President Warren G. Harding assumed office in March 1921 while the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline, known as the Depression of 1920–21. By the summer of his first year in office, however, an economic recovery began and Harding convened the Conference of Unemployment in 1921, headed by Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, that advocated economic stimulation through local work projects and encouraged businesses to apply shared work programs. These were among the beneficial policies instituted during Harding’s administration, although others were not so productive or popular.

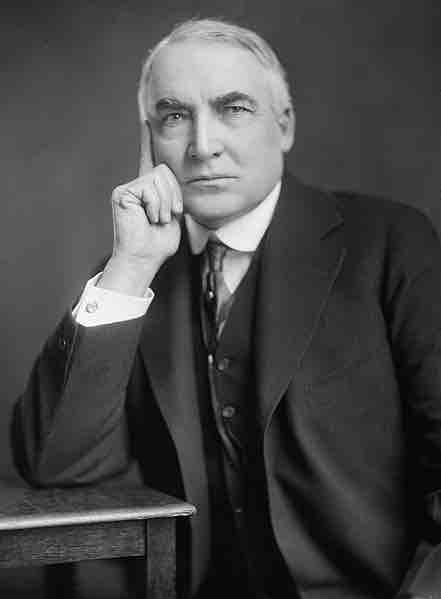

U.S. President Warren G. Harding

President Harding assumed office in 1921, in the midst of a postwar economic decline.

Revenue, Budget and Tariff Acts

Harding believed the federal government should be fiscally managed in a manner similar to the private sector and had campaigned on the slogan, "Less government in business and more business in government." Harding signed the Revenue Act of 1921, which gave large deductions in the amount of taxes the wealthiest Americans had to pay. Revenues to the federal treasury increased substantially in this period. The combined declines in unemployment and inflation (later known as the Misery Index) were among the sharpest in U.S. history. Wages, profits and productivity all made substantial gains during the 1920s.

Considered to be one of his greatest domestic achievements, Harding also signed the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, which established the framework for the modern federal budget. Harding requested and obtained Congressional authorization for the country's first formal budgeting process by establishing the Bureau of the Budget, while the General Accounting Office was created to assure oversight of federal budget expenditures. Harding appointed Charlie Dawes, known for being an effective financier, as the first director of the Bureau of the Budget. Due to these policies, the government budget was cut nearly in half in just two years.

On September 21, 1922, Harding enthusiastically signed the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act, which increased the tariff rates contained in the previous Underwood-Simmons Tariff Act of 1913 to the highest level in the nation's history. The act raised tariffs in America in order to protect factories and farms, although the tariffs established in the 1920s have historically been viewed as a contributing factor in the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

Modernization

The 1920s was a period of modernization for America. On February 27, 1922, Harding implemented the first of a series of Radio Conferences headed by Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. At the first meeting, 30 participants including representatives of amateur radio, government agencies and the radio industry made "cooperative efforts" to ensure the public interest in broadcasting, who would broadcast and for what purpose, and to curb direct advertising.

In what he proclaimed to be the age of the "motor car," Harding signed the Federal Highway Act of 1921, which defined the Federal Aid Road program to develop an immense national highway system. From 1921 to 1923, the government spent a total of $162 million on America's highway system, infusing the U.S. economy with a large amount of capital.

After World War I, 300,000 wounded veterans were in need of hospitalization, medical care, and job training. Harding subsequently pushed for the establishment of the Bureau of Veterans Affairs, later organized as the Department of Veterans Affairs, the first permanent attempt at answering the needs of those who served the nation in times of war.

Civil Rights

In an age of severe racial intolerance, Harding refused to engage in the typical racial animosity. In a speech given on October 26, 1921, in segregated Birmingham, Alabama, Harding made a case for African-American civil rights, making him the first president to openly advocate black political, educational and economic equality during the 20th Century.

Harding placed African-Americans in some important federal positions, such as Walter L. Cohen of New Orleans, Louisiana, whom he named comptroller of customs. Harding also advocated the establishment of an international commission to improve race relations between whites and blacks, but strong political opposition by the Southern Democratic bloc stopped the launch of the commission. Harding had previously spoken out publicly against lynching on October 21, 1921, and he expressed his support for Congressman Leonidas Dyer's federal anti-lynching bill. Known as the Dyer Bill, the measure passed the House of Representatives on January 26, 1922, but was defeated in the Senate by a Democratic filibuster. The bill was at least a step in the right direction, as Congress had not debated a civil rights bill since the 1890 Federal Elections Bill.

Unpopular Policies

In spite of his policies aimed at improving the nation, Harding’s reputation was tarnished through some unpopular decisions and domestic events.

In 1922, a nationwide strike by railway shop men, which became known as the Great Railroad Strike, began under the guidance of labor organizations. Clashes with strikebreakers, shootings by armed company guards, and sabotage by strikers led to the deaths of at least ten people. In another national controversy, Harding clashed with veterans over the issue of providing bonus payments for those who served in World War I, instead favoring a future pension system. Harding vetoed a version of an adjusted compensation act in September 1922, diminishing his overall popularity and costing him support among Republicans who saw his attempts at fiscal responsibility as endangering the party’s prospects in future elections.