Health Care Providers

Diagnosis, Treatment and Testing

- New! – Feeling Worse After Treatment? Maybe It’s Not Lyme Disease

- Treatment

- 2006 IDSA Treatment Guidelines

- Two-tier testing explained

- Tests that are NOT recommended (including CD57, urine antigen testing, etc.)

- Tickborne Diseases of the United States: A Reference Manual for Health Care Providers, Fourth Edition (2017).

- Print or save the PDF [PDF – 21 pages]

- Order hard copies for your office.

- Online version (replaces the app)

Learning Tools

Videos

Recognizing Lyme Carditis

CDC Expert Commentary, January 2014

Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness — When a Bull's-Eye Rash Isn't Lyme Disease

CDC Expert Commentary, March 2013

PCR for Diagnosis of Lyme Disease: Is It Useful? An update on testing for Lyme disease is provided in this commentary from the CDC.

CDC Expert Commentary, June 2012

Two-tier testing for Lyme disease

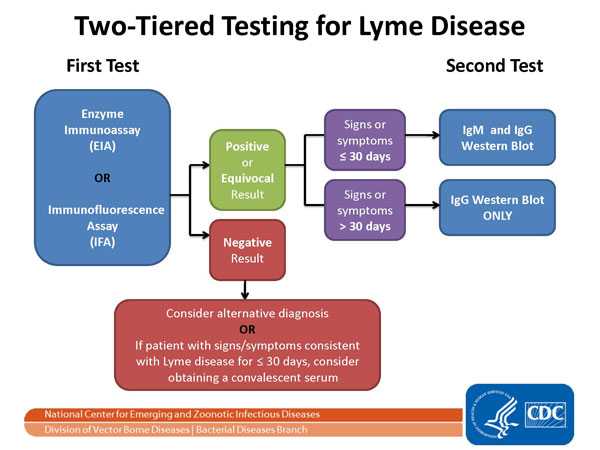

About This Figure

The Two-tier Testing Decision Tree describes the steps required to properly test for Lyme disease. The first required test is the Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) or Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA). If this test yields negative results, the provider should consider an alternative diagnosis. Or in cases where the patient has had symptoms for less than or equal to 30 days, the provider may treat the patient and follow up with a convalescent serum. If the first test yields positive or equivocal results, two options are available: 1) if the patient has had symptoms for less than or equal to 30 days, an IgM Western Blot is performed; 2) if the patient has had symptoms for more than 30 days, the IgG Western Blot is performed. The IgM should not be used if the patient has been ill for more than 30 days.

Understanding laboratory test results

About This Figure

Understanding Test Results for Infectious Diseases

The illustration depicts the likelihood of false positive and false negative test results based on the prior probability of a disease occurring in a given population. Clinicians should consider the likelihood of disease before performing laboratory testing. The likelihood that a patient has a disease depends on many factors:

- Has a patient been in an area where the disease is found?

- Does the patient have signs and symptoms typical of the disease?

- Does the patient have risk factors for contracting or developing the disease?

In populations where disease is rare or unlikely, testing is likely to lead to false positives more frequently than true positives.

Continuing Medical Education for Clinicians

- A free, CDC-sponsored Clinician Outreach and Communication Activity (COCA) course helps providers learn to properly identify and treat tickborne diseases (CME/CNE/CECH available): Little Bite, Big Disease: Recognizing and Managing Tickborne Illnesses.

- As a service to clinicians, CDC has supported the development of an online CME Case Study Course on the Clinical Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention of Lyme Disease. This free, interactive course consists of a series of case studies designed to educate clinicians regarding the proper diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. Each case is accredited for 0.25 CME credits, for a maximum of 1.5 CME. There is no cost for these credits.

- The National Association of School Nurses presents an online course titled “Tick-borne Illness: Prevention, Assessment and Care” that focuses on clinical care of tickborne diseases in school and camp settings. CNE is available.

Case Definition and Report Forms

- Lyme Disease Surveillance Case Definition (revised Jan 2017)

- Lyme Disease Surveillance Case Report Form [PDF – 2 pages] (for public health officials’ use)

Note: Surveillance case definitions establish uniform criteria for disease reporting and should not be used as the sole criteria for establishing clinical diagnoses, determining the standard of care necessary for a particular patient, setting guidelines for quality assurance, or providing standards for reimbursement.

Additional Reading

General

Halperin JJ, Baker P, Wormser GP. Common misconceptions about Lyme disease. Am J Med 2013;126(3):264.

Hu LT. Lyme Disease. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:ITC2-1.

Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 2012;379(9814):461-73.

Lyme Carditis

Forrester JD, Mead P. Third-degree heart block associated with lyme carditis: Review of published cases. Clin Infect Dis 2014 May 30. pii: ciu411.

Three Sudden Cardiac Deaths Associated with Lyme Carditis — United States, November 2012–July 2013. MMWR Dec 13;62(49):993-6.

Pediatrics and Pregnancy

American Academy of Pediatrics. Lyme disease (Lyme borreliosis, Borrelia burgdorferi infection). In: Pickering LK, Red Book: 2012

Feder HM Jr. Lyme disease in children. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2008 Jun;22(2):315-26, vii.

Walsh CA, Mayer EW, Baxi LV. Treatment of Lyme disease. Lyme disease in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2007 Jan;62(1):41-50.

Testing

Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Wang G, Schwartz I, Wormser GP. Diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005 Jul;18(3):484-509.

Branda JA, Strle F, Strle K, Sikand N, Ferraro MJ, Steere AC. Performance of United States serologic assays in the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis acquired in Europe. Clin Infect Dis 2013 Aug;57(3):333-40.

Concerns regarding a new culture method for Borrelia burgdorferi not approved for the diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR 2014;63:333.

Hinckley AF, Connally NP, Meek JI, Johnson BJ, Kemperman MM, Feldman KA, White JL, Mead PS. Lyme disease testing by large commercial laboratories in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2014 May 30. pii: ciu397.

Johnson BJ, Pilgard MA, Russell TM. Assessment of new culture method for detection of Borrelia species from serum of Lyme disease patients. J Clin Microbiol 2014;52:721–4.

Notice to readers: caution regarding testing for Lyme disease. MMWR, CDC Surveillance Summary 2005;54:125.

Johnson, B.J. “Chapter 4: Laboratory diagnostic testing for Borrelia burgdorferi infection” in Lyme disease: An Evidence-based Approach, J.J. Halperin, Ed. (CAB International, 2011). Complete Article Reproduced with Permission[PDF – 16 pages].

Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the second national conference on serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR 1995;44:590–591.

Swanson SJ, Neitzel D, Reed KD, Belongia EA. Coinfections acquired from Ixodes ticks. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006 Oct;19(4):708-27.

Treatment

Practice guidelines for the treatment of Lyme disease. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:1089-1134.

Klempner MS, Hu LT, Evans J, Schmid CH, Johnson GM, Trevino RP, Norton D, Levy L, Wall D, McCall J, Kosinski M, Weinstein A. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. New Eng. J. Med. 345:85-92, 2001.

Krupp LB, Hyman LG, Grimson R, Coyle PK, Melville P, Ahnn S, Dattwyler R, Chandler B. Study and treatment of post Lyme disease (STOP-LD): a randomized double masked clinical trial. Neurology 2003 Jun 24;60(12):1923-30.

Fallon BA, Keilp JG, Corbera KM, Petkova E, Britton CB, Dwyer E, Slavov I, Cheng J, Dobkin J, Nelson DR, Sackeim HA. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of repeated IV antibiotic therapy for Lyme encephalopathy. Neurology 2008 Mar 25;70(13):992-1003.

Schoen RT. A case revealing the natural history of untreated Lyme disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011 Mar;7(3):179-84.

Inappropriate Treatment

Ettestad PJ, Campbell GL, Welbel SF, et al. Biliary complications in the treatment of unsubstantiated Lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:356–361.

Holzbauer SM, Kemperman MM, Lynfield R. Death due to community-associated Clostridium difficile in a woman receiving prolonged antibiotic therapy for suspected Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:369–370.

Nelson C, Elmendorf S, Mead P. Neoplasms misdiagnosed as “chronic Lyme disease”. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175: 132–133. 36.

Patel R, Grogg KL, Edwards WD, Wright AJ, Schwenk NM. Death from inappropriate therapy for Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(4):1107-9.

Ongoing Research

ClinicalTrials.gov Studies of Lyme disease / “Borrelia Infections”.

Search the Biomedical Literature

PubMed, a service of the National Library of Medicine, includes over 15 million citations for biomedical articles back to the 1950's. These citations are from MEDLINE and additional life science journals. PubMed includes links to many sites providing full text articles and other related resources.

Notice: You are leaving the CDC website. We have provided a link to this site because it has information that may be of interest to you. CDC does not necessarily endorse the views or information presented on this site. Furthermore, CDC does not endorse any commercial products or information that may be presented or advertised on the site that is about to be displayed.

- Page last reviewed: March 4, 2015

- Page last updated: August 18, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir