Default risk (or credit risk) of a bond refers to the risk that a bond issuer will default on any type of debt by failing to make payments which it is obligated to do. The risk is primarily that of the bondholder and includes lost principal and interest, disruption to cash flows, and increased collection costs. The loss may be complete or partial and can arise in a number of circumstances. For example, a company is unable to repay amounts secured by a fixed or floating charge over the assets of the company, a business or consumer does not pay a trade invoice when due, a business does not pay an employee's earned wages when due, a business or government bond issuer does not make a payment on a coupon or principal payment when due, an insolvent insurance company does not pay a policy obligation, and an insolvent bank won't return funds to a depositor .

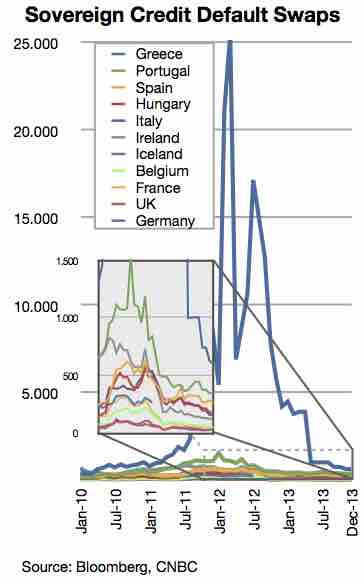

Prices of sovereign credit default swaps

Credit default swaps are an instrument to protect against default risk. This image shows the monthly prices of sovereign credit default swaps from January 2010 till September 2011 of Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Hungary, Italy, Spain, Belgium, France, Germany, and the UK (Greece is illustrated by blue line). Higher credit default swap prices mean that investors perceive a higher risk of default.

To reduce the bondholders' credit risk, the lender may perform a credit check on the prospective borrower, may require the issuer to take out appropriate insurance, such as mortgage insurance or seek security or guarantees of third parties, besides other possible strategies. In general, the higher the risk, the higher will be the interest rate that the issuer will have to pay.

A company's bondholders may lose much or all their money if the company goes bankrupt. Under the laws of many countries (including the United States and Canada), bondholders are in line to receive the proceeds of the sale of the assets of a liquidated company ahead of some other creditors. Bank lenders, deposit holders (in the case of a deposit taking institution such as a bank), and trade creditors may take precedence.

There is no guarantee of how much money will remain to repay bondholders. As an example, after an accounting scandal and a Chapter 11 bankruptcy at the giant telecommunications company Worldcom, in 2004 its bondholders ended up being paid 35.7 cents on the dollar. In a bankruptcy involving reorganization or recapitalization, as opposed to liquidation, bondholders may end up having the value of their bonds reduced, often through an exchange for a smaller number of newly issued bonds.