenses actually permit and what they don’t. We need explanations to trust, and it’s impossible to rely on CC movement without transparency and honesty (and I’m personally disappointed in CC about this subject).

Nevertheless, I’m not convinced by your argument:

– why don’t you speak about the OdbL? This license was created because of the lack of confidence on actual CC licenses (when applied on data). OSM changed their license from CC to ODbL: it seems like a huge process and I hope you will take it in account during your work. I think CC need to learn and to bear.

– the “droit sui generis” about DB can’t be assimilated to copyright laws: the object of this right and the prerogatives are different (because the aim is different – it’s much more like competition laws than copyright laws), so I don’t think CC licenses extend to DB as a whole (they actually only apply one the copyrightable part of these DD)

Finaly, I can’t agree to your recommendation:

“(4) is a corollary of (2) and (3): use CC licenses for data and databases now, participate in the 4.0 process, and upgrade when the 4.0 suite is released, or at least do not foreclose the possibility of doing so.”

=> thus you ask us to use CC licenses on DB, even if they actually don’t protect no copyrightable DB, to wait and rely on your next version? This solution seems to me irresponsible:

1) what happen if you finally change your mind? Who will be responsible? Creative Commons ? Or people who choose to trust CC? I’d like to recall an event quite similar with the FSF: when the first Affero GPL was wrote, the FSF claimed that because the license was compatible with the next GNU GPL v3, people can use Affero GPL without fear about the ASP loophole. However, the GNU GPL v3 finally didn’t add these term (instead an other GNU Affero GPL license was created) and all works licensed under the first Affero GPL (fortunately not too much) were available without the ASP loophole.

2) more dangerous : what is the consequence if people choose to use the DB under the last license (2, 2.5 or 3 ?)? They can extract as much data as they wish, modify these data without give anything back. I suppose the new licenses won’t appear before one or two years, why is the reason to not use better license for data (I only know the ODbL, but maybe other license exist).

BTW, I’ll try to follow the cc-licenses ML, it’s an interesting topic.

Hi Benjamin, thanks for your feedback.

* OSM has not yet changed their license to ODBL. They are in a multi-year process of doing so. We are indeed learning from this and talking to OSM.

* CC licenses extend to DB as whole to extent such falls under copyright, and with some caveats for some versions, apply only to copyrightable parts. It is certainly possible that 4.0 will extend to license sui generis consistently with copyright. This is all explained in the post, so I’m not sure what your additional point is.

* I’m also not sure what you mean by database rights being more like competition laws than copyright. Both can be characterized as incentivizing or inhibiting competition via automatic grant of rights. Feel free to explain.

* If a database is completely uncopyrightable, a CC license will do no harm. There’s a lot of uncertainty about what is copyrightable (if you look at various discussions, eg the one on LinuxWeeklyNews linked in the post) you see that much of discussion consists of conflicting assertions about what is and is not copyrightable. CC generally doesn’t take a stance on these points. Using a CC license ensures at a minimum some freedoms will be available even if copyright does apply.

* You’re wrong about AGPLv1 and GPLv3. AGPLv1 is not compatible with GPLv3. Former says “You may also choose to redistribute modified versions of this program under any version of the Free Software Foundation’s GNU General Public License version 3 or higher, so long as that version of the GNU GPL includes terms and conditions substantially equivalent to those of this license.” Which GPLv3 does not. Instead FSF published AGPLv3, and Affero published AGPLv2 as an upgrade path to AGPLv3. Nobody who released software under AGPLv1 had their software fall prey to ASP loophole as a result of FSF’s actions. I think FSF has set a good standard for license stewardship, one that CC aim to uphold, if not surpass. 🙂

* There are many data extraction and modification scenarios, some of which are covered by copyright, some by database rights (note except for EU 3.0 ports, no CC license currently even conditionally waives these), some (pure facts, whatever that might mean) by nothing at all, though as above, there’s plenty of uncertainty about what is what. The only anti-exploitation feature ODBL adds is a contractual layer, and it isn’t at all clear that it adds “protection” (because such very hard to enforce) and is probably bad policy. These are tradeoffs (and not remotely the only ones).

Look forward to your continued participation in the discussion, thanks!

Re: “OSM has not yet changed their license to ODBL. They are in a multi-year process of doing so”. OSM is requiring new users to agree to contributor terms that give OSMF ability to relicense content as OBDL. On April 1, OSM will lock out existing contributors if they do not agree to the contributor terms by them. (http://lwn.net/Articles/422493/)

Oops, sorry to reply so late …

A few points to substantiate my thoughts:

* OSM can not change its policy in « one shoot », but their will are, I guess, clearly to move to ODbL (and I think it’s a good, hard, choice) ;

* the Databases are not meant to be original, but rather to be functional: CC licenses would have therefore exceptionally effects (and more databases will be used, improved, etc.. more they will be harmonized / standardized – become non original)

* I do not understand how you can “simply” add a right (sui generis) with a so fundamental effect (not accessories as we have seen on other licenses – including GNU or CC) for people using your licenses.

* The rights of the owner of a database are very different from those of the author (on its work). So the way the license is written must also be different (in my opinion).

* Regarding the AGPL license: actually the example was effectivly irrelevant and a second version was drafted to make it compatible with the GNU AGPL only. Nevertheless, I was just arguing that promouving the use of Creative Commons licenses on the grounds that version 4 will intergrate these specificities is /so/ dangerous. Especially since I think the current licenses would be well advised to remain limited to the content – a new license can be write for databases (but OKF has already done a great job)

* I personally think that the speech should be that 1) the data is free (without any license) 2) the original data / content should be free (subject to a license CC) 3) databases should be free( ODbL type).

* Regarding ODbL (which combines IP assignment – Copyright and sui generis databases – and contract), I think its effects are quite well-controled (it also seems to me that it not extend to uses permitted by the sui generis database).

* Finaly, I think CreativeCommons’d rather work on the current database license (ODbL) to improve together their work (quite good, but I think some improvements could be done).