Solve Foodborne Outbreaks

Did you know you can help disease detectives find and solve foodborne disease outbreaks? Learn some ways you can help protect others from getting sick.

Foodborne Illness Basics

Foodborne illness, or food poisoning, is an enteric (gastrointestinal) infection caused by food that contains harmful germs, such as Salmonella, Escherichia coli, or Listeria. Most illnesses happen suddenly and last a short time, and most people get better without treatment. Foodborne illnesses can be more serious, especially for people with certain underlying medical conditions or other reasons.

Foodborne disease outbreaks are caused by most common types of foods [197 KB] including produce, seafood, dairy, chicken, beef, pork and processed foods. Also, some types of animals or pets can carry these germs and can make people sick.

Foodborne Disease Outbreaks

Each year, about 1 in 6 Americans (or 48 million people) get sick from a foodborne illness. Many of these cases occur one by one, but some illnesses are part of outbreaks.

If two or more people have the same illness in a given period and area, it’s called a cluster. The cluster becomes an outbreak if the investigation of these illnesses finds that these people became infected from the same food or other common source.

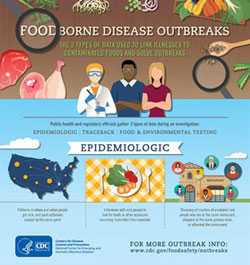

CDC uses three types of information to solve outbreaks caused by food: epidemiologic, traceback, and food and environmental testing information. Each piece of information provides another clue about what may be causing an outbreak.

Finding the source of an outbreak is important, because the food could still be in stores, restaurants or kitchens and therefore could make more people sick. By investigating outbreaks, we can stop them so more people don’t get sick and we can learn about what went wrong, to keep similar outbreaks from happening in the future.

How You Can Help

You play an important role in helping the network of people and organizations who investigate foodborne disease outbreaks.

Three ways you can help when you’re sick with food poisoning:

1. Report Your Illness to Your Health Department

If you have food poisoning, or got sick after contact with an animal, report it to your local or state health department. You can refer to your state health department website to find more information about how to contact your local health department.

Reporting your illness and symptoms helps your local or state health department identify foodborne disease outbreaks. Health departments track reports of illnesses and look for groups of people with similar symptoms and exposures.

2. Talk to Your Health Care Provider

Talk to your health care provider about testing you for foodborne disease.

Health care providers can order stool or blood tests that can tell them if you have a foodborne disease. These tests are sent to laboratories where germs are cultured (grown) from your sample and the results are uploaded to a database called PulseNet. PulseNet is a network of local and state public health laboratories and federal food regulatory laboratories that performs DNA fingerprinting of foodborne germs. These “DNA fingerprints” can be used to compare the infecting bacteria with that from other sources to determine if they’re linked.

If you get sick, write down what you ate and what you did.

3. Write Down What You Ate and What You Did

If you get sick with food poisoning, make a food diary and write everything down that you can remember eating in the week before you started to get sick, including any restaurants or special events you may have attended. Remember, the time between swallowing a germ and feeling the first signs of illness is typically 2-3 days, and sometimes longer. The contaminated food is usually not the last food eaten before a person feels sick.

It is also important to write down any contact with pets or other animals you remember in the days before you got sick. Gather and save any food receipts you have kept from the grocery store, market, or restaurants. You may be asked to share these with investigators.

Usually, disease detectives interview sick people over the phone to find out what they might have eaten in the days before their illness started.

Three ways you can help when you’re not sick with food poisoning:

Keep your food receipts from the store, market, and restaurants.

1. Keep Food Receipts and Enroll in Shopper Card Programs

Keep your food receipts from the store, market, and restaurants. Routinely keeping these receipts can help you remember what you ate if you get sick.

Shopper card programs at stores and markets can track your purchases and provide information on foods, brands and other details that can help disease detectives during outbreak investigations. Investigators will only use your shopper card information with your permission.

2. Keep Food Labels

If you buy food and freeze it, freeze the original packaging or label with the food. This helps identify what the food is and trace where it came from during an outbreak investigation.

Check out this infographic [2.87 MB] about how health officials solve foodborne outbreaks.

3. Participate in Disease Detective Investigations

Sometimes during outbreak investigations, public health officials conduct an epidemiologic study called a “case-control study.”

Officials interview sick people (cases) and healthy people (controls). Then they compare what the two groups ate and the things they did. If a public health official contacts you to answer questions about an outbreak, take the time to participate – you’ll be helping with the investigation. The information you share may provide important clues to help disease detectives solve the outbreak and prevent others from getting sick!

Public Health Partners

Solving outbreaks requires a team effort. CDC foodborne disease detectives work with laboratorians in PulseNet, state and local health department officials, regulatory partners at the Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and other partners to ensure rapid, coordinated detection and response to multistate outbreaks of foodborne illnesses.

More Information

Outbreak Investigations

- Investigating Outbreaks

- Multistate and Nationwide Foodborne Outbreak Investigations: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Key Players in Foodborne Outbreak Response

- Lists of Selected Multistate Foodborne Outbreak Investigations

- Foodborne Outbreak Online Database (FOOD Tool)

- Timeline for Reporting Cases of Salmonella Infection

- Timeline for Reporting Cases of E. coli O157 Infection

Gastrointestinal (Enteric) Diseases from Animals

- Reports of Selected Multistate Outbreak Investigations Linked to Animals and Animal Products

- Zoonotic Diseases (Diseases from Animals )

Food Safety

Federal Agencies

- Page last reviewed: June 14, 2017

- Page last updated: June 14, 2017

- Content source:

- National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases

- Page maintained by: Office of the Associate Director for Communication, Digital Media Branch, Division of Public Affairs

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir