Anisakiasis

[Anisakis simplex] [Contracaeceum sp.] [Pseudoterranova decipiens]

Causal Agents

Anisakiasis is caused by the accidental ingestion of larvae of the nematodes (roundworms) Anisakis simplex and Pseudoterranova decipiens.

Life Cycle:

Adult stages of Anisakis simplex or Pseudoterranova decipiens reside in the stomach of marine mammals, where they are embedded in the mucosa, in clusters. Unembryonated eggs produced by adult females are passed in the feces of marine mammals  . The eggs become embryonated in water, and first-stage larvae are formed in the eggs. The larvae molt, becoming second-stage larvae

. The eggs become embryonated in water, and first-stage larvae are formed in the eggs. The larvae molt, becoming second-stage larvae  , and after the larvae hatch from the eggs, they become free-swimming

, and after the larvae hatch from the eggs, they become free-swimming  . Larvae released from the eggs are ingested by crustaceans

. Larvae released from the eggs are ingested by crustaceans  . The ingested larvae develop into third-stage larvae that are infective to fish and squid. The larvae migrate from the intestine to the tissues in the peritoneal cavity and grow up to 3 cm in length. Upon the host's death, larvae migrate to the muscle tissues, and through predation, the larvae are transferred from fish to fish

. The ingested larvae develop into third-stage larvae that are infective to fish and squid. The larvae migrate from the intestine to the tissues in the peritoneal cavity and grow up to 3 cm in length. Upon the host's death, larvae migrate to the muscle tissues, and through predation, the larvae are transferred from fish to fish  . Fish and squid maintain third-stage larvae that are infective to humans and marine mammals

. Fish and squid maintain third-stage larvae that are infective to humans and marine mammals  .

.

When fish or squid containing third-stage larvae are ingested by marine mammals, the larvae molt twice and develop into adult worms. The adult females produce eggs that are shed by marine mammals  . After ingestion, the anisakid larvae penetrate the gastric and intestinal mucosa, causing the symptoms of anisakiasis.

. After ingestion, the anisakid larvae penetrate the gastric and intestinal mucosa, causing the symptoms of anisakiasis.

Geographic Distribution:

Worldwide, with higher incidence in areas where raw fish is eaten (e.g., Japan, Pacific coast of South America, the Netherlands).

Clinical Presentation

Within hours after ingestion of infected larvae, violent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting may occur. Occasionally the larvae are coughed up. If the larvae pass into the bowel, a severe eosinophilic granulomatous response may also occur 1 to 2 weeks following infection, causing symptoms mimicking Crohn's disease.

Pseudoterranova sp. larval worms.

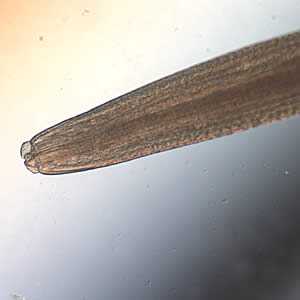

Figure A: Anterior ends of Pseudoterranova sp. worms; images taken at 40x and 200x magnification, respectively.

Figure B: Anterior ends of Pseudoterranova sp. worms; images taken at 40x and 200x magnification, respectively.

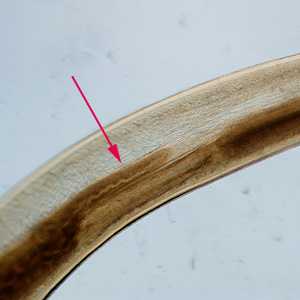

Figure C: Anterior end of Pseudoterranova sp. The red arrow indicates the intestinal cecum.

Figure D: Close-up of the intestinal cecum in the same specimen seen in Figure C

Figure E: Mid-section of a Pseudoterranova sp. worm, showing the esophagus and intestine. Image taken at 40x magnification.

Figure F: Posterior end of Pseudoterranova sp. Image taken at 200x magnification.

Cross sections of anisakid worms.

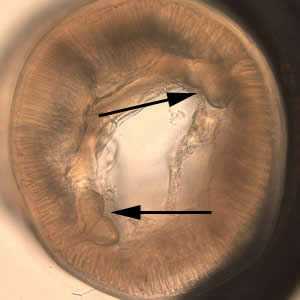

Figure A: Cross-section of Pseudoterranova sp. Note the large butterfly-shaped lateral chords (black arrows), characteristic for this genus.

Figure B: Cross-section of Pseudoterranova sp. viewed under differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy.

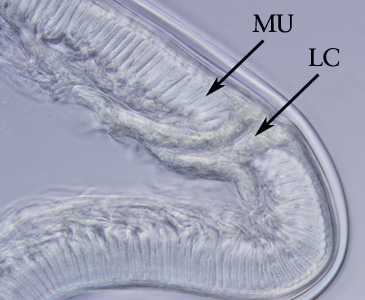

Figure C: Cross-section of Anisakis sp., viewed under DIC microscopy.

Figure D: Higher magnification of the specimen in Figure C. Note the tall, prominent muscle cells (MU) and Y-shaped lateral chords (LC), characteristic for this genus.

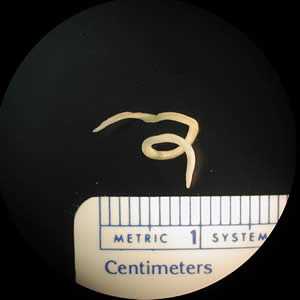

Anisakid worms.

Figure A: L3 larva of Pseudoterranova sp. Ten units = one centimeter.

Figure B: L3 larva of an anisakid worm.

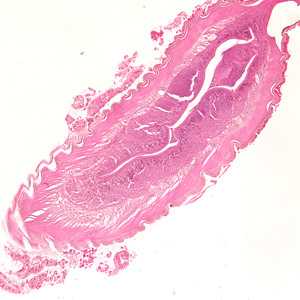

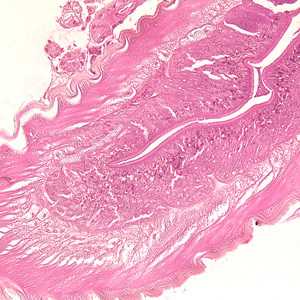

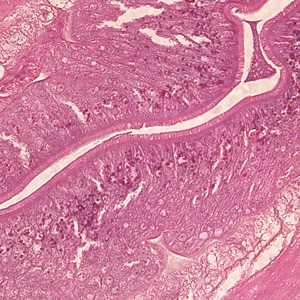

Anisakid worms in tissue specimens, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure A: Larva of an anisakid worm from a gastric biopsy specimen, stained with H&E. Image taken at 100x magnification.

Figure B: Higher magnification (200x) of the specimen in Figure A, showing a close-up of the thick, multi-layered cuticle and tall, prominent muscle cells.

Figure C: Higher magnification (400x) of the specimen in Figures A and B, showing a close-up of the folded intestine with a brush border.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Anterior end of Pseudoterranova sp. The red arrow indicates the intestinal cecum.

Diagnosis can be made by gastroscopic examination during which the larvae are visualized and removed, or by histopathologic examination of tissue removed at biopsy or during surgery. Worms are often coughed up and brought in by patients.

Genus-level identification is not required for patient management but may be accomplished by examination of digestive structures and lateral chords. Examination of digestive structured usually requires clearing in lactophenol. The procedure is as follows:

Preparation of lactophenol

- 1 part phenol, liquefied

- 1 part lactic acid

Liquefy the phenol crystals by heating them in a beaker in a hot water bath or heating block. This should be done in a fume hood. Mix equal parts of the liquefied phenol and lactic acid. An equal volume of glycerin may be added. The glycerin-based solution may be good for nematodes, but prolonged contact may clear the specimen too much.

Procedure

- For specimens submitted in formalin, they may be placed directly into the lactophenol solution. Fresh specimens should be fixed in hot 70% ethanol or 5% formalin for several hours, or kept in one of these solutions overnight.

- Place the specimen in a covered Petri dish, submerged in lactophenol.

- Check the specimen periodically for clearing, starting at about 30 minutes.

- Cleared specimens may be placed back into alcohol or formalin for long-term storage and will revert back to the pre-cleared state.

Procedural Notes

- The amount of time needed to clear will vary depending on the size of the specimen, specimen quality, preservative used, etc.

Treatment Information

It is often possible to diagnose and treat gastric anisakiasis by removal of the worm using an endoscope. Diagnosis of enteric anisakiasis is more difficult; however, it can generally be managed without removal of the worm because the worm will eventually die. Surgery may be required for intestinal or extraintestinal infections when intestinal obstruction, appendicitis, or peritonitis occurs. Successful treatment of anisakiasis with albendazole* 400 mg orally twice daily for 6 to 21 days has been reported in cases with presumptive (highly suggestive history and/or serology) diagnoses.

*Not FDA-approved for this indication

Albendazole

Oral albendazole is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: October 17, 2016

- Page last updated: October 17, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir