Categorization is the process through which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, classified, and understood. The word "categorization" implies that objects are sorted into categories, usually for some specific purpose. This process is vital to cognition. Our minds are not capable of treating every object as unique; otherwise, we would experience too great a cognitive load to be able to process the world around us. Therefore, our minds develop "concepts," or mental representations of categories of objects. Categorization is fundamental in language, prediction, inference, decision making, and all kinds of environmental interaction.

There are many theories of how the mind categorizes objects and ideas. However, over the history of cognitive science and psychology, three general approaches to categorization have been named.

Classical Categorization

This type of categorization dates back to the classical period in Greece. Plato introduced the approach of grouping objects based on their similar properties in his Socratic dialogues; Aristotle further explored this approach in one of his treatises by analyzing the differences between classes and objects. Aristotle also applied intensively the classical categorization scheme in his approach to the classification of living beings (which uses the technique of applying successive narrowing questions: Is it an animal or vegetable? How many feet does it have? Does it have fur or feathers? Can it fly?), establishing the basis for natural taxonomy.

According to the classical view, categories should be clearly defined, mutually exclusive, and collectively exhaustive. This way, any entity of the given classification universe belongs unequivocally to one, and only one, of the proposed categories. Most modern forms of categorization do not have such a cut-and-dried system.

Conceptual Clustering

Conceptual clustering is a modern variation of the classical approach, and derives from attempts to explain how knowledge is represented. In this approach, concepts are generated by first formulating their conceptual descriptions and then classifying the entities according to the descriptions. So for example, under conceptual clustering, your mind has the idea that the cluster DOG has the description "animal, furry, four-legged, energetic." Then, when you encounter an object that fits this description, you classify that object as being a dog.

Conceptual clustering brings up the idea of necessary and sufficient conditions. For instance, for something to be classified as DOG, it is necessary for it to meet the conditions "animal, furry, four-legged, energetic." But those conditions are not sufficient; other objects can meet those conditions and still not be a dog. Different clusters have different requirements, and objects have different levels of fitness for different clusters. This comes up in fuzzy sets.

Fuzzy Sets

Conceptual clustering is closely related to fuzzy-set theory, in which objects may belong to one or more concepts, in varying degrees of fitness. Our example of the class DOG is a fuzzy set. Perhaps "fox" belongs to this cluster (animal, furry, four-legged, energetic), but not with the same degree of fitness that "wolf" does. Different objects can fit a cluster better than others; fuzzy-set theory is not binary, so it is not always clear whether an object belongs to a cluster or not.

Prototype Theory

Categorization can also be viewed as the process of grouping things based on prototypes. The concept of "necessary and sufficient conditions" usually doesn't work in the messy boundaries of the natural world. Prototype theory is a different way of classifying objects. Essentially, a person has a "prototype" for what an object is; so a person's prototype for DOG may be a mental image of a dog they knew as a child. Their prototype would be their mental idea of a "typical dog." They would classify objects as being dogs or not based on how closely they matched their prototype. Different people have different prototypes for the same kind of object, depending on their experiences.

Prototype theory is not binary; instead it uses graded membership. Under prototype theory, an object can be kind of a dog, and one animal can be more like a dog than another. There are different levels of membership in the category DOG, and those levels are on a hierarchy. Studies have shown that categories at the middle level are perceptually and conceptually the most salient. This means that the category DOG elicits the richest imaging and jumps most easily to mind, relative to GOLDEN RETRIEVER (lower-level hierarchy) and to ANIMAL (higher-level hierarchy).

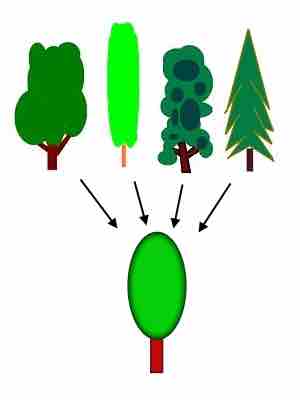

Prototype theory

Under prototype theory, all treelike things will be judged based on an individual's prototype of a tree. The middle category TREE is more salient than the high-level category PLANT or the low-level category ELM.