Myiasis

[Cochliomyia hominovorax] [Dermatobia hominis] [Cuterebra spp.] [Oestrus ovis] [Cordylobia anthropophaga]

[Lucilia spp.] [Phormia regina]

Causal Agent

Myiasis is infection with the larval stage (maggots) of various flies. Flies in several genera may cause myiasis in humans. Dermatobia hominis is the primary human bot fly. Cochliomyia hominovorax is the primary screwworm fly in the New World and Chrysomya bezziana is the Old World screwworm. Cordylobia anthropophaga is known as the tumbu fly. Flies in the genera Cuterebra, Oestrus and Wohlfahrtia are animal parasites that also occasionally infect humans.

Adults of Dermatobia hominis are free-living flies  . Adults capture blood-sucking arthropods (such as mosquitoes) and lay eggs on their bodies, using a glue-like substance for adherence

. Adults capture blood-sucking arthropods (such as mosquitoes) and lay eggs on their bodies, using a glue-like substance for adherence  . Bot fly larvae develop within the eggs, but remain on the vector until it takes a blood meal from a mammalian or avian host. Newly-emerged bot fly larvae then penetrate the host's tissue

. Bot fly larvae develop within the eggs, but remain on the vector until it takes a blood meal from a mammalian or avian host. Newly-emerged bot fly larvae then penetrate the host's tissue  . The larvae feed in a subdermal cavity

. The larvae feed in a subdermal cavity  for 5-10 weeks, breathing through a hole in the host's skin. Mature larvae drop to the ground

for 5-10 weeks, breathing through a hole in the host's skin. Mature larvae drop to the ground  and pupate in the environment. Larvae tend to leave their host during the night and early morning, probably to avoid desiccation. After approximately one month, the adults emerge

and pupate in the environment. Larvae tend to leave their host during the night and early morning, probably to avoid desiccation. After approximately one month, the adults emerge  to mate and repeat the cycle. Other genera of myiasis-causing flies (including Cochliomyia, Cuterebra, and Wohlfahrtia) have a more direct life cycle, where the adult flies lay their eggs directly in, or in the vicinity of, wounds on the host

to mate and repeat the cycle. Other genera of myiasis-causing flies (including Cochliomyia, Cuterebra, and Wohlfahrtia) have a more direct life cycle, where the adult flies lay their eggs directly in, or in the vicinity of, wounds on the host  . In Cochliomyia and Wohlfahrtia infestations, larvae feed in the host for about a week, and may migrate from the subdermis to other tissues in the body, often causing extreme damage in the process.

. In Cochliomyia and Wohlfahrtia infestations, larvae feed in the host for about a week, and may migrate from the subdermis to other tissues in the body, often causing extreme damage in the process.

Geographic Distribution

Dermatobia hominis and C. hominovorax are Neotropical species, ranging from Mexico into South America. The Congo floor maggot (Auchmeromyia luteola) and Cordylobia anthropophaga are distributed in Africa south of the Sahara. Wohlfahrtia magnifica occurs in the Mediterranean basin, Near East, and Central and Eastern Europe; W. vigil occurs in northern United States and Canada. Cuterebra species are found in the New World. Oestrus ovis is found throughout the world in areas where sheep are tended.

Clinical Presentation

Infestations with D. hominis are often characterized by cutaneous swellings on the body or scalp that may produce discharges and be painful. Death is rare, but there have been instances of cerebral myiasis in children where larvae enter the brain. Infestations with C. hominovorax, which causes wound myiasis, can be more serious, as this species may travel through living tissue in the body and not stay subdermal like most of the other species of flies that cause myiasis. Death has occurred with severe infestations of C. hominovorax. Secondary bacterial infections may also occur. Oestrus ovis has been known to cause a condition called ophthalmomyiasis, which is infection of the eye with fly larvae. Flies in the genera Phormia and Phaenicia cause facultative myiasis, where adult flies lay their eggs in pre-existing, festering wounds and do not invade healthy, living tissue.

Cochliomyia hominovorax.

Figure A: Larva of C. hominovorax removed from the forehead of a patient who traveled to the Amazon region of South America.

Figure B: Close-up of the anterior end of a larva, showing the mandibles.

Figure C: Close-up of the anterior end of a larva, showing the mandibles and one of the anterior spiracles.

Figure D: Higher magnification of an anterior spiracle.

Figure E: Close-up of the posterior end of a larva, showing the posterior spiracles. Note the spiracles have three slits and a weak ecdysial scar.

Figure F: The cephalopharyngeal skeleton of C. hominovorax dissected from the head of a larva, showing the mandible structure.

Dermatobia hominis.

Figure A: Four larvae of D. hominis, removed from a human host.

Figure B: Close-up of the anterior end of one of the larvae from Figure A, showing the mandibles.

Figure C: Close-up of the posterior end of one of the larvae from Figure A.

Figure D: Anterior end of a larva of D. hominis. Image from a specimen courtesy of the Idaho State Health Department.

Cuterebra spp.

Figure A: Anterior end of a larva of a bot fly in the genus, Cuterebra.

Figure B: Posterior end of the larva in Figure A.

Oestrus ovis.

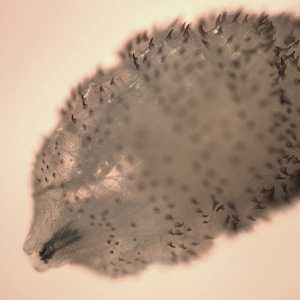

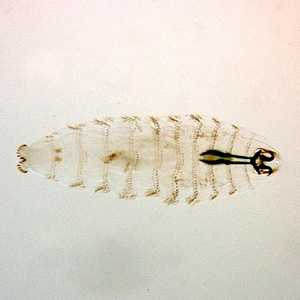

Figure A: First instar larva of Oestrus ovis, taken from the conjunctiva of patient in New Zealand. Image courtesy of Auckland City Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand.

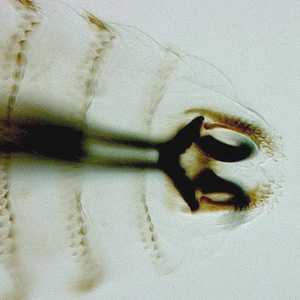

Figure B: Close-up of the anterior end of the larva in Figure A, showing the cephalopharyngeal skeleton and mandibles.

O_ovis_posterior_NZ.jpg

Figure D: First instar larva of O. ovis, collected from the eye of a patient in India presenting with conjunctivitis. Image courtesy of the L V Prasad Eye Institute, Banjara Hills, India.

Cordylobia anthropophaga.

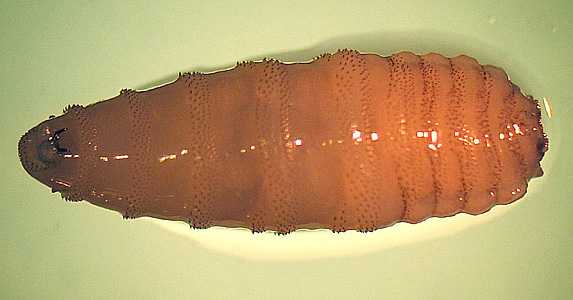

Figure A: Third instar larva of C. anthropophaga, collected from a lesion on the wrist of a patient who traveled to Nigeria. Image courtesy of the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA.

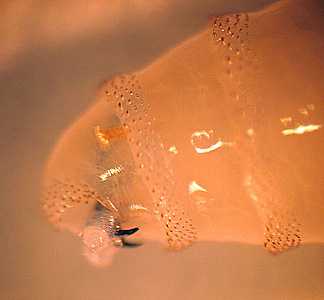

Figure B: Close-up of the anterior end of the specimen in Figure A.

Figure C: Higher-magnification of the specimen in Figure B, showing a close-up of the mandibles.

Figure D: Posterior spiracles of the specimen in Figures A-C.

Phormia regina.

Figure A: Third instar larva of P. regina, collected in the wound of a patient.

Figure B: Close-up of the posterior spiracles of the specimen in Figure A.

Lucilia spp.

Figure A: Mouthparts of Lucilia sp., removed from a surgical wound of a patient. Image courtesy of the Washington State Public Health Laboratories.

Figure B: Posterior end of the specimen in Figure A.

Figure C: Posterior spiracles of the specimen in Figure A. Notice the three, straight slits and a complete peritreme that is not very thick.

Figure D: Posterior spiracles of the specimen in Figure A. Notice the three, straight slits and a complete peritreme that is not very thick.

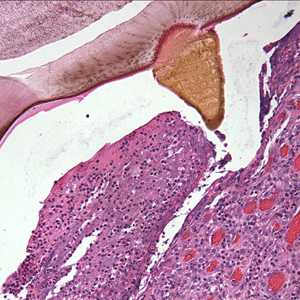

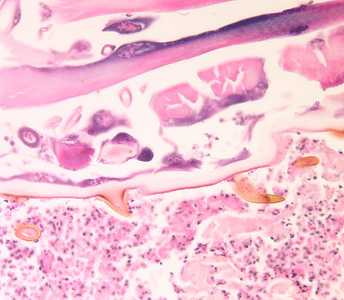

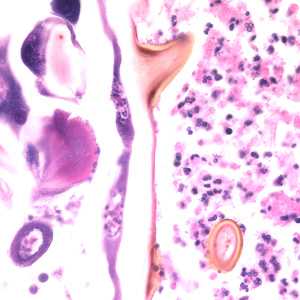

Myiasis in tissue specimens.

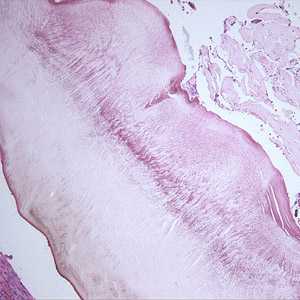

Figure A: Cross-sections of a bot fly larva (unidentified) taken from the right ear of a patient who traveled to Belize. This image shows a cross-section of the body wall.

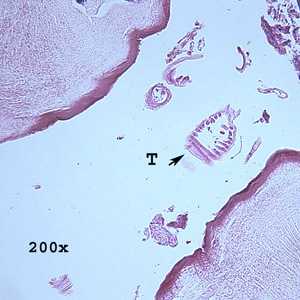

Figure B: Cross-sections of a bot fly larva (unidentified) taken from the right ear of a patient who traveled to Belize. This image shows remnants of the trachea (T).

Figure C: Cross-sections of a bot fly larva (unidentified) taken from the right ear of a patient who traveled to Belize. This image shows three cuticular spines.

Figure D: Cross-sections of a bot fly larva (unidentified) taken from the right ear of a patient who traveled to Belize. This image shows a close-up of one of the spines.

Figure E: Cross-section of the larva of the tumbu fly (Cordylobia anthropophaga) in a skin biopsy from a patient who traveled to western Africa.

Figure F: Higher-magnification of the image in Figure E, showing a close-up of the cuticular spines.

Adults of flies that cause myiasis in humans.

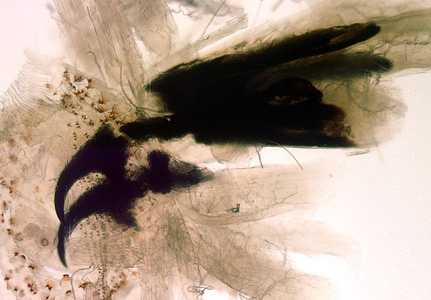

Figure A: Adult of Dermatobia hominis, the human bot fly. Image taken from a specimen courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Natural History, University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

Figure B: Adult of Cochliomyia hominovorax, the primary screwworm fly in the New World. Image taken from a specimen courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Natural History, University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

Figure C: Adult of Cuterebra sp. Cuterebra spp. are primarily parasites of rodents and lagomorphs, although human infections are rare. Images taken from specimens courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Natural History, University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

Figure D: Adult of Cuterebra sp. Cuterebra spp. are primarily parasites of rodents and lagomorphs, although human infections are rare. Images taken from specimens courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Natural History, University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

Diagnostic Findings

The diagnosis of myiasis is made by the finding of fly larvae in tissue. Identification to the genus or species level involves comparing certain morphological structures on the larvae, including the anterior and posterior spiracles, mouthparts and cephalopharyngeal skeleton, and cuticular spines. Travel history can also be helpful for genus or species-level identification.

Treatment Information

Fly larvae need to be surgically removed. No medications approved by the FDA are available for treatment.

Preventing possible exposure is key advice for patients traveling in tropical areas of Africa and South America. Those with untreated and open wounds are more at risk.

References

- Guerrant RL, Walker DH, and Weller PE. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens, and Practice, pp. 1371-3, 2006.

DPDx is an education resource designed for health professionals and laboratory scientists. For an overview including prevention and control visit www.cdc.gov/parasites/.

- Page last reviewed: May 3, 2016

- Page last updated: May 3, 2016

- Content source:

- Global Health – Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria

- Notice: Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS, CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- Maintained By:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir