Enterobiasis

[Enterobius vermicularis]

Causal Agents

The nematode (roundworm) Enterobius vermicularis (previously Oxyuris vermicularis) also called human pinworm. (Adult females: 8 to 13 mm, adult male: 2 to 5 mm.) Humans are considered to be the only hosts of E. vermicularis. A second species, Enterobius gregorii, has been described and reported from Europe, Africa, and Asia. For all practical purposes, the morphology, life cycle, clinical presentation, and treatment of E. gregorii is identical to E. vermicularis.

Life Cycle

Eggs are deposited on perianal folds . Self-infection occurs by transferring infective eggs to the mouth with hands that have scratched the perianal area

. Self-infection occurs by transferring infective eggs to the mouth with hands that have scratched the perianal area . Person-to-person transmission can also occur through handling of contaminated clothes or bed linens. Enterobiasis may also be acquired through surfaces in the environment that are contaminated with pinworm eggs (e.g., curtains, carpeting). Some small number of eggs may become airborne and inhaled. These would be swallowed and follow the same development as ingested eggs. Following ingestion of infective eggs, the larvae hatch in the small intestine

. Person-to-person transmission can also occur through handling of contaminated clothes or bed linens. Enterobiasis may also be acquired through surfaces in the environment that are contaminated with pinworm eggs (e.g., curtains, carpeting). Some small number of eggs may become airborne and inhaled. These would be swallowed and follow the same development as ingested eggs. Following ingestion of infective eggs, the larvae hatch in the small intestine and the adults establish themselves in the colon

and the adults establish themselves in the colon . The time interval from ingestion of infective eggs to oviposition by the adult females is about one month. The life span of the adults is about two months. Gravid females migrate nocturnally outside the anus and oviposit while crawling on the skin of the perianal area

. The time interval from ingestion of infective eggs to oviposition by the adult females is about one month. The life span of the adults is about two months. Gravid females migrate nocturnally outside the anus and oviposit while crawling on the skin of the perianal area . The larvae contained inside the eggs develop (the eggs become infective) in 4 to 6 hours under optimal conditions

. The larvae contained inside the eggs develop (the eggs become infective) in 4 to 6 hours under optimal conditions . Retroinfection, or the migration of newly hatched larvae from the anal skin back into the rectum, may occur but the frequency with which this happens is unknown.

. Retroinfection, or the migration of newly hatched larvae from the anal skin back into the rectum, may occur but the frequency with which this happens is unknown.

Geographic Distribution

Worldwide, with infections more frequent in school- or preschool-children and in crowded conditions. Enterobiasis appears to be more common in temperate than tropical countries. The most common helminthic infection in the United States (an estimated 40 million persons infected).

Clinical Presentation

Enterobiasis is frequently asymptomatic. The most typical symptom is perianal pruritus, especially at night, which may lead to excoriations and bacterial superinfection. Occasionally, invasion of the female genital tract with vulvovaginitis and pelvic or peritoneal granulomas can occur. Other symptoms include anorexia, irritability, and abdominal pain.

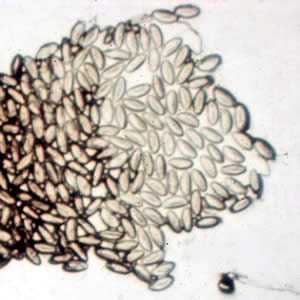

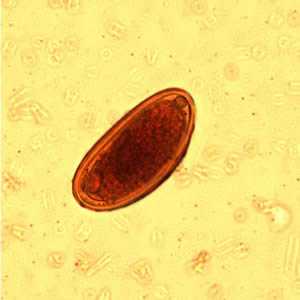

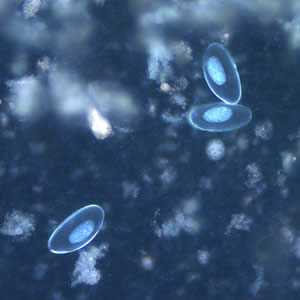

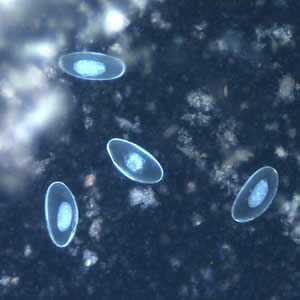

Enterobius vermicularis eggs.

Figure A: Eggs of E. vermicularis in a cellulose-tape preparation.

Figure B: Eggs of E. vermicularis in a wet mount.

Figure C: Egg of E. vermicularis in an iodine-stained wet mount from a formalin concentrate. Image contributed by the Kansas State Public Health Laboratory.

Figure D: Egg of E. vermicularis teased from an adult worm recovered from a colonoscopy. Image contributed by the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, Bureau of Laboratories.

Figure E: Eggs of E. vermicularis viewed under UV microscopy.

Figure F: Eggs of E. vermicularis viewed under UV microscopy.

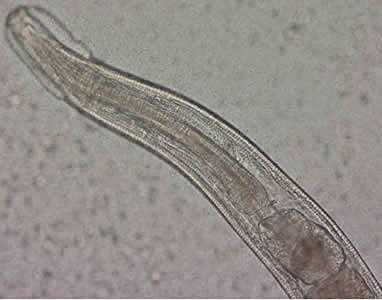

Enterobius vermicularis adult worms.

Figure A: Adult male of E. vermicularis from a formalin-ethyl acetate (FEA) concentrated stool smear. The worm measured 1.4 mm in length. Image contributed by the Centre for Tropical Medicine and Imported Infectious Diseases, Bergen, Norway.

Figure B: Close-up of the anterior end of the worm in Figure A. The esophagus, divided into muscular and bulbous portions and separated by a short, narrow isthmus, is visible in the image, as are the cephalic expansions.

Figure C: Close-up of the posterior end of the worm in Figure A. Note the blunt end. The spicule is withdrawn into the worm in this specimen.

Figure D: Anterior end of an adult female of E. vermicularis, recovered from a colonscopy. Image contributed by the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, Bureau of Laboratories.

Figure E: Posterior end of the worm in Figure D. Note the long, slender pointed tail.

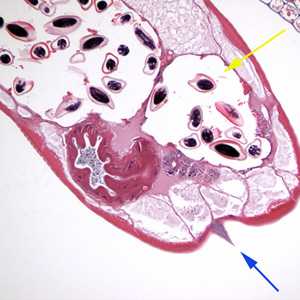

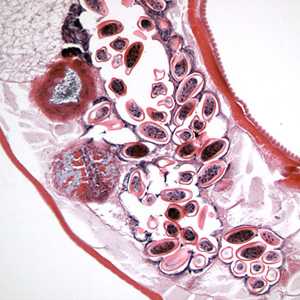

Enterobius vermicularis in tissue, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

Figure A: Cross-section of a male E. vermicularis from tissue, stained with H&E. Notice the presence of the alae (blue arrow), intestine (red arrow) and testis (black arrow).

Figure B: Cross-section of an adult female E. vermicularis from the same specimen shown in Figure A. Note the presence of the alae (blue arrow), intestine (green arrow) and ovaries (black arrows).

Figure C: Cross section of an adult female E. vermicularis stained with H&E, recovered during a colonoscopy. Note the prominent alae (blue arrow) and the presence of eggs (yellow arrow). Image contributed by Sheboygan Memorial Hospital, Wisconsin.

Figure D: Longitudinal section of an adult female E. vermicularis from the same specimen as Figure C. Note the presence of many eggs.

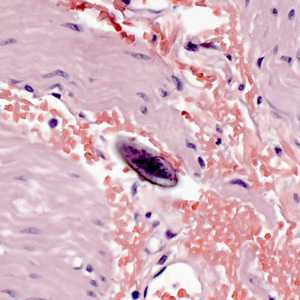

Figure E: Egg of E. vermicularis in a colon biopsy specimen, stained with H&E.

Figure F: Egg of E. vermicularis in a colon biopsy specimen, stained with H&E.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Microscopic identification of eggs collected in the perianal area is the method of choice for diagnosing enterobiasis. This must be done in the morning, before defecation and washing, by pressing transparent adhesive tape ("Scotch test", cellulose-tape slide test) on the perianal skin and then examining the tape placed on a slide. Alternatively, anal swabs or "Swube tubes" (a paddle coated with adhesive material) can also be used. Eggs can also be found, but less frequently, in the stool, and occasionally are encountered in the urine or vaginal smears. Adult worms are also diagnostic, when found in the perianal area, or during ano-rectal or vaginal examinations.

Diagnostic Findings

More on: Morphologic comparison with other intestinal parasites.

Treatment Information

The medications used for the treatment of pinworm are mebendazole, pyrantel pamoate, or albendazole. Any of these drugs are given in one dose initially, and then another single dose two weeks later. Pyrantel pamoate is available without prescription. The second dose of medication is to eliminate possible re-infection since the first dose of medication. Health practitioners and parents should weigh the health risks and benefits of these drugs for patients under 2 years of age.

The safety of drugs used to treat pinworm have not been studied for pregnant women. If the infection is compromising the pregnancy (i.e. weight loss, sleeplessness) then treatment can be considered, but should be withheld until the 3rd trimester when the risk, if any, to the fetus is likely to be reduced. Breastfeeding should not be withheld during mebendazole therapy. Only about 2%-10% of an oral dose is absorbed and as expected, the amounts of the drug excreted in milk are below the level of detection and appear to be clinically insignificant. Excretion in breast milk of the other drugs used to treat pinworm is not as well characterized.

Mebendazole

Mebendazole is available in the United States only through compounding pharmacies.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

Pyrantel Pamoate

Pyrantel pamoate is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

Albendazole

Oral albendazole is available for human use in the United States.

Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir