Volunteer Fire Chief Killed When Rubber-Tracked Vehicle Overturns at Brush Fire Washington

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

Death in the Line of Duty...A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation

F2010-15 Date Released: January 3, 2011

Executive Summary

On June 23, 2010, a 46-year-old male volunteer Fire Chief (the victim) was killed when the rubber-tracked vehicle he was operating overturned during fire suppression operations at a brush fire. The incident occurred on a steep hillside covered with sage brush and short dry grass. The victim was accompanied on the rubber-tracked vehicle by another fire fighter who was using the vehicles 1-inch hand line to knock down hot spots along the flame front. Traveling uphill, the crew encountered rocky terrain where the slope increased sharply. The vehicle lost traction on loose rocks that were thrown out from under the spinning tracks. The Fire Chief maneuvered the vehicle side-hill to the east to get through the rock outcropping. The vehicle turned uphill, lost traction again, quickly turned back to the west, and then overturned sideways and rolled downhill. The fire fighter was ejected following the first roll and was not seriously injured. The vehicle rolled at least 3 times before coming to rest on the drivers side, facing west, pinning the Fire Chief beneath the vehicles canopy. The Fire Chief died on the scene. Recovery efforts took several hours to stabilize and upright the vehicle.

|

1960s vintage vehicle was obtained by the fire department in 2008 through the states surplus fire fighter property program. |

Contributing Factors

- Limited experience operating the rubber-tracked vehicle

- Operating the vehicle in loose rock on steep terrain

- Operating the vehicle in conditions beyond the vehicles capability

- Seat belts were not used.

Key Recommendations

- Ensure that all vehicles are safe and suitable for their intended use

- Ensure that all vehicle retrofits are completed by a qualified source and that retrofits are designed and installed within the original manufacturers specifications

- Provide training on the safe operation of specialized vehicles

- Ensure that seat belts are properly worn at all times

- Be aware of programs that provide assistance in obtaining alternative funding, such as grant funding, to replace or purchase fire apparatus and equipment.

|

Rocky terrain where vehicle lost traction and overturned. Light-colored area in center of photo is where the vehicle lost traction and the tracks spun on loose rocks and soil before overturning. The overturned vehicle is seen in the top right hand corner of the photo. |

Introduction

On June 23, 2010, a 46-year-old male volunteer Fire Chief (the victim) was killed when the rubber-tracked vehicle he was operating overturned on steep rocky terrain during fire suppression operations at a brush fire. On June 24, 2010, the U.S. Fire Administration notified the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Division of Safety Research, Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program (FFFIPP) of the incident. That same day, the fire department was contacted by NIOSH investigators to initiate an investigation. On July 7, 2010, a safety engineer and an occupational health and safety specialist with the NIOSH FFFIPP traveled to Washington to investigate the fatality. The NIOSH investigators met with the interim Fire Chief and one of the three Fire Commissioners who oversee the volunteer fire department. The NIOSH investigators also met with the Fire Chief of the combination department that had incident command over the brush fire. Fire fighters who were on-scene and directly involved in the incident were interviewed. The NIOSH investigators visited the incident site and took photographs and measurements. The NIOSH investigators reviewed the fire departments standard operating procedures and the victims training records. The NIOSH investigators met with the Assistant Fire Marshal for a neighboring career department who was conducting an independent investigation for the victims fire department and obtained additional information and photographs. The NIOSH investigators reviewed a copy of the local Deputy Sheriffs Report on the incident, additional photographs and the victims death certificate. The NIOSH investigators examined the rubber-tracked vehicle involved in the incident which was being stored in a secure location.

Fire Department

The volunteer fire department involved in this incident operates as one of five fire protection districts within the county located in south-central Washington. The fire department has 30 volunteer fire fighters and operates 3 stations with a total of 10 apparatus including 6 brush trucks, 3 Class A pumpers and 1 water tender. The volunteer fire department serves a rural population of approximately 800 within an area of about 150 square miles consisting of a mixture of agricultural / farm lands, wildlands and small rural communities. The fire department provides fire fighting services and responds to an average of less than 100 calls per year. The fire department does not provide emergency medical services. The fire department is rated as a Class 8 department by ISO.a In the ISO rating system, Class 1 represents exemplary fire protection, and Class 10 indicates that the area's fire-suppression program does not meet ISO's minimum criteria.

The fire department had been working to update written policies and procedures over the past couple of years. At the time of the incident, the fire department was in the process of developing a new safety manual by modifying a neighboring fire departments safety manual to address their own needs. The safety manual contained sections covering health and safety policies, personal protective equipment and clothing, emergency medical protection, hazardous chemical protection, respiratory protection, fire apparatus, special operations, fireground operations, fire service equipment, facilities, training, and wildland fire fighting. The manual contained a section on seat belt use requiring a vehicle operator to ensure all occupants are seated with seat belts secured before putting the vehicle in motion. Chapter 6 of the fire department safety manual, section 2.3 states drivers of fire apparatus shall not move fire department vehicles until all persons are seated and secured with seat belts or safety harness in approved riding positions. Section 2.9 states before any member or employee drives or operates department apparatus they shall have successfully completed a departments drivers training program approved by the Chief.

In 2009, the fire department began to document all fire responses with a written incident after-action review form. In April 2010, the fire department implemented an after-action review process to review and discuss incident responses as a training and learning tool. After-action review reports contained subjects such as incident command, fire safety, communication, equipment placement, and use of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). After-action review reports examined by NIOSH investigators did not include reference to the rubber-tracked vehicle involved in this incident or reference to seat belt use.

aThe Insurances Services Organization (ISO) is an independent commercial enterprise which helps customers identify and mitigate risk. ISO can provide communities with information on fire protection, water systems, other critical infrastructure, building codes, and natural and man-made catastrophes. ISOs Public Protection Criteria program evaluates communities according to a uniform set of criteria known as the Fire Suppression Rating Schedule (FSRS). More information about ISO and their Fire Suppression Rating Schedule can be found at the website http://www.isogov.com/about/.

Regulations and Guidelines

The State of Washington Administrative Code (WAC), Chapter 296-305 WAC, is considered the fire fighter safety standard for the state of Washington.1 Section 296-305-07019 WAC, Training for Wildland Firefighting, states that suppression personnel assigned to a wildland fire shall be trained to the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG)b Firefighter level II or a comparable class of training with "comparable" training determined by the employer.

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards do not address the use of rubber-tracked vehicles for fire fighting applications. NFPA 1901 Standard for Automotive Fire Apparatus,2 NFPA 1906 Standard for Wildland Fire Apparatus,3 and NFPA 1912 Standard for Fire Apparatus Refurbishing,4 address vehicles designed for fire fighting applications. These standards apply to vehicles capable of meeting federal highway vehicle safety standards. Vehicles designed and intended for off-road use are excluded from NFPA fire apparatus standards. NFPA 1906, chapter 3.3.65 defines an off-road use vehicle as a vehicle designed to be used on other than paved or improved roads, especially in areas where no roads, poor roads, and steep grades exist and where natural hazards, such as rocks, stumps, and logs, protrude from the ground. NFPA 1906, chapter 3.3.93 defines a wildland fire apparatus as a fire apparatus designed for fighting wildland fires that is equipped with a pump having a capacity normally between 10 gpm and 500 gpm (38 L/min and 1900 L/min), a water tank, limited hose and equipment, and that has pump-and-roll capability.

The NWCG, as well as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), through the National Incident Management System (NIMS), Incident Command System (ICS) have adopted systems to assign a type rating to various firefighting apparatus.5, 6 Both systems define minimum requirements for national mobilization of firefighting resources. Within the typing systems, each engine type differs in levels of staffing, pump performance, tank capacity and other features. Type 1 and 2 engines are primarily used for structural fire fighting. Type 3 engines are used primarily for wildland fire fighting but can also be used for structural firefighting.c Type 4 through Type 7 engines are used primarily for wildland fire fighting. The minimum NWCG requirements for a Type 6 engine include a fire pump rated at 50 gpm (at 100 psi) and a water tank of 150 gallons. The minimum NWCG requirements for a Type 7 engine include a fire pump rated at 10 gpm (at 100 psi) and a 50 gallon tank. Type 7 engines are usually considered patrol or fire prevention vehicles and are typically configured as a pickup or platform body light duty truck with a slip-on fire package which includes a fire pump, tank, etc. The NWCG typing requirements are intended to apply to vehicles meeting federal, state, and agency requirements for motor vehicle safety standards, including all gross vehicle weight ratings when fully loaded.

The US Forest Service Handbook FSH 6709.11 Health and Safety Code Handbook7 covers health and safety guidelines and procedures for Forest Service employees. This handbook does not specifically limit the use of rubber-tracked vehicles, but Section 13.53.10 does state Do not attempt major modifications of a snow cat without the manufacturers written approval.

The US Forest Service and other federal land management agencies follow the NWCG qualification system. The NWCG National Interagency Incident Management System Wildland Fire Qualification System Guide, PMS 310-1, establishes minimum requirements for training, experience, physical fitness level, and currency standards for wildland fire positions which all NWCG-participating agencies have agreed to meet for national mobilization.8 Proof of qualification is normally an incident qualification card, commonly referred to as a red card. The NWCG recognizes the ability of cooperating agencies at the local level to jointly define and accept each others qualifications.

The State of Washington WAC 296-305 requires RED CARD certification for fire fighters engaged in wildland fire fighting activities.

bThe National Wildfire Coordinating Group is an operational group which coordinates programs of the participating wildland fire management agencies and is comprised of representatives of the US Forest Service, four Department of Interior agencies (Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs and the US Fish and Wildlife Service), the Intertribal Timber Council, 50 state forestry agencies and Puerto Rico (through the National Association of State Foresters), the US Fire Administration and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). http://www.nwcg.gov/

cThe draft FEMA typed resource definitions mirror the NWCG typing requirements for engine types 3 through 7 and tactical water tenders.

Training and Experience

The fire department requires 6 hours of basic fire fighter training for an individual to become an active member. At the time of the incident, the fire department, under the leadership of the victim, was in the process of updating and enhancing its training requirements including having members attend structural fire fighting training at a state fire training academy. A review of the fire departments training records indicated members were trained on structural fire fighting activities such as preplanning for truck deployment, self-contained breathing apparatus use, hose placement, fire size-up, escape procedures, first aid, cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR), truck maintenance, driver training, weapons of mass destruction, ladder safety, radio procedures and wildland fire protective gear. Members were also encouraged to attend wildland fire fighting classes to receive a RED CARD indicating they were qualified for wildland fire suppression activities to meet NWCG training requirements.

The victim had been a volunteer fire fighter for 28 years and had been Fire Chief of the department for 7 years. He had attended numerous fire fighter training classes in subjects such as National Incident Management System (NIMS) IS-100 and IS-700, structural fire fighting, emergency vehicle accident prevention, first aid, and CPR. Training specific to wildland fire fighting included wildland fire fighter (S-130), wildland fire behavior (S-190), crew boss (S-230), engine boss (S-231), ignition operations (S-234), task force / strike team leader (S-330), and wildland fire fighter refresher training. The Fire Chiefs training met the requirements of WAC 296-305. The injured fire fighter had received similar documented training.

Fire department records did not mention any type of formal training on the operation and use of the rubber-tracked vehicle. At the time of the incident, the Fire Chief was the only fire fighter authorized to operate the vehicle. It was reported to NIOSH investigators that the Fire Chief was in the process of training a second fire fighter to operate the vehicle. The vehicle had been used a limited number of times at brush fires since being placed into service in April 2009. Fire department members estimated that it had been used 12 times or less prior to the incident. Fire fighters interviewed by NIOSH estimated that the terrain involved the day of the incident was as steep, or steeper, than any terrain the vehicle had been operated in. The injured fire fighter, who was riding in the vehicle at the time of the incident, was frequently requested by the Fire Chief to assist on the vehicle operating the pump and hoseline(s) while the Fire Chief operated the vehicle.

There are a limited number of specialized training programs covering the safe operation of rubber-tracked vehicles of this type. Information on one such example can be found at the website http://safetyoneinc.com/fall-protection-training/. (Link updated 8/13/2013)

Equipment and Personnel

The vehicle involved in this incident was a 1960s vintage rubber-tracked off-road vehicle designed for operation in snow, mud and rough-terrain environments. The vehicles manufacturer has been out of business since the 1980s. Due to the utility of this type of vehicle, there is a well-established secondary market for used vehicles of this model as well as other manufacturers models. The vehicle was originally designed with an enclosed cab equipped with two side-by-side bucket seats separated by the engine and transmission housing (see Photo 1 and Photo 2). The vehicle was powered by a 4-cylinder, 30 horsepower, 107.7 cubic-inch gasoline engine. The drive train included a manual transmission (4-speed forward and 1-speed reverse) equipped with a hand-controlled pressure clutch and a rear-mounted planetary differential drive. The vehicle was steered by manipulating two floor-mounted hydraulically-operated steering levers that manipulated the differential drive. Shifting gears required a two-handed operation one to engage the clutch lever and one to manipulate the gear shift lever, thus the operator did not have control over the steering levers while shifting gears. The vehicle was operated from the left seat position. Both seats included lap-style seat belts (see Photo 2).

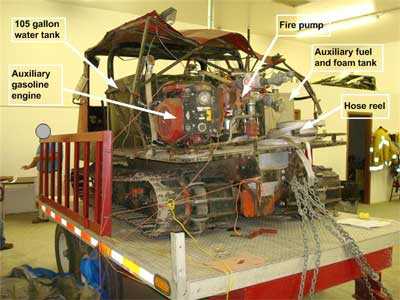

The vehicle was obtained by the fire department in 2008 through the states surplus vehicle exchange program. It is believed that the vehicle was previously used by the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Forest Service. The vehicle was reportedly retrofitted by the departments Fire Chief (the victim) for use as a wildland fire vehicle for mobile attack with pump and roll capability (meaning the ability to pump water while moving). The retrofits included the addition of extra lighting and rear-view mirrors, an auxiliary gasoline engine-powered fire pump, a pump control panel, a 105-gallon steel fuel tank used as a water reservoir, a two-compartment stainless steel tank used for gasoline and class-A foam solution, a 1-inch red brush hose, sections of 1 ¾-inch hose stored on a horizontal hose reel, and various fire suppression tools (see Photo 3). A roll bar system was added inside the cab. The vehicle originally included windows, window wipers, headlights and doors but the doors, all windows, and wipers had been removed at some point prior to the incident. It is not known who removed the doors and windows. There were no records covering the operation, maintenance or retrofitting of the rubber tracked vehicle.

|

|

Photo 1 (left) and Photo 2 (right). Views of rubber-tracked vehicle showing operators seat. In Photo 1, the vehicle is setting on the departments trailer inside a secure location. Photo 2 shows a close-up view of the interior of the cab and the bucket seats equipped with seat belts. |

|

Timeline

The timeline for this incident is limited to the initial report of a possible brush fire, the victims response to the fire, and the events leading up to the fatal rollover. Times are approximate and have been rounded to the nearest minute.

- 1430 Hours

Combination fire department observes smoke in the area where the incident occurred and calls dispatch to inquire about controlled burns in the area - 1448 Hours

Combination fire department dispatched for wildland fire - 1511 Hours

Combination fire department on scene; chief establishes incident command - 1515 Hours

Chief of Volunteer Fire Department (Victim) calls the Incident Commander (IC) and asks if mutual aid is needed. IC replies - yes. - 1615 Hours

Vehicle rollover reported to the IC - 2210 Hours

Victim transported from area

Personal Protective Equipment

At the time of the incident, both the victim and the injured fire fighter were wearing wildland fire suppression personal protective clothing including pants, coat, helmet, goggles, gloves and boots. The victim had a radio equipped with a head-set. Personal fire shelters were available. Fire shelters were stored on all fire apparatus.

|

Photo 3. View of equipment added to the rear of the rubber-tracked vehicle, showing the 105-gallon water tank, auxiliary gasoline engine, hose storage reel, auxiliary fuel and foam tank, and fire pump. |

Weather Conditions and Terrain

At the time of the incident, the weather was overcast with an approximate temperature of 87°F and relative humidity of 27 percent. Northwest winds were reported at approximately 5 8 miles per hour.9 The weather had been dry for several days and this time of year was considered the active wildland fire season.

The incident occurred on a sloped hillside covered with sage brush and short dry grass at an elevation of approximately 1,510 feet above sea level. Rough measurements at the incident site indicated the hillside slope to be approximately 55 degrees. A commercial orchard was located at the bottom of the hill and approximately 400 yards south of the incident site (see Photo 4 through Photo 8).

|

|

|

|

|

Photo 7. Photo looking downslope from the point where vehicle overturned to the vehicles final resting place. Debris field is visible along path of rollover. Note the size and shape of loose rocks. Dark areas to the left are where the fire burned and the lighter colored areas at the bottom of the photo are where the vehicles tracks spun on the loose rock and soil. |

|

|

Photo 8. Photo looking downhill to the vehicles final resting place. Tracks are visible where a brush truck backed up hill to lay down wet line to stop westward spread of fire. Loose rocks on the outcropping are visible at the lower left corner of photo.

|

Investigation

At approximately 1448 hours, the local combination fire department was dispatched to a wildland fire. The Fire Chief, a captain, and four fire fighters responded in three brush trucks to the incident scene. While enroute, the Chief of the combination department requested mutual aid from district # 8 and also requested dispatch to notify the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service since the fire was in close proximity to a national wildlife refuge.

The crews from the combination fire department arrived on scene and the Chief established incident command. The fire originated in a pit where PVC pipe and other refuse materials were being burned by employees from the neighboring commercial orchard. The orchard employees attempted to control the fire with shovels and a small orchard sprayer before calling 911. After sizing up the incident scene, the Incident Commander (IC) radioed dispatch and requested additional resources. A single engine air tanker (SEAT) was also dispatched. The Fire Chief (the victim) from a volunteer fire department (district # 4) in the adjacent county called the IC via cell phone and asked if mutual aid was needed. The IC replied yes and the district # 4 mutual aid department was dispatched.

The fire spread up a ravine and then burned around the hillside from east to west, growing to over 20 acres in size. The IC divided the fire suppression operations into two divisions, east and west, and established an incident command post at the east end of the fire.

A dirt road at the northern edge of the orchard provided access for fire crews to advance to the west and position in front of the fire. Two brush trucks were backed up the hill to the point where the slope of the hill increased significantly and waited for the fire to advance closer, then spread water downhill to the access road, creating a wet line which slowed the fire spread. The SEAT aircraft arrived and dropped water further up the hill in an area the brush trucks could not access. The SEAT was successful in slowing the fire spread in that area but did not completely extinguish the fire and crews on foot began mopping up hot spots along the fire front. The district # 4 Fire Chief (the victim) and three fire fighters arrived in two fire department vehicles with one towing the rubber-tracked vehicle on a trailer. The district # 4 crew was directed to report to the west division to assist with mop-up operations.

The crews working the west division were successful in stopping the fire at the wet line but hot spots further up the hill began to re-kindle and the fire began spreading westward further up the hill. The district # 4 Fire Chief (victim) unloaded the rubber-tracked vehicle and discussed the incident with fire fighters already on-scene. Two district # 4 fire fighters moved uphill on-foot to assist with mop-up activities along the fire line and the third district # 4 fire fighter accompanied the victim on the rubber-tracked vehicle. The vehicle proceeded straight up the hill west of the fire line to approximately 40 feet from where the fire had rekindled. The fire fighter hit hot spots with four quick bursts of water from the 1-inch hoseline on the vehicle. As they continued to climb uphill, they encountered an area of loose exposed rocks. Many of the rocks were roughly round or oval shaped and varied in size from approximately 6 inches to approximately 12 inches or more (see Photo 7 and Photo 8). The slope of the hill also increased significantly at and above the rock outcropping. While crossing the area of exposed rock, the tracked vehicle began to lose traction and spin, causing the loose rocks to roll out from underneath the tracks. Witnesses reported that the vehicle inched forward, then slid backward down the hill several feet, before regaining traction and continuing uphill. The vehicle turned to the east (drivers side uphill) and proceeded to travel side hill across the rock outcropping. After advancing around the hill a short distance the vehicle again turned north to climb higher up the hill. The vehicle lost traction again as loose rocks rolled out from under the tracks. As the tracks continued to spin in the loose rocks, the vehicle suddenly jerked, spun around facing to the left (west) with the drivers side downhill, then tipped toward the drivers side and began rolling sideways down the hill. The fire fighter was thrown out of the vehicle after the first roll. The vehicle rolled at least three times, over a distance of approximately 100 feet, and came to rest on the drivers side with the front end facing west.

Fire fighters working the fire line below the vehicle immediately ran toward the overturned vehicle. They found the vehicles cab resting on the victims head and neck. The fire fighters attempted to push the vehicle off of the victim but could not, so they quickly dug out beneath the victims head to relieve the pressure caused by the weight of the vehicle. The IC was immediately notified of the rollover and dispatch was notified that a medical helicopter was needed. Shortly thereafter, the medical helicopter was cancelled after rescuers working to free the victim failed to detect a pulse. The victim died on the scene. Recovery efforts took several hours to stabilize and upright the vehicle. The victim was transported from the area at approximately 2210 hours.

Seat Belt Use

Both seats in the vehicle were equipped with lap-style seat belts. Photos taken by the sheriffs office investigators showed that the victim was not wearing his seat belt at the time of the incident. The injured fire fighter advised the NIOSH investigators that he was not wearing his seat belt during the incident.

Vehicle Examination

On July 7, 2010, NIOSH investigators examined the vehicle which was stored in a secure location. The vehicle was setting on the fire departments flatbed trailer and was reported to have been secured since being transported following recovery operations the night of the incident. Photographs and measurements of the vehicle were taken. While a detailed mechanical and forensic evaluation of the vehicle was outside the scope of this investigation, it is believed that the combination of the weight of the retrofitted equipment and the weight of the two fire fighters exceeded the vehicles rated payload capacity of 1400 pounds (the combined weight of all occupants, equipment, materials and/or supplies carried on the vehicle). Adding additional weight above the recommended payload may have adversely shifted the vehicles center of gravity, resulting in stability issues as the vehicle traversed steep terrain. A technical spec sheet for the same or similar model vehicle was located on the internet.10, 11

During the vehicle examination, it was noted that the right steering lever and the clutch handle were both broken off, probably during the rollover event (see Photo 9 and Photo 10). Other damage included damage to the canopy and to the left track mechanism. The injured fire fighter told NIOSH investigators that it did not appear that there were any mechanical problems with the vehicle prior to the rollover and the victim did not mention any problems prior to the rollover. The injured fire fighter did indicate that verbal communication was difficult due to the sound generated by the vehicle.

The total weight of the vehicle at the time of the incident is unknown. The available vehicle spec sheets10, 11 list an empty weight of 1900 pounds. At some point (undetermined in this investigation), the vehicles doors, windows and miscellaneous equipment (windshield wipers, etc) were removed. The fire department added extra lights, mirrors, a roll-bar and a variety of fire suppression equipment including a steel water tank (originally designed and produced for use as a diesel fuel tank), a two-compartment steel tank used as a fuel tank for the auxiliary fire pump and as a storage tank for class A foam solution, a gasoline engine-powered fire pump, hose storage reel, multiple fire hoses, and a variety of hand tools for wildland fire suppression activities. Note: The fuel tank (used as a water tank) contained steel plates inside the tank mounted at the top and bottom near the center and perpendicular to the tanks long axis. These plates were likely included as reinforcing plates and did not appear to meet the requirements specified in NFPA 1906, Chapter 11 for water tank baffles.3 A rough estimate shows that just the weight of the water and gasoline in the auxiliary tanks plus the estimated weight of the two fire fighters on the vehicle likely exceeded the rated 1400 pound payload.

Table 1 Estimated partial payload weight

| 105 gallons water | 876.3 pounds (8.3453 lbs/gallon) |

| 21 gallons gasoline | 124.5 pounds (5.93 lbs /gallon)d |

| 2 fire fighters (victim and injured occupant) | 540 pounds e |

| Estimated Partial payload | 1540 pounds |

|

Rated payload

|

1400 pounds |

The combined weight of the fire pump and gasoline motor, hoses, hose reel, foam solution and hand tools likely added several hundred more pounds of cargo weight. It is likely that the weight of the vehicle could have exceeded the rated payload by several hundred pounds. Note: the exact weight of the payload is unknown, including the volume of water in the auxiliary tank at the time of the incident. The injured fire fighter reported flowing a small amount of water (four quick bursts from the hoseline) on spot fires prior to the roll-over. Witnesses reported both water and fuel leaking from the vehicle after it overturned. The only way to know whether the vehicle was overloaded would have been to weigh the vehicle after the incident.

Additional weight added to the back of the vehicle would have the potential to raise the center of gravity above the original center of gravity, reducing the vehicles stability. It is difficult to know for certain whether issues with the vehicles center of gravity were a contributing factor in this incident. The water tank was mounted directly behind the operators seat and was not centered over the vehicles long axis. The auxiliary gasoline engine and fire pump were mounted near the rear end of the vehicles bed (see Photo 3). In addition to the possibility that the added equipment raised the center of gravity, the asymmetrical mounting location of the water tank likely shifted the center of gravity to the drivers side, which was on the downhill side preceding the rollover. The water (in the tank) comprised approximately 25 percent of the total vehicle weight (weight of water divided by the vehicles empty weight plus estimated partial payload). Water tanks are usually installed as low as possible, centered along the fire vehicles long axis to minimize asymmetrical loading and shifting of the vehicles center of gravity. Appendix 1 contains additional information including center of gravity estimations for rubber-tracked vehicles similar to the one involved in this incident.

Off-road Operation Safety Considerations

Knowing the capability of your vehicle is a prime consideration for all vehicle operators but is especially important in off-road operation. The hillside slope where the incident occurred was roughly measured at 55 degrees (142.8 percent slope). For comparison, the NFPA 1906 Standard for Wildland Fire Apparatus requires fire department vehicles to remain stable on a slope of 30 degrees during a tilt-table test.3 Most vehicles have significantly less side stability than fore and aft so if there is a problem going straight up the slope, turning sideways only increases the potential for an incident. During off-road operation, if a vehicle reaches a point where it cannot progress straight up an incline, turning sideways on the incline is not an option. Any tracked vehicle using a skid-steering system that loses traction on one track will turn toward the track that is spinning. This results in the potential for the vehicle to change direction without operator interaction. This problem may be compounded in steeper terrain where stability becomes an issue.f See Appendix 1 for additional information concerning stability issues on sloped surfaces.

dThe exact weight of the gasoline in the auxiliary tank is unknown. The website http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_much_does_a_gallon_of_gasoline_weigh estimates the weight of one gallon of gasoline at 5.93 to 6.42 lbs, depending on the grade and blend of gasoline, ambient conditions and other factors.

eNFPA 1906 Standard for Wildland Fire Apparatus (2006 edition) specifies the use of 270 pounds per seating position for weight / stability calculations. The 270 pound estimate includes 200 pounds for the weight of the fire fighter and 70 pounds for personal protective equipment and clothing.

fPersonal correspondence between Roscommon Equipment Center and the report authors during external expert review of the draft report.

Contributing Factors

Occupational injuries and fatalities are often the result of one or more contributing factors or key events in a larger sequence of events that ultimately result in the injury or fatality. NIOSH investigators identified the following items as key contributing factors in this incident that ultimately led to the fatalities:

- Limited experience operating the rubber-tracked vehicle

- Operating the vehicle in loose rock on steep terrain

- Operating the vehicle in conditions beyond the vehicles capability

- Seat belts were not used.

Cause of Death

According to the death certificate, the victims cause of death was accidental due to multiple internal injuries caused by blunt impact to the head and neck. Several rib fractures were also detected.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: Fire departments should ensure vehicles are safe and suitable for their intended use.

Discussion: The vehicle involved in this incident was well suited for use in snow, mud and rough terrain environments. However, it had not been designed for use as a mobile attack fire apparatus. The vehicle was obtained by the fire department in 2008 through the states surplus vehicle program and retrofitted with various equipment and tools for use as a mobile attack engine at brush and wildland fires. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) type ratings are intended to apply to vehicles meeting federal, state and agency requirements for motor vehicle safety standards, including all gross vehicle weight ratingsg when fully loaded.5 The vehicle involved in this incident was designed as an off-road vehicle and thus is not regulated by and does not meet federal motor vehicle safety standards, since it was not designed for highway use. National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards exclude off-road vehicles because they do not meet these same federal motor vehicle safety standards.2,3,4 Fire departments should use NFPA standards such as NFPA 1500, 1901, 1906, and 1912 as guides when selecting and refurbishing vehicles before those vehicles are put into service. Such standards provide design specifications that help ensure that vehicles and equipment are safe for use in fire fighting operations. Roscommon Equipment Center12 is another source of valuable information. Roscommon develops and tests equipment for wildland fire service, specializing in the conversion of surplus military vehicles into wildland fire suppression units, including some types of tracked vehicles. Following established guidelines will help ensure vehicles are safe and suitable for their intended use.

Recommendation # 2: Fire departments should ensure that all vehicle retrofits are completed by a qualified source and that retrofits are designed and installed within the original manufacturers specifications.

Discussion: The vehicle involved in this incident was believed to have been manufactured in the mid 1960s and was designed for use in snow, mud and rough-terrain environments. The vehicle was obtained by the fire department in 2008 through the states surplus vehicle exchange program. It is believed the vehicle was previously used by the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Forest Service. The vehicle was retrofitted for use as a wildland fire vehicle for mobile attack with pump and roll capability (meaning the ability to pump water while moving). While rubber-tracked vehicles retrofitted for use in wildland fire applications are commercially available, there are no national consensus standards or guidelines for doing this type of work. NFPA 1912 Standard for Fire Apparatus Refurbishing5 excludes vehicles that are not designed for highway use and do not meet applicable federal vehicle safety standards. NFPA 1912 provides guidelines for ensuring that refurbished fire apparatus meet all applicable federal, state, and local regulations covering vehicle safety as well as the applicable NFPA standards covering fire apparatus.

It is important to understand how retrofitting vehicles can change the vehicles weight and center of gravity. The addition of extra equipment such as water tanks, pumps, hoses and tools add extra weight which can raise the vehicles center of gravity higher than when originally manufactured. A low center of gravity contributes to improved vehicle stability. Fire departments should be aware of resources such as the Roscommon Equipment Center, a cooperative program between the National Association of State Foresters and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.12 Roscommon Equipment Center develops guidelines for local, state, and federal fire agencies to safety convert vehicles to wildland fire apparatus. Fire departments should consider weighing their fully-loaded vehicles and keeping an inventory of the various equipment and tools maintained on the vehicle to help ensure that vehicles are operated within their rated capacities.

Recommendation # 3: Fire departments should provide training on the safe operation of specialized vehicles.

Discussion: Fire fighters require considerable knowledge, skills and abilities in order to properly and safely operate fire apparatus. The NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, 2007 Edition recommends in Chapter 6.2 that fire departments provide training to all operators of all types of motorized equipment they will be expected to operate.13 NFPA 1002 Standard for Fire Apparatus Driver/Operator Professional Qualifications, Chapter 5 lists the requisite knowledge and skills necessary to safely operate fire apparatus equipped with fire pumps.14 However, the rubber-tracked vehicle involved in this incident is not recognized as a fire apparatus (engine) under the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) and National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) guidelines. Prior to this incident, the victim was the only fire department member qualified to operate the vehicle. The victim was in the process of training a second fire fighter to operate the vehicle. There was no evidence that the victim had received any training on the operation and use of the vehicle, beyond his own hands-on experience. There are a limited number of specialized training programs covering the safe operation of rubber-tracked vehicles of this type. Information on one such example can be found at the website http://safetyoneinc.com/fall-protection-training/. (Link updated 8/12/2013)

Recommendation #4: Fire departments should ensure that seat belts are properly worn at all times.

Discussion: Vehicle crashes are the second leading cause of fire fighter line-of-duty deaths.15 NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program states that all persons riding in fire apparatus should be seated and belted securely by seat belts in approved riding positions at any time the vehicle is in motion, and the seat belts should not be released or loosened for any purpose while the vehicle is in motion.13 Fire departments should develop, implement and enforce standard operating procedures (SOPs) on the proper use of seat belts in accordance with NFPA standards. Numerous nationally recognized fire service entities have guidance available on implementing a seat belt policy. The International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) provides guidance in their document Standard Operating Procedures, Fire Department Vehicle Safety, Emergency and Non-Emergency Response, and Safe Emergency Operations on Roadways,16 and recommends that all employees use seat belts at all times: All personnel shall ride only in regular seats provided with seat belts. The company officer and driver of the vehicle shall confirm that all personnel and riders are on-board, properly attired, with seat belts on, before the vehicle is permitted to move. This confirmation shall require a positive response from each rider. The International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC), Guide to IAFC Model Policies and Procedures for Emergency Vehicle Safety, states that The driver shall not begin to move the vehicle until all passengers are seated and properly secured. All passengers shall remain seated and secured as long as the vehicle is in motion. Seat belts shall not be loosened or released while en route to dress or don equipment.17 The fire department involved in this incident had recently adopted a safety manual covering a number of items including seat belt use.

Recommendation #5: Fire departments should be aware of programs that provide assistance in obtaining alternative funding, such as grant funding, to replace or purchase fire apparatus and equipment.

Discussion: While it is important that fire departments seek constant improvements and upgrades to their fire apparatus and equipment, some departments may not have the resources or programs to replace or upgrade their apparatus and equipment as often as they should. Alternative funding sources, such as federal grants, are available to purchase fire apparatus and equipment. Additionally, there are organizations that can assist fire departments in researching, requesting, and writing grant applications.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Assistance to Firefighters Grant (AFG) Program

www.firegrantsupport.com

The primary goal of the Assistance to Fire Fighters Grant (AFG) Program is to provide critically needed resources such as emergency vehicles and apparatus, equipment, protective gear, training for responders, and other needs to help fire departments protect the public and emergency workers from fire and related hazards. FEMA grants are awarded to fire departments to enhance their ability to protect the public and fire service personnel from fire and related hazards. The Grant Programs Directorate of FEMA administers the grants in cooperation with the United States Fire Administration. This Web site offers resources to help fire departments prepare and submit grant requests.

National Volunteer Fire Council (NVFC), Grants & Funding

http://www.nvfc.org/hot-topics/grants-funding (Link updated 4/9/2013)

The NVFC provides an online resource center to assist departments applying for various types of fire grants, including narratives from successful past grant applications and a listing of federal grant and funding opportunities.

FireGrantsHelp.com

www.firegrantshelp.com

A nongovernmental group, FireGrantsHelp's mission is to provide firefighters and departments with a comprehensive resource for grant information and assistance. FireGrantsHelp.com provides an extensive database of information on federal, state, local, and corporate grant opportunities for first responders.

Additional resources related to staffing and training include:

FEMA, Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response (SAFER) Grants

www.firegrantsupport.com/safer/ (Link no longer available 5/13/2015)

SAFER grants provide funding directly to fire departments and volunteer firefighter interest

organizations to help them increase the number of trained, front-line fire fighters in their communities and to enhance the local fire departments’ abilities to comply with staffing, response, and operational standards established by NFPA and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), Safer Act Grant

www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/standards-development-process/safer-act-grant (Link Updated 8/13/2013)

NFPA provides excerpts from NFPA 1710 and NFPA 1720 and other online resources to assist fire departments with the grant application process.

Federal Excess Personal Property Program

www.fs.fed.us/fire/partners/fepp

The Federal Excess Personal Property Program is administered by the US Forest Service. This program refers to Forest Service-owned property that is on loan to State Foresters for the purpose of wildland and rural fire fighting. Most of the property originally belonged to the US Department of Defense. Once acquired by the Forest Service, property is loaned to State Coordinators for fire fighting purposes. State Foresters may place property with local fire departments to improve local fire programs.

Department of Defense Firefighter Program

http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/partners/fepp/DODprogram/index.html

In cooperation with the US Forest Service, excess Department of Defense equipment is made available for wildland and rural fire fighting purposes through the Federal Excess Personal Property Program.

Rural & Volunteer Fire Assistance

http://www.fs.fed.us/fire/partners/vfa/

The US Forest Service, Volunteer Fire Assistance Program (VFA), formerly known as the Rural Community Fire Protection Program (RCFPP) can provide Federal financial, technical, and other assistance to State Foresters and other appropriate officials to organize, train, and equip fire departments in rural areas and rural communities to suppress fires. A rural community is defined as having 10,000 or less population.

Recommendation #6: Standard setting organizations should consider developing driver training requirements covering the operation of off-road vehicles.

Discussion: Off-road vehicles such as all-terrain vehicles (ATV), utility vehicles (UTV), tracked vehicles, and other types of motorized vehicles designed or retrofitted for off-road use have practical utility within the fire service. Such vehicles are capable of operating in steep or rugged terrain containing obstacles such as rocks, trees, mud, snow, deep water and other hazards that vehicles designed for highway use cannot traverse. Operating off-road vehicles in these types of terrain require specialized operator training and hands-on experience in order to safely operate these types of vehicles in these conditions. The NFPA 1451 Standard for a Fire Service Vehicle Operations Training Program, 2007 Edition, details specific requirements for a fire department training program for fire service vehicle operations.18 The NFPA 1500 Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, 2007 Edition recommends in Chapter 6.2 that fire departments provide training to all operators of all types of motorized equipment they will be expected to operate.13 Both NFPA 1451 and NFPA 1500 standards place an emphasis on the safe arrival of the apparatus at the scene of the emergency as the first priority. However, the NFPA standards currently address only those vehicles that are designed for highway use and that meet federal highway vehicle safety standards. Off-road vehicles are excluded from the NFPA standards and there is little oversight for driver training requirements covering off-road vehicles. Standard setting organizations such as the NFPA should consider developing driver training requirements for off-road vehicles. The vehicle involved in this incident was a rubber-tracked vehicle designed for operation in snow, mud and rough terrain. There are a limited number of specialized training programs covering the safe operation of rubber-tracked vehicles of this type. Information on one such example can be found at the website http://safetyoneinc.com/fall-protection-training/ (Link updated 8/12/2013)

Recommendation # 7: Standard setting organizations should consider developing design and test requirements for off-road vehicles used for wildland fire suppression operations.

Discussion: As noted above, the NFPA standards only address vehicles that are designed for highway use and that meet federal highway vehicle safety standards. Off-road vehicles are excluded from the NFPA standards. Since off-road vehicles are used on a regular basis by the fire service for many different applications, the NFPA should consider developing minimum design and test requirements for off-road vehicles. Such standards would help to ensure the safety and reliability of these types of vehicles used by the fire service. The NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program has investigated a number of fire fighter line-of-duty deaths involving vehicles obtained through surplus property programs.19-25 These vehicles are often obtained at minimal cost and then modified by the fire department. In many cases, budgetary concerns dictate that the modifications are done as cost effectively as possible and with little or no oversight. Guidelines are needed to help ensure off-road vehicles are designed and certified for safe operation and use by the fire service.

gA gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) is the maximum allowable total mass of a road vehicle or trailer when loaded i.e. the weight of the vehicle itself plus the weight of all passengers, cargo, fuel and any trailer tongue weight. (source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page) (Link Updated 1/28/2013)

References

- Washington Administrative Code [1997]. Chapter 296-305: Safety Standards for Fire Fighters. http://www.lni.wa.gov/safety/rules/chapter/305/ (Link Updated 5/13/2015). Date accessed: September 13, 2010.

- NFPA [2009]. NFPA 1901: Standard for Automotive Fire Apparatus, 2009 Edition. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2006]. NFPA 1906: Standard for Wildland Fire Apparatus, 2006 Edition. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2006]. NFPA 1912: Standard for Fire Apparatus Refurbishing, 2006 Edition. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NWCG [2007]. National Mobilization Minimum Engine and Water Tender Typing. November 26, 2007. National Interagency Fire Center, Boise, ID. National Wildfire Coordinating Group. http://ross.nwcg.gov/documentslibrary/support_docs/ROSS_NWCG_Water_Tender_Reclassification_2008_0416.pdf. Date accessed: September 14, 2010. (Link Updated 5/13/2015)

- FEMA [2005]. Typed Resources Definitions. Fire and hazardous materials resources. Publication FEMA 508-4. July 2005. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency. http://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nims/fire_haz_mat.pdf. Date accessed: September 15, 2010.

- USFS [1999]. Forest Service Handbook (FSH) 6709.11. U.S. Forest Service. Washington DC. Publication number 6709.11. http://www.fs.fed.us/cgi-bin/Directives/get_dirs/fsh?6709.11. Date accessed: September 15, 2010.

- NWCG [2009]. National Interagency Incident Management System Wildland Fire Qualifications System Guide. PMS 310-1. June 2009. National Interagency Fire Center, Boise, ID. National Wildfire Coordinating Group. http://www.nwcg.gov/pms/docs/pms310-1.pdf Date accessed: November 24, 2010.

- Weather Underground [2010]. http://www.wunderground.com/history/airport/KHMS/2010/6/23/DailyHistory.html?req_city=Othello&req_state=WA&req_statename=Washington. Date accessed: September 2, 2010.

- Safety One [2010]. Snow cat manufacturer specification sheets. http://www.safetyoneinc.com/specsheets/thiokol.1402.1.html. Date accessed: October 25, 2010.

- Tahoe Basin [2010]. http://www.tahoebasin.com/snowcats/imp.htm (Link no longer available 5/13/2015). Date accessed: October 25, 2010.

- REC [2009]. Guidelines for designing wildland fire engines. Roscommon Equipment Center (REC). http://www.roscommonequipmentcenter.com. Date accessed: September 17, 2010.

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1500 Standard on fire department occupational safety and health program. 2007 ed. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2009]. NFPA 1002: Standard for Fire Apparatus Driver/Operator Professional Qualifications, 2009 Edition. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NFPA [2008]. Fire fighter fatalities in the United States—2008. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- International Association of Fire Fighters [2008]. Fire department standard operating procedure, fire department vehicle safety, emergency and non-emergency response, safety emergency operations on roadways. http://www.iaff.org/hs/evsp/Vehicle%20Safety%20SOP.pdf Date accessed: September 16, 2010.

- International Association of Fire Chiefs [2007]. Guide to IAFC model policies and procedures for emergency vehicle safety. http://www.iafc.org/files/1SAFEhealthSHS/VehclSafety_IAFCpolAndProceds.pdf. Date accessed: September 16, 2010. (Link updated 10/28/2013)

- NFPA [2007]. NFPA 1451 Standard for a Fire Service Vehicle Operations Training Program, 2007 Edition. Quincy, MA: National Fire Protection Association.

- NIOSH [2001]. Fire Fighter Dies After the Tanker Truck he was Driving Strikes a Utility Pole and Overturns while Responding to a Grass Fire Kentucky. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV. FACE Report F2001-06. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200106.html.

- NIOSH [2002]. Volunteer Fire Fighter Dies after being Run Over by Brush Truck during Grass Fire Attack - Texas. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV. FACE Report F2002-36. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200236.html.

- NIOSH [2003]. Volunteer Assistant Chief Dies in Tanker Rollover New Mexico. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV. FACE Report F2003-23. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200323.html.

- NIOSH [2004]. Forest Ranger/Fire Fighter Drowned after Catastrophic Blow-out of Right Front Tire Florida. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV. FACE Report F2004-15. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200415.html.

- NIOSH [2005]. Volunteer Fire Chief Dies from Injuries Sustained during a Tanker Rollover Utah. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV. FACE Report F2005-27. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200527.html.

- NIOSH [2006]. Volunteer Fire Fighter Dies in Tanker Rollover Crash Texas. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV. FACE Report F2006-06. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200606.html.

- NIOSH [2009]. One Fire Fighter Dies and another is Severely Injured in a Single Vehicle Rollover Crash Georgia. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Morgantown, WV. FACE Report F2009-08. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200908.html.

Investigator Information

This incident was investigated by Timothy R. Merinar, MS, CFEI, Safety Engineer, and Stacy C. Wertman, ISO, Safety and Occupational Health Specialist, with the Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, Surveillance and Field Investigations Branch, Division of Safety Research, NIOSH located in Morgantown, WV. An expert technical review was provided by David Haston, P.E., US Forest Service and Kirk Bradley, Administrator with the Roscommon Equipment Center. A technical review was also provided by the National Fire Protection Association, Public Fire Protection Division. This report was authored by Timothy R. Merinar.

Additional Information

National Wildfire Coordinating Group

- http://www.nwcg.gov/

National Wildfire Coordinating Group

National Interagency Fire Center

3833 S. Development Ave.

Boise, ID 83705

National Wildfire Coordinating Group Training and Qualifications

- http://www.nwcg.gov/

National Wildfire Coordinating Group

National Interagency Fire Center

3833 S. Development Ave.

Boise, ID 83705

Disclaimer

Mention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to Web sites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these Web sites.

|

Photo 9. Photo shows that clutch lever has broken off. The injured fire fighter, who was riding on the vehicle at the time of the rollover, did not notice any mechanical problems prior to the rollover. |

|

Photo 10. Photo shows that the right steering lever has broken off. The injured fire fighter, who was riding on the vehicle at the time of the rollover, did not notice any mechanical problems prior to the rollover.(NIOSH Photo) |

Center of Gravity Estimations

NFPA 1906, Standard for Wildland Fire Apparatus, 2006 Edition,3 Chapter 4.9.1 states that the calculated center of gravity shall be no higher than 75 percent of the rear vehicle axle track width for a vehicle with a GVWR of 33,000 lb (14,969 kg) or less or must pass a side stability tilt test of 30 degrees in each direction before any wheel lifts off the test surface. While NFPA 1906 does not specifically apply to the vehicle involved in this incident, the theory behind this part of the standard should hold true for this type of vehicle. Based on the vehicle’s overall width and the width of the track pads the vehicle’s track can be calculated. Using information from the specification sheets identified from the internet for various models of the vehicle involved in this incident,10,11 the following table lists the calculated vehicle track width, estimated maximum vertical center of gravity and the overall vehicle height of these models.

| Model | Track | Vertical CG (max) Per NFPA 1906 |

Overall Height

|

|---|---|---|---|

1402 |

48” |

36” |

66” |

1404 standard |

44.5” |

33.4” |

73.5” |

1404 wide track |

52.5” |

39.4” |

75” |

Based upon the vehicle’s 30 horsepower 4-cylinder gasoline engine, the vehicle was most likely a 1402 model. The estimated maximum vertical center of gravity for the model 1402 is at 36-inches or over ½ of the vehicle’s height. Based on this estimation, it appears that the rubber tracked vehicle equipped with the fire suppression equipment might be in compliance with the stability requirements of NPFA 1906. This is only an estimation and further testing to accurately verify the vertical center of gravity of this vehicle would have to be done to verify how the addition of the extra equipment affected the stability and how it might have factored into incident.

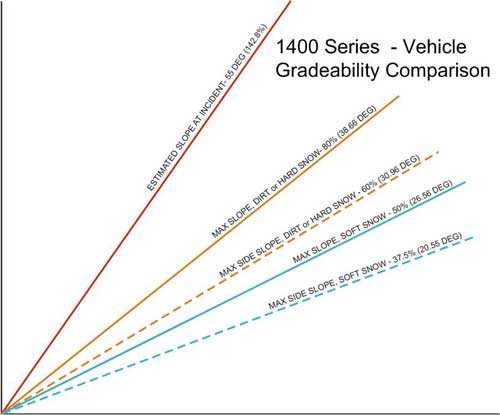

The Roscommon Equipment Center (REC) was asked to review a draft of this report. Based on the available information, REC prepared a graph that compares the manufacturer’s maximum ratings for stability of the rubber tracked vehicle on common surfaces to the slope measured at the incident scene. According to this information, the vehicle’s maximum ratings are 80% (~38.7 deg) going straight up a slope and 60% (~31 deg) on a side slope. The manufacturer’s side slope rating for this vehicle on hard dirt closely approximates the 30 deg maximum allowed under NFPA 1906. These vehicle ratings are substantially less than the slope measured at the incident site.

The graph below illustrates the difference between the slopes the vehicle was rated for and the estimated 55 degree slope of the incident site.

|

|

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), an institute within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is the federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. In 1998, Congress appropriated funds to NIOSH to conduct a fire fighter initiative that resulted in the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program which examines line-of-duty-deaths or on duty deaths of fire fighters to assist fire departments, fire fighters, the fire service and others to prevent similar fire fighter deaths in the future. The agency does not enforce compliance with State or Federal occupational safety and health standards and does not determine fault or assign blame. Participation of fire departments and individuals in NIOSH investigations is voluntary. Under its program, NIOSH investigators interview persons with knowledge of the incident who agree to be interviewed and review available records to develop a description of the conditions and circumstances leading to the death(s). Interviewees are not asked to sign sworn statements and interviews are not recorded. The agency's reports do not name the victim, the fire department or those interviewed. The NIOSH report's summary of the conditions and circumstances surrounding the fatality is intended to provide context to the agency's recommendations and is not intended to be definitive for purposes of determining any claim or benefit.

|

For further information, visit the program Web site at www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire or call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).

This page was last updated on 12/17/2010.

- Page last reviewed: November 18, 2015

- Page last updated: October 15, 2014

- Content source:

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Division of Safety Research

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir