The best ideas should implemented as quickly as possible—not just by the idea generator but also by others who have a different viewpoint. It is imperative that the idea is honed and refined while it is still fresh. For example, an idea for a new product might start out as a crude model built from polystyrene, foam, or cardboard that will evolve quickly into a more professional prototype.

Product Innovation Approach

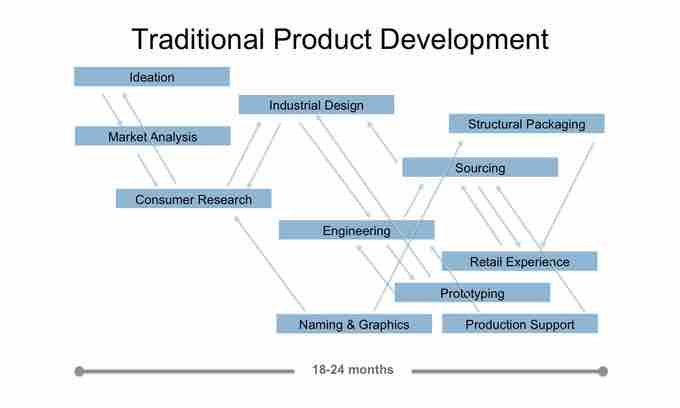

Innovation involves continuous improvement throughout phases of a development program. Phases can be iterative and recursive (meaning that they do not proceed linearly from one to the next; rather, earlier phases can be returned to for further improvement as needed). Such phases include market analysis and consumer research, which progress to design and prototyping, after which follow naming and packaging design and ultimately retail and production support.

Robert Reich observes that profits in the old economy came from economies of scale, i.e., long runs of almost identical products. Thus we had factories, assembly lines, and industries. Today, profits come from speed of innovation and the ability to attract and keep customers. Therefore, while the big winners in the old economy were big corporations, today's big winners are often small, highly flexible groups that devise great ideas, develop trustworthy branding for themselves and their products, and market these effectively. The winning competitors are those who are first at providing lower prices and higher value through intermediaries of trustworthy brands. To keep the lead, however, these companies have to keep innovating lest they fall behind the competition.

The Benefit of Moving First

Speed of innovation poses a major challenge for organizations responding to external change. A high rate of change can be seen in the shortening of product life cycles, increased technological change, increased speed of innovation, and increased speed of diffusion of innovations. These are key challenges for organizations, as the profit generation of new ideas must fit into a slimmer chronological window—thus underlining the great value of being a first-mover.

A first-mover in a given innovation captures the obvious advantage of tapping into a new market before its competitors. This also sometimes allows the first-mover to identify its brand with the new technology (i.e., saying "Google it" as shorthand for online search or calling any and all mp3 players an iPod). These branding hurdles must be tackled by any competitor following in the footsteps of the first-mover.

However, speed is not everything. First-movers encounter serious disadvantages, the most notable of which are freeloaders. First-movers also encounter high fiscal risks in integrating a new product or services into their distribution, and failure often means sunk costs. Latecomers to the game can simply observe the success or failure of other competitors and make more informed (and less risky) decisions about entering the market segment. Similarly, first movers must carefully consider cannibalization—where their new innovative products steal sales from their older products still on store shelves. Speedy innovation and moving first requires great foresight, planning, and managerial skill to execute effectively to minimize risks.