The Middle Ages of the European world covers approximately 1000 years of art history in Europe, and at times extends into the Middle East and North Africa. Specifically, the Early Middle Ages is generally dated from the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 CE) to approximately 1000, which marks the beginning of the Romanesque period. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional art, genres, and revivals. Art historians attempt to classify medieval art into major periods and styles, often with some difficulty, as medieval regions frequently featured distinct artistic styles, such as Anglo-Saxon art or Norse art. However, a generally accepted scheme includes Early Christian art, Migration Period art, Byzantine art, Insular art, Carolingian art, Ottonian art, Romanesque art, and Gothic art, as well as many other periods within these central aesthetic styles.

Population decline, relocations to the countryside, invasion, and movement of peoples, which had begun in Late Antiquity, continued in the Early Middle Ages. The large-scale movements of the Migration Period, including various Germanic peoples, formed new kingdoms in what remained of the Western Roman Empire. In the West, most kingdoms incorporated the few extant Roman institutions. Monasteries were founded as campaigns to Christianize pagan Europe continued. The Franks, under the Carolingian dynasty, briefly established the Carolingian Empire during the later eighth and early ninth century. It covered much of Western Europe but later succumbed to the pressures of internal civil wars combined with external invasions—Vikings from the north, Hungarians from the east, and Saracens from the south.

As literacy declined and became available only to monks and nuns who copied illuminated manuscripts, art became the primary method of communicating narratives, particularly of a Biblical nature, to the masses. The conveying of complex narratives took precedence over producing naturalistic imagery, leading to a shift toward stylized and abstracted figures for most of the early Middle Ages. Abstraction and stylization also appeared in imagery accessible only to select communities, such as monks in remote monasteries like the complex at Lindisfarne off the coast of Northumberland, England.

John the Evangelist page from the Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 635 CE)

As is common in early medieval art, the figures in this page appear flat and stylized. The bench on which John sits does not recede realistically into the space behind him. Modeling is kept to a minimum, and the clothing that John wears does not acknowledge the body beneath.

Early medieval art exists in many media. The works that remain in large numbers include sculpture, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass, metalwork, and mosaics, all of which have had a higher survival rate than fresco wall-paintings and works in precious metals or textiles such as tapestries. In the early medieval period, the "decorative arts," such as metalwork, ivory carving, and embroidery using precious metals, were probably more highly valued than paintings or sculptures. Metal and inlaid objects, such as armor and royal regalia (crowns, scepters, and the like) rank among the best known early medieval works that survive to this day.

Visigoth votive crown (before 672 CE).

Detail of a votive crown from Visigothic Spain. Gold and precious stones. Part of the Treasure of Guarrazar.

Early medieval art in Europe grew out of the artistic heritage of the Roman Empire and the iconographic traditions of the early Christian church. These sources were mixed with the vigorous "Barbarian" artistic culture of Northern Europe to produce a remarkable artistic legacy. The history of medieval art can be seen as an ongoing interplay between the elements of classical, early Christian, and "barbarian" art. Apart from the formal aspects of classicism, there was a continuous tradition of realistic depiction that survived in Byzantine art of Eastern Europe throughout the period. In the West realistic presentation appears intermittently, combining and sometimes competing with new expressionist possibilities. These expressionistic styles developed both in Western Europe and in the Northern aesthetic of energetic decorative elements.

Monks and monasteries had a deep effect on the religious and political life of the Early Middle Ages, in various cases acting as land trusts for powerful families, centers of propaganda and royal support in newly conquered regions, and bases for missions and proselytizing. They were the main and sometimes only outposts of education and literacy in a region. Many of the surviving manuscripts of the Latin classics were copied in monasteries in the Early Middle Ages. Monks were also the authors of new works, including history, theology, and other subjects, written by authors such as Bede (died 735), a native of northern England who wrote in the late seventh and early eighth centuries.

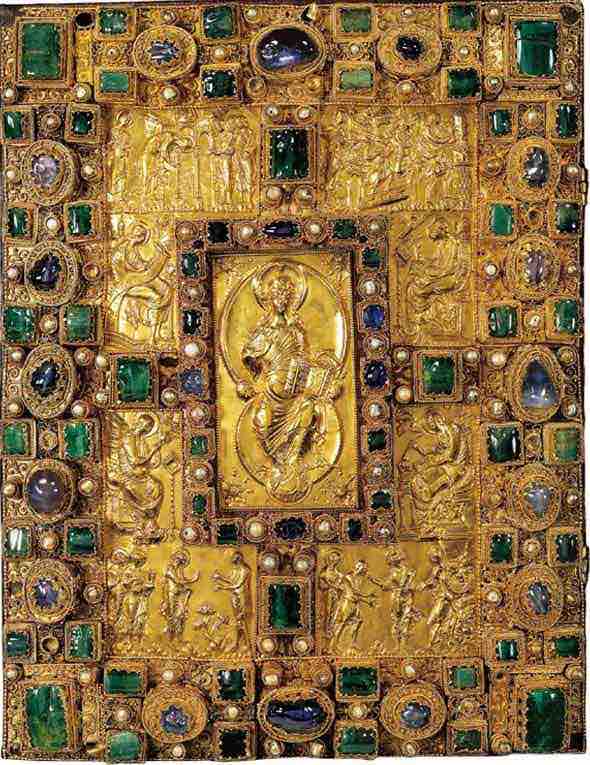

The use of valuable materials is a constant in medieval art. Most illuminated manuscripts of the Early Middle Ages had lavish book-covers decked with precious metal, ivory, and jewels. One of the best examples of precious metalwork in medieval art is the jeweled cover of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram (c. 870). The Codex, whose origin is unknown, is decorated with gems and gold relief. Gold was also used to create sacred objects for churches and palaces, as a solid background for mosaics, or applied as gold leaf to miniatures in manuscripts and panel paintings. Named after Emmeram of Regensburg and lavishly illuminated, the Codex is an important example of Carolingian art, as well of one of very few surviving treasure bindings of the late ninth century.

Cover of the Codex Aureus

Gold and gem-encrusted cover of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, 870. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14000.

Few large stone buildings were constructed between the Constantinian basilicas of the fourth century and the eighth century, although many smaller ones were built during the sixth and seventh centuries. By the early eighth century, the Merovingian dynasty revived the basilica form of architecture. One feature of the basilica is the use of a transept, or the "arms" of a cross-shaped building that are perpendicular to the long nave. Other new features of religious architecture include the crossing tower and a monumental entrance to the church, usually at the west end of the building.

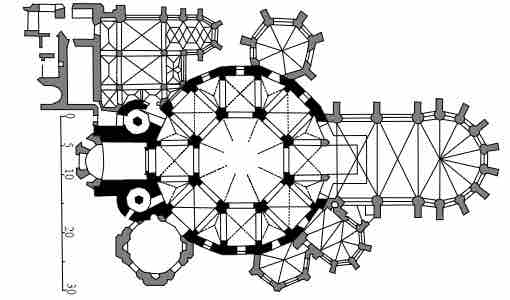

Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel at Aachen (consecrated 805 CE).

The Palatine Chapel is an example of Charlemegne's attempt to revive the values of the Roman Empire under the banner of Christianity. While the plan predates the cruciform basilica, it revives the classical round arch and heavy stone masonry, as well as the east-facing apse of Late Antiquity.