Assessing Haitian Patients, Immigrants, and Refugees for Rabies

Updated: May 28, 2010

Posted: March 1, 2010

Haiti Pre-decision Brief for Public Health Action (added May 28, 2010).

Background

Rabies is an acute, progressive viral encephalitis transmitted by bites from rabid mammals, and was a public health concern in Haiti even before the earthquake of January 12, 2010. From 2007-2009, Haiti had the highest number of human rabies cases transmitted via dogs in the Americas as well as persistent rabies in the mongoose population. Repercussions after the earthquake have included widespread breakdown in infrastructure and the administration of essential health services. Many Haitians remain injured, homeless and living in tent cities. Similarly, many dogs in Haiti have also been displaced, left without food and basic veterinary care. Such conditions exacerbate the rabies situation and enhance the opportunities for dog bites to occur. Given the enzootic nature of rabies in Haiti, and the increased risk for canine and other animal bites, improved awareness of rabies should be promoted when assessing Haitian patients, immigrants, and refugees. Though rabies is nearly always fatal once symptoms appear, the disease can be prevented if postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) is administered soon after an exposure occurs. Recognizing rabies virus exposures, and suspect human rabies occurrence, can prevent future cases and aid in implementation of appropriate prevention, control, and treatment measures.

Evaluating Exposures

Transmission occurs when virus is introduced into a bite wound, open cuts in the skin, or onto mucous membranes (such as the mouth or eyes). Under most circumstances, two categories of exposure – bite and nonbite – should be evaluated:

Bite

Any penetration of the skin by teeth constitutes a bite exposure. All animal bites represent a potential risk of viral transmission, but risk varies in part with the species of biting animal, the anatomic site of the bite, and the severity of the wounds.

Nonbite

Nonbite exposures from animals rarely cause rabies. However, occasional reports of transmission by the nonbite route suggest that such exposures should be evaluated for possible PEP administration. Viral contamination of open wounds, abrasions, mucous membranes, or theoretically, scratches constitutes nonbite exposures.

Other animal contacts, such as petting a rabid animal, or contact with blood, urine, or feces of a rabid animal, does not constitute an exposure and is not an indication for PEP.

Postexposure Prophylaxis

All PEP should begin with immediate gentle irrigation with clean water, or a dilute water and povidone-iodine solution, if available. For persons who have never been vaccinated previously against rabies, PEP should always include wound infiltration with human rabies immune globulin (HRIG) and the administration of multiple doses of human rabies vaccine (days 0, 3, 7, and 14). Persons who have been vaccinated previously should receive only rabies vaccine (days 0 and 3). The combination of HRIG and vaccine is recommended for both bite and nonbite exposures, regardless of the interval between exposure and initiation of PEP. Once human rabies is suspected in an encephalitic patient, PEP is not warranted.

Recognizing Rabies in Humans

After exposure, the incubation period ranges from 1 to 3 months, but may be quite variable. Early symptoms of rabies in humans are nonspecific, consisting of fever, headache, and general malaise. As the disease progresses, neurological symptoms appear in a few days, and may include insomnia, anxiety, confusion, slight or partial paralysis, excitation, hallucinations, agitation, hypersalivation, difficulty swallowing, and hydrophobia/aerophobia. Progressive worsening of neurologic signs is characteristic of rabies, and should be considered as a positive indicator for the disease. Laboratory tests to rule out common encephalitides (herpes, enteroviruses, arboviruses) should be performed, if possible. Negative results of these tests would increase the likelihood of rabies in the differential diagnosis. If a patient presents with symptoms similar to the ones described above, but the neurologic status does not change, and the illness continues for longer than three weeks, rabies is unlikely as the diagnosis. A history of a recent animal bite greatly increases the likelihood of rabies, but its absence should not preclude suspicion, because patients often fail to recognize, report, or recall a history of prior animal contact.

Positive Indicators for Rabies

- Nonspecific prodrome prior to onset of neurologic signs

- Neurologic signs consistent with encephalitis or myelitis:

- dysphagia

- hydrophobia

- paresis

- Progression of neurologic signs

- History of animal bite

- Negative test results for other etiologies of encephalitis

Negative Indicators for Rabies

- Improvement or no change in neurologic status

- Illness with ≥ 3 week duration

Rabies Diagnosis in Humans

Several tests are necessary to diagnose rabies ante-mortem (before death) in humans. No single test is sufficient. Tests are performed on samples of saliva, serum, spinal fluid, and skin biopsies of hair follicles at the nape of the neck. Saliva and skin tissue are tested by RT-PCR and genetic sequencing, and/or by virus isolation. Serum and spinal fluid are tested for antibodies to rabies virus. Skin biopsy specimens are examined for rabies virus antigen in the cutaneous nerves at the base of hair follicles. A brain biopsy for detection of viral antigens or nucleic acids may also be tested ante- or post-mortem. Detailed sample collection and CDC shipment information is available here: Ante Mortem Testing

Treatment

Palliative therapy is the standard of care for patients with rabies. However, given the 2004 survival of an unvaccinated teenager with rabies, aggressive experimental therapy, such as the Milwaukee Protocol![]() , can be considered in select cases.

, can be considered in select cases.

Selection Criteria for Milwaukee Protocol

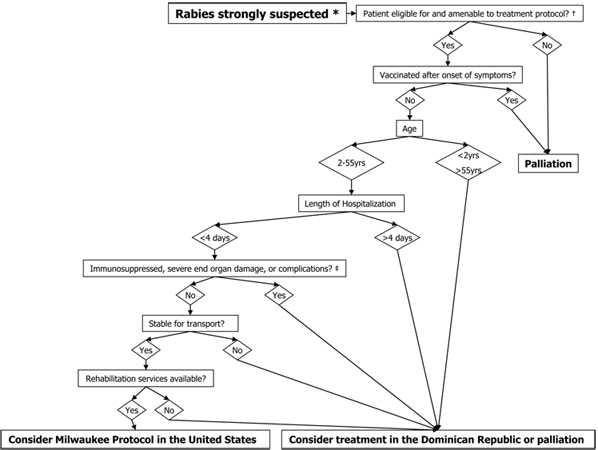

Click here for larger image.

Rabies strongly suspected *

- Patient eligible for and amenable to treatment protocol? †

- Yes: continue to “Vaccinated after onset of symptoms?”

- No: Palliation

- Vaccinated after onset of symptoms?

- Yes: Palliation

- No: continue to “Age”

- Age

- 2-55 years: continue to “Length of Hospitalization”

- < 2 years, > 55 years: Consider treatment in the Dominican Republic or palliation

- Length of hospitalization

- < 4 days: continue to “Immunosuppressed, severe end organ damage, or complications?”

- > 4 days: Consider treatment in the Dominican Republic or palliation

- Immunosuppressed, severe end organ damage, or complications?

- No: continue to “Stable for transport?”

- Yes: Consider treatment in the Dominican Republic or palliation ‡

- Stable for transport? §

- Yes: continue to “Rehabilitation services available?”

- No: Consider treatment in the Dominican Republic or palliation

- Rehabilitation services available?

- Yes: Consider Milwaukee Protocol in the United States

- No: Consider treatment in the Dominican Republic or palliation

* – Based on compatible clinical presentation including encephalitis and/or myelitis AND a history of animal exposure.

† – Patient without allergy to ketamine OR benzodiazepines OR amantadine OR BH4 OR L-arginine OR nimodipine. No contraindication or impracticality of transcranial doppler monitoring AND continuous EEG monitoring. Patient amenable to placement of an invasive device for measurement of intracranial pressure and tissue oxygen content OR brain biopsy under defined circumstances, serial lumbar punctures or phlebotomy to monitor immune response to rabies, repeat skin biopsies of nuchal skin.

‡ – HIV, HTLV-1, pregnancy, coma, cerebral edema, cardiomyopathy, pulmonary edema, renal failure, refractory hypotension, status epilepticus, CSF protein >200mg/dL

§ – Expected survival time >48 hours, normal blood pressure for age with no more than low-dose vasopressor support, AND normal ventilation and oxygenation parameters if sedated and/or intubated.

- Page last reviewed: April 22, 2011

- Page last updated: April 22, 2011

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir