Attribution of Foodborne Illness: Findings

Podcast

Each year, an estimated 48 million people (1 in 6) get sick from food eaten in the United States. Major known pathogens account for more than 9 million of these illnesses. However, linking individual illnesses to a particular food is rarely possible except during an outbreak.

To find out which foods make us ill, CDC developed a comprehensive set of estimates of the food sources of all foodborne illnesses acquired in the United States. The estimates are found in the study, Attribution of Foodborne Illnesses, Hospitalizations, and Deaths to Food Commodities by Using Outbreak Data, United States, 1998–2008.

What is this study about?

This study addresses the important question: Which foods make us sick?

For the first time, CDC developed a comprehensive set of estimates of the food sources of all foodborne illnesses acquired in the United States. The paper provides a historical baseline of estimates that will be further refined over time with more data and improved methods.

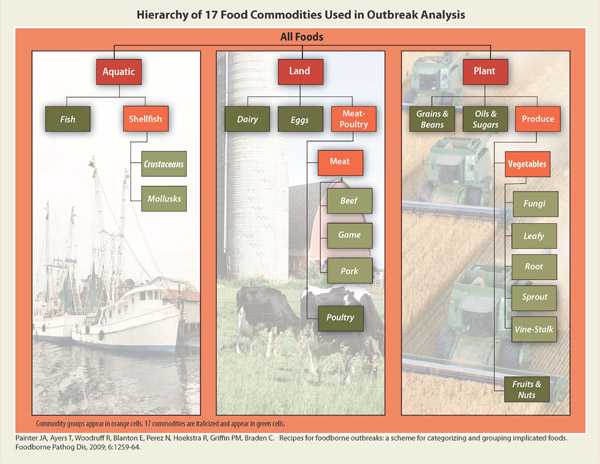

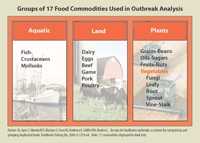

The paper focuses on known causes of illness and uses data from nearly 4,600 outbreaks to estimate the number of illnesses attributed to each of 17 food categories (called “commodities” in the paper). This is the first time CDC has attempted such a comprehensive set of estimates. Figure A.

Why is this study important?

This study offers estimates of the food categories responsible for foodborne ilnesses.

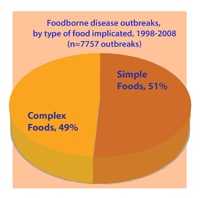

CDC developed a method of attributing illnesses to specific food categories based on a decade of outbreak data, including outbreaks caused by complex foods in which the contaminated ingredient was uncertain (that is, foods that have ingredients from several food categories). Figure A.

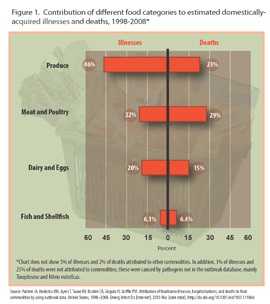

Among all types of foods, produce accounted for nearly half of illnesses, which were most often caused by norovirus. The most common sources of fatal infections were meat and poultry, much due to Salmonella and Listeria, Figure B. These attribution estimates are important because they can help regulatory agencies and industry target prevention efforts that will improve the safety of the foods that we need and that we love to eat.

What did the study show?

Figure B

The study attributed Illnesses to all of the 17 food categories.

- Figure B shows the contributions of different food categories (called commodities in the study) to estimated illnesses and deaths.

- Figure D shows the main groupings of food categories.

- Figure E gives examples of foods in categories.

Produce (a combination of six plant food categories [Fruits-Nuts, Fungi vegetables, Leafy vegetables, Root vegetables, Sprout vegetables, Vine-Stalk vegetables]) accounted for nearly half of illnesses (46%).

- Among the individual food categories, leafy vegetables accounted for the most illnesses. Many of those illnesses (46%) were caused by norovirus.

Meat and poultry, a combination of four animal food categories, Beef, Game, Pork, and Poultry, accounted for fewer illnesses, but for 29% of deaths.

- Poultry accounted for the most deaths (19%); many of those were caused by Listeria and Salmonella infections.

- This rate is partly due to three large Listeria outbreaks linked to sliced processed deli turkey meat; the last such large outbreak occurred in 2002.

Your findings attribute many illnesses from produce to norovirus. Do you know how food became contaminated with norovirus?

This study does not address where contamination of food occurs along the food production chain. A CDC study, “Epidemiology of Foodborne Norovirus Outbreaks, United States, 2001-2008,” looked at this issue in relation to norovirus.

What are the advantages of using outbreak data to estimate the sources of foodborne illnesses?

Outbreak investigations definitively link illnesses to particular foods and pathogens

- Outbreaks are caused by a wide range of agents, including bacteria, viruses, parasites, toxins, and other chemicals so they provide good coverage of foodborne agents.

- Outbreak investigations capture data on common and uncommon pathogens, and on common and uncommon foods.

What are some of the limitations of the study?

- Estimates were not made for pathogens that did not cause outbreaks. Toxoplasma and Vibrio vulnificus did not cause outbreaks but have high fatality rates. Adding these pathogens might result in Meat and Mollusks (e.g., oysters, clams) being more important source of deaths than is indicated in the study.

- The study used data from an 11-year period and did not account for changes over this period. A shorter, more recent period is desirable when major implicated commodities have changed. For example, Listeria outbreaks caused by contamination of ready-to-eat meats markedly decreased after 2002.

- The estimates are presented as ranges of high, low, and most likely estimates for the number of illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths attributed to each food category. The ranges reflect the uncertainty in the estimates.

- The estimates depend on the general assumption that the foods implicated in outbreaks are the same foods that cause individual illnesses not part of outbreaks.

- The risk for foodborne illness is just one part of the risk-benefit equation for foods; the health benefits of consuming a diet high in fruits and vegetables must also be considered.

Does this mean I should not eat produce and poultry?

No, that is not the message from this paper. A healthy and safe diet is an important part of a healthy lifestyle. These findings do not mean that people should avoid certain categories of foods.

- Fruits and Vegetables: The 2010 Dietary Guidelines encourage Americans to eat more fruits and vegetables as a part of a healthy diet. Eating fruits and vegetables is associated with reduced risk of many chronic diseases, including heart attack, stroke, and certain types of cancer. When properly cleaned, separated, cooked, and stored to limit contamination, fruits and vegetables safely provide some essential nutrients that would otherwise be lacking in most American diets.

- Raw Poultry: Food items, like chicken, often contains harmful bacteria such as Salmonella and Campylobacter. Washing poultry does not remove bacteria.

- Kill these bacteria by cooking chicken to the proper temperature.

- Use a food thermometer to ensure that cooked foods reach a safe internal temperature: 165°F for poultry, 145°F for whole meats (allowing the meat to rest for 3 minutes before carving or consuming), and 160°F for ground meats.

What types of additional data and methods are you planning to use to improve the estimates?

The attribution of illness to foods can be done in several different ways, some highly specific for one type of infection or one type of food, and others more general.

- For example, by comparing the characteristics of Salmonella found in foods and animals with those found in people, one can attribute Salmonella infections back to specific animal sources.

- A working group of scientists from CDC, FDA and USDA has been collaborating on several projects to improve these estimates. The Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration (IFSAC) is bringing together more data from across the agencies, and evaluating methods for analyzing them, and will be providing more refined estimates in the future.

- Page last reviewed: July 16, 2016

- Page last updated: July 16, 2016

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir