Tracking antibiotic resistance in dangerous bacteria that affect people and cattle

CDC estimates that Salmonella bacteria cause 1.2 million illnesses in the United States every year. Most people get better quickly, but the outcome can be worse for those infected with Salmonella Dublin, a type of Salmonella usually found in cattle. Salmonella Dublin can cause serious disease in cattle, especially calves, and kill many cattle in infected herds. People can get Salmonella Dublin infections by consuming raw milk or undercooked beef, or from contact with cattle or areas where they live and roam. People with Salmonella Dublin infections have longer hospital stays, more bloodstream infections, and are more likely to die than people infected with other kinds of Salmonella. Salmonella Dublin is often resistant to antibiotics, making infections difficult to treat.

CDC investigators use data from the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS), a public health surveillance system, to track cases of resistant Salmonella Dublin in people and in animals. NARMS collects antibiotic resistance data on bacteria from people, food animals (animals used for food), and certain types of meat, and it uses this information to track trends in antibiotic resistance. CDC, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture work together on NARMS.

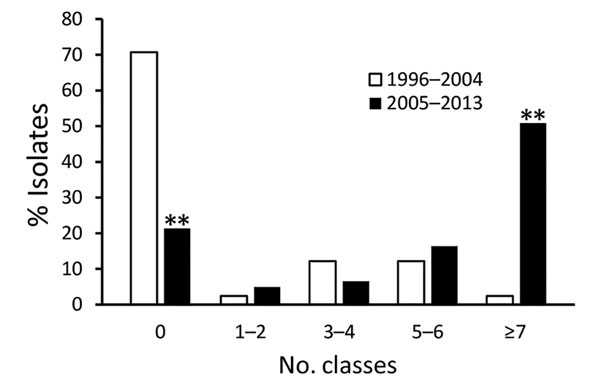

Number of classes of antimicrobial drugs to which Salmonella enterica serotype Dublin isolates were resistant

NARMS data are helping refine understanding about increasing antibiotic resistance in Salmonella Dublin. A recently published analysis of NARMS data showed that Salmonella Dublin is resistant to many classes of antibiotics, and the number of people who get these resistant infections is going up. This means that antibiotics recommended to treat Salmonella infections may not work against Salmonella Dublin infections. Results showed that from 1996 to 2013, slightly more than half (55%) of Salmonella Dublin bacteria samples from ill people were resistant to three or more classes of antibiotics. In comparison, just 1 out of every 8 (12%) of other types of Salmonella showed similar resistance. Antibiotic-resistant infections like Salmonella Dublin can continue to spread in people and animals unless control measures on farms and in food production and preparation are put in place.

Although Salmonella Dublin infections are not as common as infections with other types of Salmonella, the increasing resistance to antibiotics makes it a threat to the public’s health that requires immediate attention. By looking for antibiotic resistance in people, food animals, and meat, NARMS contributes data that can help shape antibiotic use guidelines and agricultural best practices to reduce antibiotic-resistant infections in food animals and people. For example, the FDA’s Veterinary Feed Directive aims to stop the use of antibiotics to promote growth in food animals if those antibiotics are considered medically important in humans. If antibiotics are given to people or animals who don’t require them for medical reasons, it, unfortunately, helps bacteria become resistant to antibiotics. The Directive also aims to bring other use of these antibiotics in food animals’ feed and water under the supervision of veterinarians. This careful and responsible use can help protect the public’s health by helping to keep new antibiotic resistance from developing and preventing the resistance that already exists from spreading.

More Information

- Page last reviewed: August 2, 2017

- Page last updated: August 18, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir