Secondhand Smoke (SHS) Facts

Secondhand smoke harms children and adults, and the only way to fully protect nonsmokers is to eliminate smoking in all homes, worksites, and public places.1,2,3

You can take steps to protect yourself and your family from secondhand smoke, such as making your home and vehicles smokefree.2,3

Separating smokers from nonsmokers, opening windows, or using air filters does not prevent people from breathing secondhand smoke.1,2,3

Most exposure to secondhand smoke occurs in homes and workplaces.2,3

People are also exposed to secondhand smoke in public places—such as in restaurants, bars, and casinos—as well as in cars and other vehicles.2,3

People with lower income and lower education are less likely to be covered by smokefree laws in worksites, restaurants, and bars.4

What Is Secondhand Smoke?

- Secondhand smoke is smoke from burning tobacco products, such as cigarettes, cigars, or pipes.1,5,6

- Secondhand smoke also is smoke that has been exhaled, or breathed out, by the person smoking.5,6

- Tobacco smoke contains more than 7,000 chemicals, including hundreds that are toxic and about 70 that can cause cancer.1

Secondhand Smoke Harms Children and Adults

- There is no risk-free level of secondhand smoke exposure; even brief exposure can be harmful to health.1,2,6

- Since 1964, approximately 2,500,000 nonsmokers have died from health problems caused by exposure to secondhand smoke.1

Health Effects in Children

In children, secondhand smoke causes the following:1,2,3

- Ear infections

- More frequent and severe asthma attacks

- Respiratory symptoms (for example, coughing, sneezing, and shortness of breath)

- Respiratory infections (bronchitis and pneumonia)

- A greater risk for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)

Health Effects in Adults

In adults who have never smoked, secondhand smoke can cause:

- Heart disease

- For nonsmokers, breathing secondhand smoke has immediate harmful effects on the heart and blood vessels.1,3

- It is estimated that secondhand smoke caused nearly 34,000 heart disease deaths each year during 2005–2009 among adult nonsmokers in the United States.1

- Lung cancer1,7

- Secondhand smoke exposure caused more than 7,300 lung cancer deaths each year during 2005–2009 among adult nonsmokers in the United States.1

- Stroke1

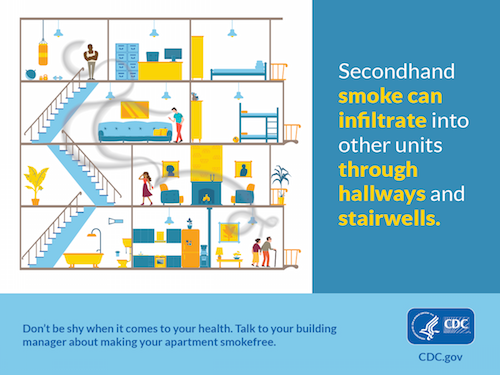

Secondhand smoke can infiltrate into other units through hallways and stairwells.

Larger infographic

Smokefree laws can reduce the risk for heart disease and lung cancer among nonsmokers.1

Patterns of Secondhand Smoke Exposure

Exposure to secondhand smoke can be measured by testing saliva, urine, or blood to see if it contains cotinine.3 Cotinine is created when the body breaks down the nicotine found in tobacco smoke.

Secondhand Smoke Exposure Has Decreased in Recent Years

- Measurements of cotinine show that exposure to secondhand smoke has steadily decreased in the United States over time.

- During 1988–1991, almost 90 of every 100 (87.9%) nonsmokers had measurable levels of cotinine.7

- During 2007–2008, about 40 of every 100 (40.1%) nonsmokers had measurable levels of cotinine.7

- During 2011–2012, about 25 of every 100 (25.3%) nonsmokers had measurable levels of cotinine.8

- The decrease in exposure to secondhand smoke is likely due to:8

- The growing number of states and communities with laws that do not allow smoking in indoor areas of workplaces and public places, including restaurants, bars, and casinos

- The growing number of households with voluntary smokefree home rules

- Significant declines in cigarette smoking rates

- The fact that smoking around nonsmokers has become much less socially acceptable

Many People in the United States Are Still Exposed to Secondhand Smoke

- During 2011–2012, about 58 million nonsmokers in the United States were exposed to secondhand smoke.8

- Among children who live in homes in which no one smokes indoors, those who live in multi-unit housing (for example, apartments or condos) have 45% higher cotinine levels (or almost half the amount) than children who live in single-family homes.9

- During 2011–2012, 2 out of every 5 children ages 3 to 11—including 7 out of every 10 Black children—in the United States were exposed to secondhand smoke regularly.8

- During 2011–2012, more than 1 in 3 (36.8%) nonsmokers who lived in rental housing were exposed to secondhand smoke.8

Differences in Secondhand Smoke Exposure

Racial and Ethnic Groups8

- Cotinine levels have declined in all racial and ethnic groups, but cotinine levels continue to be higher among non-Hispanic Black Americans than non-Hispanic White Americans and Mexican Americans. During 2011–2012:

- Nearly half (46.8%) of Black nonsmokers in the United States were exposed to secondhand smoke.

- About 22 of every 100 (21.8%) non-Hispanic White nonsmokers were exposed to secondhand smoke.

- Nearly a quarter (23.9%) of Mexican American nonsmokers were exposed to secondhand smoke.

Income8

- Secondhand smoke exposure is higher among people with low incomes.

- During 2011–2012, more than 2 out of every 5 (43.2%) nonsmokers who lived below the poverty level were exposed to secondhand smoke.

Occupation10

- Differences in secondhand smoke exposure related to people’s jobs decreased over the past 20 years, but large differences still exist.

- Some groups continue to have high levels of secondhand smoke exposure. These include:

- Blue-collar workers and service workers

- Construction workers

What You Can Do

You can protect yourself and your family from secondhand smoke by:2,3,4

- Quitting smoking if you are not already a nonsmoker

- Not allowing anyone to smoke anywhere in or near your home

- Not allowing anyone to smoke in your car, even with the windows down

- Making sure your children’s day care center and schools are tobacco-free

- Seeking out restaurants and other places that do not allow smoking (if your state still allows smoking in public areas)

- Teaching your children to stay away from secondhand smoke

- Being a good role model by not smoking or using any other type of tobacco

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014 [accessed 2017 Feb 21].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A Report of the Surgeon General: How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: What It Means to You. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2010 [accessed 2017 Feb 21].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006 [accessed 2017 Feb 21].

- Huang J, King BA, Babb SD, Xu X, Hallett C, Hopkins M. Sociodemographic Disparities in Local Smoke-Free Law Coverage in 10 States. American Journal of Public Health 2015;105(9):1806–13 [cited 2017 Feb 21].

- Institute of Medicine. Secondhand Smoke Exposure and Cardiovascular Effects: Making Sense of the Evidence. Washington: National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine, 2009 [accessed 2017 Feb 21].

- National Toxicology Program. Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition. Research Triangle Park (NC): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2016 [accessed 2017 Feb 21].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Nonsmokers’ Exposure to Secondhand Smoke—United States, 1999–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2010;59(35):1141–6 [accessed 2017 Feb 21].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Disparities in Nonsmokers’ Exposure to Secondhand Smoke—United States, 1999–2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2015;64(4):103–8 [accessed 2017 Feb 21].

- Wilson KM, Klein JD, Blumkin AK, Gottlieb M, Winickoff JP.Tobacco Smoke Exposure in Children Who Live in Multiunit Housing. [PDF–575 KB] Pediatrics 2011:127(1):85-92 [accessed 2017 Feb 21].

- Arheart KL, Lee DJ, Dietz NA, Wilkinson JD, Clark III JD, LeBlanc WG, Serdar B, Fleming LE. Declining Trends in Serum Cotinine Levels in U.S. Worker Groups: The Power of Policy. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2008;50(1):57–63 [cited 2017 Feb 21].

For Further Information

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Office on Smoking and Health

E-mail: tobaccoinfo@cdc.gov

Phone: 1-800-CDC-INFO

Media Inquiries: Contact CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health press line at 770-488-5493.

- Page last reviewed: February 21, 2017

- Page last updated: February 21, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir