CDC at Work: On Call 24/7 for Naegleria fowleri Infections, the Brain-eating Ameba

From CDC Connects, CDC’s Employee Intranet (12/17/2015)

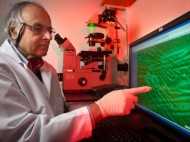

Jennifer Cope and her colleagues in the Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch know more about Naegleria fowleri, the free-living ameba that causes PAM, than anyone else in the world.

Every summer as the weather heats up, Jennifer Cope, MD, MPH, gets ready for calls from doctors and health departments across the country. They’re looking for answers about a rare and deadly disease known as PAM (primary amebic meningoencephalitis) and a drug to help treat PAM that is available through CDC and nowhere else in the United States.

Cope and her colleagues in the Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch (WDPB) of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID) know more about Naegleria fowleri, the free-living ameba that causes PAM, than anyone else in the world. And they’re on a mission to make a difference with that knowledge since they serve as frontline resources for physicians and health departments around the country.

What do a lake, a Neti pot, and a slip-n-slide have in common?

Each of these has been associated with a PAM infection in recent years. Water is, of course, what they have in common. It is normal to find Naegleria fowleri in rivers, freshwater lakes, and soil, especially in the southern United States. Naegleria fowleri thrives in warm fresh water up to 115 degrees, so most infections occur as a result of swimming. However, for the first time in the United States, infections have also been linked to use of water from municipal water systems where there is not enough chlorine to disinfect the water.

Here’s the tricky part. You can’t get PAM from ingesting water contaminated with Naegleria fowleri; you can only get it when contaminated water goes up into your nose.

Biochemical Wonder/Parent’s Nightmare

Michael Beach, has been studying Naegleria fowleri for 20 years. He describes the ameba as a “biochemical wonder” that switches readily between three distinct forms, depending on the conditions and availability of the bacteria it feeds on.

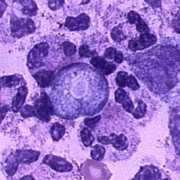

Michael Beach, PhD, chief of the Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch, has been studying Naegleria fowleri for 20 years. He describes the ameba as a “biochemical wonder” that switches readily between three distinct forms, depending on the conditions and availability of the bacteria it feeds on. The stages are so different, in fact, that scientists thought for many years they were actually seeing two different species. The creepy-crawly trophozoite stage is the dangerous one. In this stage, if Naegleria fowleri-contaminated water gets up the nose—think of diving, swimming underwater, or dunking, as kids playing in the water will do—the trophozoite can migrate along the olfactory nerve to the brain. Once in the brain, the ameba begins to destroy cells, causing meningoencephalitis (inflammation of the brain and spinal cord) and death around five days after symptoms appear. Sadly, most of Naegleria fowleri’s victims are children, probably because they are the ones splashing about in warmer shallow water and stirring up the sediment where more of the ameba are concentrated.

Now, let’s suppose you put Naegleria fowleri trophozoites into distilled water. Within 15–30 minutes, the trophozoites will convert to the flagellated form, in which it can zip around looking for food. If the Naegleria fowleri flagellate finds no food, or encounters other adverse conditions such as extreme heat or cold, it morphs into an environmentally-resistant cyst until conditions are more favorable. “The number of genes turning on and off to create this different life stage in a small amount of time makes Naegleria fowleri fascinating to CDC’s disease detectives,” says Beach.

Low Incidence High Consequence Pathogen

CDC has been studying Naegleria fowleri and three other amebae—Balamuthia, Acanthomoeba, and Sappinia—since G.S. Visvesvara, known to his colleagues as “Vish,” set up the free-living ameba laboratory in 1978.

CDC has been studying Naegleria fowleri and three other amebae—Balamuthia, Acanthomoeba, and Sappinia—since G.S. Visvesvara, PhD, known to his colleagues as “Vish,” set up the free-living ameba laboratory in 1978. Although infections from the other amebae can be life-threatening, the devastating Naegleria fowleri infections progress much more swiftly, requiring immediate action.

The United States sees just a few PAM cases each summer—CDC has seen five cases in 2015. In contrast, people make hundreds of millions of visits to lakes and rivers to swim each year. Yet when news breaks that someone has gotten the brain-eating ameba from using a neti pot to irrigate the sinuses or playing in a lake, parents may understandably panic. Unknown risks are always scary. CDC’s role in sharing information about Naegleria fowleri cannot be underestimated. “Consider what happens when there’s a PAM infection from lake water in Florida, where everyone swims,” says Beach. “There are huge social and economic issues that can be overwhelming for a local health department.”

"Without us, who’s going to have the expertise?"

Recognizing that CDC could do more than laboratory diagnoses to help doctors, health departments, and Naegleria fowleri victims, Beach and a group of epidemiology elective students set out to develop a national database on Naegleria fowleri. “We started by going through Vish’s handwritten notebooks, every piece of paper we could find, and everything we could find in the literature. We pulled it all together, archived it, and formed a workgroup with the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists to finalize the database.”

As they work systematically to fill in the blanks about Naegleria fowleri, Beach and his team also focus on the pressing question, “How can we make a difference with what we know?” The answer is a balance of:

- epidemiology to systematically fill in the blanks about Naegleria fowleri,

- communications to push the information out to clinicians and the public, and

- consultation with clinicians seeking help with diagnosis and treatment.

"If you’re not looking for it, you won’t find it."

Naegleria fowleri in its trophozoite stage

“The symptoms of PAM look exactly like other forms of meningitis,” says Cope, CDC’s first full-time free-living ameba epidemiologist, a key member of the team and the person who has the most contact with clinicians and the public. “It has to be on your differential [short list of diseases to consider], and you have to ask the right questions about exposure during the last seven to ten days.” Once a clinician has seen it, though, he or she is unlikely to forget it. Cope should know. She’s the one who takes the calls, 24/7, from physicians around the world, and CDC’s lab makes most of the diagnoses in the United States. Unfortunately, about three-quarters of PAM diagnoses, now conducted by Ibne Ali, Vish’s successor in the lab, are made after the patient has died.

If clinicians contact CDC before an infection has progressed too far, CDC can overnight an experimental drug, miltefosine, that shows promise in treating PAM. Miltefosine had already been shown to treat another parasite, leishmaniasis, when Vish tested it against Naegleria fowleri in CDC’s lab. The drug is not commercially available in the United States, but CDC has received US Food and Drug Administration approval to stock and supply miltefosine under an expanded access Investigational New Drug (IND) protocol. “Until it is easily available in the United States, we’re committed to supplying miltefosine,” says Cope. This season, she shipped out miltefosine to 14 potential patients.

"What if the thing we take for granted is not safe?"

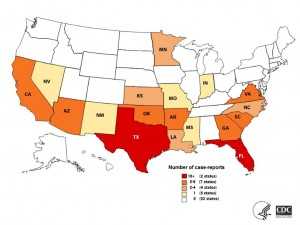

Number of case reports of PAM by state of exposure, United States, 1962–2014

Since Cope began working with the waterborne branch in 2011, the team has recorded some changes in how and where people get PAM. Most cases crop up in 16 states across the southern United States, but recent cases derived from lakes in Kansas and as far north as Minnesota may be a sign of things to come as the climate continues to warm. “It’s hard to know what to say about swimming in a lake. If you want no risk, then that means you shouldn’t swim. People have to make a judgment call. If I’m in a very shallow, warm swimming area, I can choose to close my nose or go into a deeper section where the water is cooler, and I don’t stir up the sediment,” says Beach.

Another effect of climate change are changes in the routes of spreading the disease, such as instances of Naegleria fowleri spread through public water systems. CDC and the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals confirmed Naegleria fowleri colonization in the public water systems of both St. Bernard and DeSoto Parishes in 2013; in each parish, a person died from PAM after using tap water in a neti pot for sinus irrigation. “Your water is safe to drink, but it’s not sterile so shouldn’t be used for the more sensitive parts of the body like your eyes or nose,” says Beach. “We’re chlorinating to kill amebas in the water system, but the pipes between the plant and your tap have a scum layer in them, and that’s where the amebas graze on bacteria as a food source. We want to make sure they’re not getting up your nose or onto your contact lenses.”

CDC also investigated a case of PAM in a Muslim male in St. Thomas, USVI who used tap water to irrigate his sinuses as a part of his religious practice. CDC’s team worked with imams and the Islamic Medical Association of North America to develop culturally sensitive materials about what quality of water is needed for these practices and translated them into Urdu and Arabic. With over a billion Muslims in the world, many of whom live in areas where the water is warmer, it’s important to reach them with this simple, live-saving message.

"We need to keep our eyes on the microscope continuously."

Looking to the future, Cope has promised parent advocacy groups that she will update the Naegleria fowleri website annually to keep everyone notified about all aspects of the ameba. The team is eager to share what they have learned, and they will continue to look for better ways to assess water samples and potential new treatments. “As a frontline national resource, we need to keep our eyes on the microscope continuously,” says Beach. “That’s the only way to understand what’s going on and monitor things so CDC has programs that continue to be relevant and make sense.”

- Page last reviewed: February 28, 2017

- Page last updated: February 28, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir