Childhood Nutrition Facts

Overview

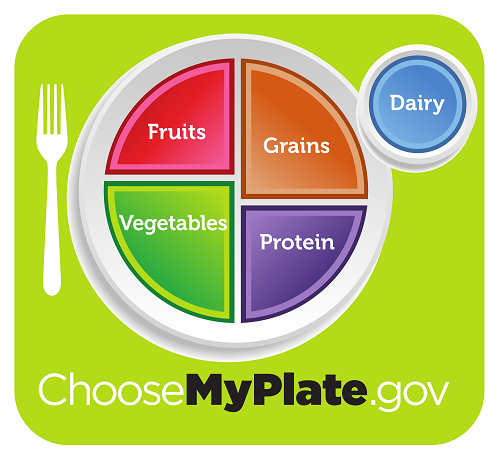

Healthy eating in childhood and adolescence is important for proper growth and development and to prevent various health conditions.1,2 The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend that people aged 2 years or older follow a healthy eating pattern that includes the following2:

- A variety of fruits and vegetables

- Whole grains

- Fat-free and low-fat dairy products

- A variety of protein foods

- Oils

These guidelines also recommend that individuals limit calories from solid fats (major sources of saturated and trans fatty acids) and added sugars, and reduce sodium intake.2 Unfortunately, most children and adolescents do not follow the recommendations set forth in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.2–4

Benefits of Healthy Eating

Healthy eating can help individuals achieve and maintain a healthy body weight, consume important nutrients, and reduce the risk of developing health conditions such as1,2

- High blood pressure

- Heart disease

- Diabetes

- Cancer

- Osteoporosis

- Iron deficiency

- Dental caries (cavities)

Consequences of a Poor Diet

- A poor diet can lead to energy imbalance (e.g., eating more calories than your body uses) and can increase the risk of becoming overweight or obese.1,5

- A poor diet can increase the risk for lung, esophageal, stomach, colorectal, and prostate cancers.2,6

- Hunger and food insecurity (i.e., reduced food intake and disrupted eating patterns due to a lack of household income and other resources for food) might increase the risk for lower dietary quality and undernutrition. In turn, undernutrition can negatively affect overall health, cognitive development, and school performance.7–9

Eating Behaviors of Young People

- Between 2001 and 2010, consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among children and adolescents decreased, but still accounts for 10% of total caloric intake.10

- Between 2003 and 2010, total fruit intake and whole fruit intake among children and adolescents increased. However, most youth still do not meet fruit and vegetable recommendations.11,12

- Empty calories from added sugars and solid fats contribute to 40% of daily calories for children and adolescents age 2–18 years—affecting the overall quality of their diets. Approximately half of these empty calories come from six sources: soda, fruit drinks, dairy desserts, grain desserts, pizza, and whole milk.4 Most youth do not consume the recommended amount of total water.13

Diet and Academic Performance

- Schools are in a unique position to provide students with opportunities to learn about and practice healthy eating behaviors.15

- Eating a healthy breakfast is associated with improved cognitive function (especially memory), reduced absenteeism, and improved mood.16–18

- Adequate hydration may also improve cognitive function in children and adolescents, which is important for learning.19–23

Key Resources

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015–2020

- MyPlate

- School Health Guidelines to Promote Healthy Eating and Physical Activity

- CDC School Nutrition Environment

- National Cancer Institute’s Risk Factor Monitoring and Methods: Food Sources Data on US dietary intake of the top food sources

- More Publications & Resources (http://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/npao/publications.htm)

References

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015.

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.

- Krebs-Smith SM, Guenther PM, Subar AF, et al. Americans Do Not Meet Federal Dietary Recommendations. Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140:1832–1838.

- Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary Sources of Energy, Solid fats, and Added Sugars Among Children and Adolescents in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2010;110:1477–1484.

- Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004.

- Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, et al. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention: Reducing the Risk of Cancer with Healthy Food Choices and Physical Activity. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2006;56:254–281.

- Kaiser LL, Townsend MS. Food Insecurity Among US Children: Implications for Nutrition and Health. Topics in Clinical Nutrition. 2005;20:313–320.

- Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Food Insufficiency and American School-aged Children’s Cognitive, Academic and Psychosocial Developments. Pediatrics 2001;108:44–53.

- Kleinman RE, Murphy JM, Little M, et al. Hunger in Children in the United States: Potential Behavioral and Emotional Correlates. Pediatrics 1998;101:1–6.

- Mesirow MA, Welsh JA. Changing Beverage Consumption Patterns Have Resulted in Fewer Liquid Calories in the Diets of US Children: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2010. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2015;115(4):559–66.

- Kim SA, Moore LV, Galuska D, et al. Vital Signs: Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Children—United States, 2003–2010. MMWR. 2014 Aug 8;63(31):671–6.

- Drewnowski A, Rehm CD. Socioeconomic Gradient in Consumption of Whole Fruit and 100% fruit juice among US children and adults. Nutr J. 2015;14:3.

- Drewnowski A, Rehm CD, Constant F. Water and beverage consumption among children age 4–13y in the United States: analyses of 2005–2010 NHANES data. Nutr J. 2013;12(1):85.

- US Department of Agriculture. ChooseMyPlate.gov.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School health guidelines to promote healthy eating and physical activity. MMWR. 2011;60(RR05):1–76.

- Taras HL. Nutrition and Student Performance at School. Journal of School Health. 2005;75:199–213.

- Rampersaud GC, Pereira MA, Girard BL, et al. Breakfast Habits, Nutritional Status, Body Weight, and Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105:743–760.

- Hoyland A, Dye L, Lawton CL. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Breakfast on the Cognitive Performance of Children and Adolescents. Nutrition Research Reviews. 2009;22:220–243.

- Popkin BM, D’Anci KE, Rosenberg IH. Water, Hydration, and Health. Nutrition Reviews. 2010;68(8):439–458.

- Kempton MJ, Ettinger U, Foster R, et al. Dehydration Affects Brain Structure and Function in Healthy Adolescents. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32:71–79.

- Edmonds CJ, Jeffes B. Does Having a Drink Help You Think? 6 to 7-year-old children show improvements in cognitive performance from baseline to test after having a drink of water. Appetite. 2009;53:469–472.

- Edmonds CJ, Burford D. Should Children Drink More Water? The effects of drinking water on cognition in children. Appetite. 2009;52:776–779.

- Benton D, Burgess N. The Effect of the Consumption of Water on the Memory and Attention of Children. Appetite. 2009;53:143–146.

- Page last reviewed: May 16, 2017

- Page last updated: May 16, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir