Insecticide Resistance

The use of insecticides to kill mosquitoes that spread Zika, dengue, and chikungunya viruses, is one part of an integrated mosquito management program. Insecticides may be used by professionals and by homeowners. Insecticides can be applied by hand (indoor and outdoor sprays and foggers), by truck, or by aerial (airplane) spraying.

Over time and repeated use, insecticide resistance can occur in mosquito populations. Insecticide resistance is an overall reduction in the ability of an insecticide product to kill mosquitoes. This means that, when used as directed, the product no longer works, or only partially works. Insecticide resistance can be product specific, or it can develop to a certain class(es) of product.

In order to delay or prevent the development of insecticide resistance in vector populations, integrated vector management programs should include a resistance management component (Florida Coordinating Council on Mosquito Control 1998). Ideally, this should include annual monitoring of the status of resistance in target populations to:

- Provide baseline data for program planning and pesticide selection before the start of control operations.

- Detect resistance at an early stage so that timely management can be implemented.

- Continuously monitor the effect of control strategies on insecticide resistance.

How Insecticide Resistance is Measured

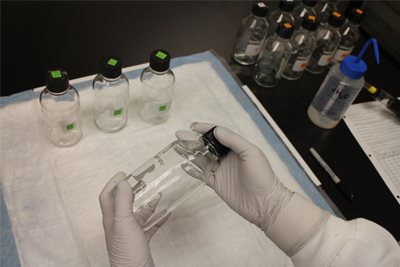

Monitoring for resistance in the vector population is essential and is useful in determining the potential causes for control failures, should they occur. CDC has developed an assay to determine if a particular insecticide active ingredient is able to kill mosquito vectors. The technique, referred to as the CDC bottle bioassay, is simple, rapid, and economical compared with alternatives. The results can help guide the choice of insecticide used for spraying.

How the Bottle Bioassay Works

- A bottle is coated with a known amount of insecticide (diagnostic dose). Mosquitoes are then put into the bottle and observed for 2 hours.

- Resistance is determined by the percentage of mosquitoes that die (mortality rate) at the pre-determined threshold time during those 2 hours. The test should be run for the entire 2 hours unless all mosquitoes have died earlier than the 2 hours.

Bottle Bioassay Threshold Times and Amounts

CDC has determined bottle bioassay threshold times and diagnostic doses for several species of mosquitoes. Using the suggested bottle diagnostic dosages, the threshold times for various susceptible colonies are provided below. The CDC entomology laboratory uses these threshold times and amounts for their bottle bioassays. The concentrations and cut-off times can be used as a starting point for determining diagnostic doses and threshold times for additional species if susceptible colonies or populations are available. Once developed, the test can be routinely used for insecticide resistance testing.

| Chemical | Final Concentration/Bottle µg/bottle | Ae. aegypti REX colony | Ae. albopictus LC colony | Cx. molestus colony | Cx. pipiens NY/Chicago colony | Cx. tarsalis BFS/KNWR colony | Cx. quinque SEABRING colony |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% Mortality Expected (minutes) | |||||||

| Chlorpyrifos | 20 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 90 | 60 | 45 |

| Deltamethrin | 0.75 | 30 | 30 | 120+ | 45 | TBD | 60 |

| Etofenprox | 12.5 | 15 | 30 | 105 | 15 | 60 | 30 |

| Fenthion | 800 | TBD | TBD | 30 | 75 | 45 | 45 |

| Malathion | 50 | 30 | 30 | ||||

| Malathion | 400 | 15 | 30 | 30 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Naled | 2.25 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Permethrin | 15 | 15 | 15 | ||||

| Permethrin | 43 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Prallethrin | 0.05 | 120+ | 120+ | 120+ | 60 | 120+ | 60 |

| Pyrethrum | 15 | 15 | 30 | 120+ | 45 | 30 | 45 |

| Resmethrin | 30 | 5 | 10 | 30 | 15 | 10 | 30 |

| Sumethrin | 20 | 10 | 45 | 120 | 30 | 30 | 45 |

Information for Aedes aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and four Culex species mosquitoes are provided for areas where these species may be co-circulating. Culex species mosquitoes are important vectors of other arboviruses such as West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, and Western equine encephalitis virus, which are endemic in the United States.

- Page last reviewed: September 6, 2017

- Page last updated: September 6, 2017

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir