HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

The Holy Roman Empire was a multi-ethnic complex of territories in central Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806. The empire gradually evolved into a decentralized, limited elective monarchy composed of hundreds of sub-units, principalities, duchies, counties, Free Imperial Cities, and other domains. The office of Holy Roman Emperor was traditionally elective, although frequently controlled by dynasties. The empire was dominated by the House of Habsburg throughout the Early Modern period.

The Holy Roman Empire was not a highly centralized state like most countries today. Instead, it was divided into dozens—eventually hundreds—of individual entities governed by kings, dukes, counts, bishops, abbots and other rulers, collectively known as princes. There were also some areas ruled directly by the Emperor. At no time could the Emperor simply issue decrees and govern autonomously over the Empire. His power was severely restricted by the various local leaders.

To a greater extent than in other medieval kingdoms such as France and England, the Emperors were unable to gain much control over the lands that they formally owned. Instead, to secure their own position from the threat of being deposed, Emperors were forced to grant more and more autonomy to local rulers, both nobles and bishops.

THE EMPIRE UNDER THE SPANISH HABSBURGS

In 1516, Ferdinand II of Aragon, grandfather of the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, died. Charles initiated his reign in Castile and Aragon, a union which evolved into Spain, in conjunction with his mother. This ensured for the first time that all the realms of what is now Spain would be united by one monarch under one nascent Spanish crown. In 1519, already reigning in Spain as Charles I, he took up the imperial title as Charles V. The relationship between these separate inheritances would be defining elements of his reign and would make the personal union between the Spanish and German crowns short-lived. The latter would end up going to a more junior branch of the Habsburgs in the person of Charles's brother Ferdinand, while the senior branch continued to rule in Spain and in the Burgundian inheritance in the person of Charles's son, Philip II of Spain.

In addition to conflicts between his Spanish and German inheritances, conflicts of religion would be another source of tension during the reign of Charles V. In 1517, Martin Luther launched what would later be known as the Reformation. At this time, many local dukes saw it as a chance to oppose the hegemony of Emperor Charles V. The empire then became fatally divided along religious lines, with the north, the east, and many of the major cities—Strasbourg, Frankfurt and Nuremberg—becoming Protestant while the southern and western regions largely remained Catholic.

Front page of the Peace of Augsburg, 1555.

The treaty between Charles V and the forces of the Schmalkaldic League, an alliance of Lutheran princes, officially ended the religious struggle between the two groups and made the legal division of Christendom permanent within the Holy Roman Empire.

THE EMPIRE AND THE REFORMATION

Charles V continued to battle the French and the Protestant princes in Germany for much of his reign. After his son Philip married Queen Mary of England, it appeared that France would be completely surrounded by Habsburg domains, but this hope proved unfounded when the marriage produced no children. In 1555, Paul IV was elected pope and took the side of France, whereupon Charles finally gave up his hopes of a world Christian empire. He abdicated and divided his territories between Philip and Ferdinand of Austria. The Peace of Augsburg ended the war in Germany and accepted the existence of the Protestant princes, although not Calvinism, Anabaptism, or Swiss Reformed.

Germany would enjoy relative peace for the next six decades. On the eastern front, the Turks continued to loom large as a threat, although war would mean further compromises with the Protestant princes, and so the Emperor sought to avoid it. In the west, the Rhineland increasingly fell under French influence. After the Dutch revolt against Spain erupted, the empire remained neutral, de facto allowing the Netherlands to depart the empire in 1581, a succession acknowledged in 1648. A side effect was the Cologne War, which ravaged much of the upper Rhine.

After Ferdinand died in 1564, his son Maximilian II became Emperor, and like his father, accepted the existence of Protestantism and the need for occasional compromise with it. Maximilian was succeeded in 1576 by Rudolf II, a man who preferred classical Greek philosophy to Christianity and lived an isolated existence in Bohemia. He became afraid to act when the Catholic Church was forcibly reasserting control in Austria and Hungary. Imperial power sharply deteriorated by the time of Rudolf's death in 1612. When Bohemians rebelled against the Emperor, the immediate result was the series of conflicts known as the Thirty Years' War (1618–48), which devastated the empire. Foreign powers, including France and Sweden, intervened in the conflict and strengthened those fighting Imperial power, but also seized considerable territory for themselves. The long conflict so bled the empire that it never recovered its strength.

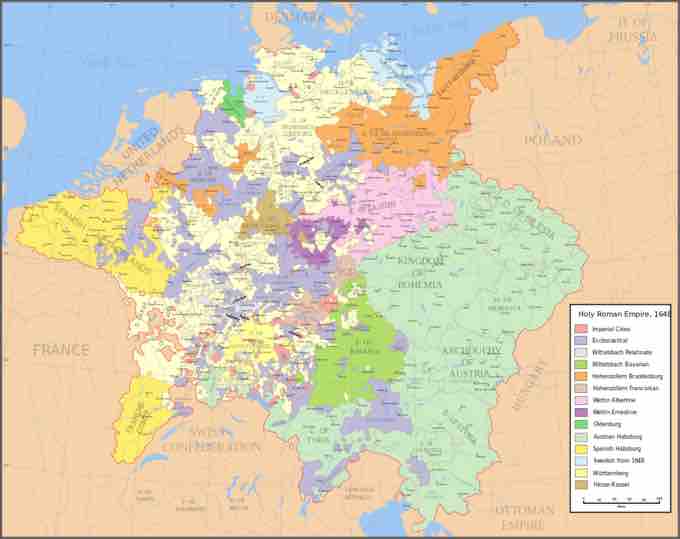

The Holy Roman Empire after the Peace of Westphalia, 1648. Made from the public domain map "Central Europe about 1648" from the Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, at the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas. Source: Wikipedia

The Thirty Years' War so bled the empire that it never recovered its strength.

At the Battle of Vienna (1683), the Army of the Holy Roman Empire, led by the Polish King John III Sobieski, decisively defeated a large Turkish army, ending the western colonial Ottoman advance and leading to the eventual dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire in Europe. The Empire's army was half Polish/Lithuanian Commonwealth forces, mostly cavalry, and half Holy Roman Empire forces (German/Austrian), mostly infantry.

DEMISE

The actual end of the empire came in several steps. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which ended the Thirty Years' War, gave the territories almost complete independence. The Swiss Confederation, which had already established quasi-independence in 1499, as well as the Northern Netherlands, left the empire. The Habsburg Emperors focused on consolidating their own estates in Austria and elsewhere.

The empire was dissolved in 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) abdicated, following a military defeat by the French under Napoleon at Austerlitz. Napoleon reorganized much of the Empire into the Confederation of the Rhine, a French satellite. Francis' House of Habsburg-Lorraine survived the demise of the empire, continuing to reign as Emperors of Austria and Kings of Hungary until the Habsburg empire's final dissolution in 1918 in the aftermath of World War I.