Conjugated estrogens

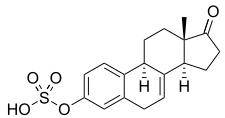

Estrone sulfate, the primary active component in conjugated estrogens (constitutes about 50 to 70% of total content). | |

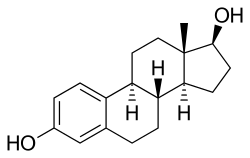

Equilin sulfate, the second most major active component in conjugated estrogens (constitutes about 20 to 30% of total content). | |

| Combination of | |

|---|---|

| Estrone sulfate | Estrogen |

| Equilin sulfate | Estrogen |

| 17α-Dihydro-equilin sulfate | Estrogen |

| Names | |

| Trade names | Cenestin, Enjuvia, Congest, C.E.S., Premarin, Prempro (with MPA), Premphase (with MPA), others |

| Other names | CEs; Conjugated equine estrogens; CEEs; Pregnant mares' urine; Premarin; Estrogens, conjugated |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Estrogen |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, topical, vaginal, intravenous injection, intramuscular injection[1][2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| US NLM | Conjugated estrogens |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | Variable[3] |

| Protein binding | High (to albumin and SHBG)[3][1] |

| Metabolism | Liver[3][1] |

| Elimination half-life | Estrone: 26.7 hours Estrone (BA): 14.8 hours Equilin: 11.4 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Urine[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| PubChem SID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ATC code | |

Conjugated estrogens (CEs), or conjugated equine estrogens (CEEs), sold under the brand name Premarin among others, is an estrogen medication which is used in menopausal hormone therapy and for various other indications.[5][3][1][6] It is a mixture of the sodium salts of estrogen conjugates found in horses, such as estrone sulfate and equilin sulfate.[1][6][5] CEEs are available in the form of both natural preparations manufactured from the urine of pregnant mares and fully synthetic replications of the natural preparations.[7][8] They are formulated both alone and in combination with progestins such as medroxyprogesterone acetate.[5] CEEs are usually taken by mouth, but can also be given by application to the skin or vagina as a cream or by injection into a blood vessel or muscle.[1][2]

Side effects of CEEs include breast tenderness and enlargement, headache, fluid retention, and nausea among others.[3][1] It may increase the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer in women with an intact uterus if it is not taken together with a progestogen like progesterone.[3][1] The medication may also increase the risk of blood clots, cardiovascular disease, and, when combined with most progestogens, breast cancer.[9] CEEs are estrogens, or agonists of the estrogen receptor, the biological target of estrogens like estradiol.[1][3] Compared to estradiol, certain estrogens in CEEs are more resistant to metabolism, and the medication shows relatively increased effects in certain parts of the body like the liver.[1] This results in an increased risk of blood clots and cardiovascular disease with CEEs relative to estradiol.[1][10]

Premarin, the major brand of CEEs in use, is manufactured by Wyeth and was first marketed in 1941 in Canada and in 1942 in the United States.[6] It is the most commonly used form of estrogen in menopausal hormone therapy in the United States.[11][12] However, it has begun to fall out of favor relative to bioidentical estradiol, which is the most widely used form of estrogen in Europe for menopausal hormone therapy.[12][13][14][15] CEEs are available widely throughout the world.[5] An estrogen preparation very similar to CEEs but differing in source and composition is esterified estrogens.[1] In 2017, it was the 206th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[16][17]

Medical uses

CEEs are a form of hormone therapy used in women.[18] It is used most commonly in postmenopausal women who have had a hysterectomy to treat hot flashes, and burning, itching, and dryness of the vagina and surrounding areas.[19] It must be used in combination with a progestogen in women who have not had a hysterectomy.[1] For women already taking the medication, it can be used to treat osteoporosis, although it is not recommended solely for this use.[20] Some lesser known uses are as a means of high-dose estrogen therapy in the treatment of breast cancer in both women and men and in the treatment of prostate cancer in men.[21][22] It has been used at a dosage of 2.5 mg three times per day (7.5 mg/day total) for prostate cancer.[23][24]

CEEs are specifically approved in countries such as the United States and Canada for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes) and vulvovaginal atrophy (atrophic vaginitis, atrophic urethritis) associated with menopause, hypoestrogenism due to hypogonadism, ovariectomy, or primary ovarian failure, abnormal uterine bleeding, the palliative treatment of metastatic breast cancer in women, the palliative treatment of advanced androgen-dependent prostate cancer in men, and the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis.[4][25][5] The intravenous formulation of CEEs is specifically used to rapidly limit bleeding in women with hemorrhage due to dysfunctional uterine bleeding.[2][26]: 318 [27]: 60

| Route/form | Estrogen | Low | Standard | High | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Estradiol | 0.5–1 mg/day | 1–2 mg/day | 2–4 mg/day | |||

| Estradiol valerate | 0.5–1 mg/day | 1–2 mg/day | 2–4 mg/day | ||||

| Estradiol acetate | 0.45–0.9 mg/day | 0.9–1.8 mg/day | 1.8–3.6 mg/day | ||||

| Conjugated estrogens | 0.3–0.45 mg/day | 0.625 mg/day | 0.9–1.25 mg/day | ||||

| Esterified estrogens | 0.3–0.45 mg/day | 0.625 mg/day | 0.9–1.25 mg/day | ||||

| Estropipate | 0.75 mg/day | 1.5 mg/day | 3 mg/day | ||||

| Estriol | 1–2 mg/day | 2–4 mg/day | 4–8 mg/day | ||||

| Ethinylestradiola | 2.5 μg/day | 5–15 μg/day | – | ||||

| Nasal spray | Estradiol | 150 μg/day | 300 μg/day | 600 μg/day | |||

| Transdermal patch | Estradiol | 25 μg/dayb | 50 μg/dayb | 100 μg/dayb | |||

| Transdermal gel | Estradiol | 0.5 mg/day | 1–1.5 mg/day | 2–3 mg/day | |||

| Vaginal | Estradiol | 25 μg/day | – | – | |||

| Estriol | 30 μg/day | 0.5 mg 2x/week | 0.5 mg/day | ||||

| IM or SC injection | Estradiol valerate | – | – | 4 mg 1x/4 weeks | |||

| Estradiol cypionate | 1 mg 1x/3–4 weeks | 3 mg 1x/3–4 weeks | 5 mg 1x/3–4 weeks | ||||

| Estradiol benzoate | 0.5 mg 1x/week | 1 mg 1x/week | 1.5 mg 1x/week | ||||

| SC implant | Estradiol | 25 mg 1x/6 months | 50 mg 1x/6 months | 100 mg 1x/6 months | |||

| Footnotes: a = No longer used or recommended, due to health concerns. b = As a single patch applied once or twice per week (worn for 3–4 days or 7 days), depending on the formulation. Note: Dosages are not necessarily equivalent. Sources: See template. | |||||||

Available forms

Natural CEEs, as Premarin, are available in the form of oral tablets (0.3 mg, 0.625 mg, 0.9 mg, 1.25 mg, or 2.5 mg), creams for topical or vaginal administration (0.625 mg/g), and vials for intravenous or intramuscular injection (25 mg/vial).[2][28] Synthetic CEEs, such as Cenestin (Synthetic A), Enjuvia (Synthetic B), and generic formulations, are available in the form of oral tablets (0.3 mg, 0.45 mg, 0.625 mg, 0.9 mg, or 1.25 mg) and creams for topical or vaginal administration (0.625 mg/g).[2][29]

Contraindications

Contraindications of CEEs include breast cancer and a history of venous thromboembolism, among others.

Side effects

The most common side effects associated with CEEs are vaginal yeast infections, vaginal spotting or bleeding, painful menses, and cramping of the legs. While there are some contradictory data, estrogen alone does not appear to increase the risk of coronary heart disease or breast cancer, unlike the case of estrogen in combination with certain progestins such as levonorgestrel or medroxyprogesterone acetate.[30] Only a few clinical studies have assessed differences between oral CEEs and oral estradiol in terms of health parameters.[31] Oral CEEs have been found to possess a significantly greater risk of thromboembolic and cardiovascular complications than oral estradiol (OR = 2.08) and oral esterified estrogens (OR = 1.78).[31][32][33] However, in another study, the increase in venous thromboembolism risk with oral CEEs plus medroxyprogesterone acetate and oral estradiol plus norethisterone acetate was found to be equivalent (RR = 4.0 and 3.9, respectively).[34][35] As of present, there are no randomized controlled trials that would allow for unambiguous conclusions.[31]

| Clinical outcome | Hypothesized effect on risk |

Estrogen and progestogen (CEs 0.625 mg/day p.o. + MPA 2.5 mg/day p.o.) (n = 16,608, with uterus, 5.2–5.6 years follow up) |

Estrogen alone (CEs 0.625 mg/day p.o.) (n = 10,739, no uterus, 6.8–7.1 years follow up) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | AR | HR | 95% CI | AR | ||

| Coronary heart disease | Decreased | 1.24 | 1.00–1.54 | +6 / 10,000 PYs | 0.95 | 0.79–1.15 | −3 / 10,000 PYs |

| Stroke | Decreased | 1.31 | 1.02–1.68 | +8 / 10,000 PYs | 1.37 | 1.09–1.73 | +12 / 10,000 PYs |

| Pulmonary embolism | Increased | 2.13 | 1.45–3.11 | +10 / 10,000 PYs | 1.37 | 0.90–2.07 | +4 / 10,000 PYs |

| Venous thromboembolism | Increased | 2.06 | 1.57–2.70 | +18 / 10,000 PYs | 1.32 | 0.99–1.75 | +8 / 10,000 PYs |

| Breast cancer | Increased | 1.24 | 1.02–1.50 | +8 / 10,000 PYs | 0.80 | 0.62–1.04 | −6 / 10,000 PYs |

| Colorectal cancer | Decreased | 0.56 | 0.38–0.81 | −7 / 10,000 PYs | 1.08 | 0.75–1.55 | +1 / 10,000 PYs |

| Endometrial cancer | – | 0.81 | 0.48–1.36 | −1 / 10,000 PYs | – | – | – |

| Hip fractures | Decreased | 0.67 | 0.47–0.96 | −5 / 10,000 PYs | 0.65 | 0.45–0.94 | −7 / 10,000 PYs |

| Total fractures | Decreased | 0.76 | 0.69–0.83 | −47 / 10,000 PYs | 0.71 | 0.64–0.80 | −53 / 10,000 PYs |

| Total mortality | Decreased | 0.98 | 0.82–1.18 | −1 / 10,000 PYs | 1.04 | 0.91–1.12 | +3 / 10,000 PYs |

| Global index | – | 1.15 | 1.03–1.28 | +19 / 10,000 PYs | 1.01 | 1.09–1.12 | +2 / 10,000 PYs |

| Diabetes | – | 0.79 | 0.67–0.93 | 0.88 | 0.77–1.01 | ||

| Gallbladder disease | Increased | 1.59 | 1.28–1.97 | 1.67 | 1.35–2.06 | ||

| Stress incontinence | – | 1.87 | 1.61–2.18 | 2.15 | 1.77–2.82 | ||

| Urge incontinence | – | 1.15 | 0.99–1.34 | 1.32 | 1.10–1.58 | ||

| Peripheral artery disease | – | 0.89 | 0.63–1.25 | 1.32 | 0.99–1.77 | ||

| Probable dementia | Decreased | 2.05 | 1.21–3.48 | 1.49 | 0.83–2.66 | ||

| Abbreviations: CEs = conjugated estrogens. MPA = medroxyprogesterone acetate. p.o. = per oral. HR = hazard ratio. AR = attributable risk. PYs = person–years. CI = confidence interval. Notes: Sample sizes (n) include placebo recipients, which were about half of patients. "Global index" is defined for each woman as the time to earliest diagnosis for coronary heart disease, stroke, pulmonary embolism, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer (estrogen plus progestogen group only), hip fractures, and death from other causes. Sources: See template. | |||||||

| Type | Route | Medications | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menopausal hormone therapy | Oral | Estradiol alone ≤1 mg/day >1 mg/day | 1.27 (1.16–1.39)* 1.22 (1.09–1.37)* 1.35 (1.18–1.55)* |

| Conjugated estrogens alone ≤0.625 mg/day >0.625 mg/day | 1.49 (1.39–1.60)* 1.40 (1.28–1.53)* 1.71 (1.51–1.93)* | ||

| Estradiol/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 1.44 (1.09–1.89)* | ||

| Estradiol/dydrogesterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 | 1.18 (0.98–1.42) 1.12 (0.90–1.40) 1.34 (0.94–1.90) | ||

| Estradiol/norethisterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 | 1.68 (1.57–1.80)* 1.38 (1.23–1.56)* 1.84 (1.69–2.00)* | ||

| Estradiol/norgestrel or estradiol/drospirenone | 1.42 (1.00–2.03) | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 2.10 (1.92–2.31)* | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/norgestrel ≤0.625 mg/day CEEs >0.625 mg/day CEEs | 1.73 (1.57–1.91)* 1.53 (1.36–1.72)* 2.38 (1.99–2.85)* | ||

| Tibolone alone | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | ||

| Raloxifene alone | 1.49 (1.24–1.79)* | ||

| Transdermal | Estradiol alone ≤50 μg/day >50 μg/day | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) 0.94 (0.85–1.03) 1.05 (0.88–1.24) | |

| Estradiol/progestogen | 0.88 (0.73–1.01) | ||

| Vaginal | Estradiol alone | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | |

| Conjugated estrogens alone | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | ||

| Combined birth control | Oral | Ethinylestradiol/norethisterone | 2.56 (2.15–3.06)* |

| Ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel | 2.38 (2.18–2.59)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/norgestimate | 2.53 (2.17–2.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/desogestrel | 4.28 (3.66–5.01)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/gestodene | 3.64 (3.00–4.43)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/drospirenone | 4.12 (3.43–4.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/cyproterone acetate | 4.27 (3.57–5.11)* | ||

| Notes: (1) Nested case–control studies (2015, 2019) based on data from the QResearch and Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) databases. (2) Bioidentical progesterone was not included, but is known to be associated with no additional risk relative to estrogen alone. Footnotes: * = Statistically significant (p < 0.01). Sources: See template. | |||

Overdose

Estrogens, including CEEs, are relatively safe in acute overdose.

Interactions

Inhibitors and inducers of cytochrome P450 enzymes may interact with CEEs.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

CEEs are a combination of estrogens, or agonists of the estrogen receptors.[1] The major estrogen in CEEs, sodium estrone sulfate, itself is inactive, and rather serves as a prodrug of estrone and then of estradiol.[1][36][37] The transformation of estrone sulfate to estrone is catalyzed by steroid sulfatase, and of estrone into estradiol by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.[1][38] CEEs (as Premarin) and estrone have been found to be equivalent in potency in an animal model of estrogenic activity.[6] On the other hand, the active forms of the equine estrogens in CEEs, such as equilin and 17β-dihydroequilin, have greater potency in the liver relative to bioidentical estradiol, similarly to synthetic estrogens like ethinylestradiol and diethylstilbestrol.[1] This results in disproportionate effects on liver protein production compared to estradiol, although to a lesser extent than ethinylestradiol and diethylstilbestrol.[1] In addition, 17β-dihydroequilenin has shown a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM)-like profile of estrogenic activity in studies with monkeys, in which beneficial effects on bone and the cardiovascular system were observed but proliferative responses in breast or endometrium were not seen, although the clinical significance of this is unknown.[39]

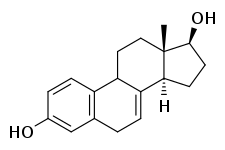

CEEs consists of the sodium salts of the sulfate esters of equine estrogens in a specific and consistent composition (see the table).[1][6] The major estrogens in CEEs are sodium estrone sulfate and sodium equilin sulfate, which together account for approximately 71.5 to 92.0% of the total content of CEEs.[5][1][6] CEEs are prodrugs of the active forms of the estrogens.[1][6][5] Sodium estrone sulfate is a prodrug of estrone, which in turn is a prodrug of estradiol, while sodium equilin sulfate is a prodrug of equilin and then of 17β-dihydroequilin.[1] As such, the major active estrogens with CEEs are estradiol and 17β-dihydroequilin, which have potent estrogenic activity and account for most of the effects of CEEs.[1] The 17α-estrogens in CEEs such as 17α-estradiol and 17α-dihydroequilin have low estrogenicity and are thought to contribute minimally to its effects.[1] There are many different steroids in natural CEE products like Premarin, as many as 230 compounds and including even androgens and progestogens, but only the estrogens are present in sufficient amounts to produce clinically-relevant effects.[6][40][11]

A dosage of 0.625 mg/day oral CEEs has been found to increase SHBG levels by 100%.[40][41] For comparison, 1 mg/day oral estradiol increased SHBG levels by 45%, while 50 µg/day transdermal estradiol increased SHBG levels by 12%.[40][41] Ethinylestradiol is more potent in its effects on liver protein synthesis than either CEEs or estradiol, with 10 µg/day oral ethinylestradiol having been found to be approximately equivalent to 1.25 mg/day CEEs.[40]

| Compound | Synonym | Proportion (%) | Relative potency in the vagina (%) | Relative potency in the uterus (%) | RBA for ERα (%) | RBA for ERβ (%) | ERα / ERβ RBA ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conjugated estrogens | – | 100 | 38 | 100 | – | – | – |

| Estrone | – | 49.1–61.5 | 30 | 32 | 26 | 52 | 0.50 |

| Equilin | Δ7-Estrone | 22.4–30.5 | 42 | 80 | 13 | 49 | 0.26 |

| 17α-Dihydroequilin | Δ7-17α-Estradiol | 13.5–19.5 | 0.06 | 2.6 | 41 | 32 | 1.30 |

| 17α-Estradiol | – | 2.5–9.5 | 0.11 | 3.5 | 19 | 42 | 0.45 |

| Δ8-Estrone | – | 3.5–3.9 | ? | ? | 19 | 32 | 0.60 |

| Equilenin | Δ6,8-Estrone | 2.2–2.8 | 1.3 | 11.4 | 15 | 20–29 | 0.50–0.75 |

| 17β-Dihydroequilin | Δ7-17β-Estradiol | 0.5–4.0 | 83 | 200 | 113 | 108 | 1.05 |

| 17α-Dihydroequilenin | Δ6,8-17α-Estradiol | 1.2–1.6 | 0.018 | 1.3 | 20 | 49 | 0.40 |

| 17β-Estradiol | – | 0.56–0.9 | 100 | ? | 100 | 100 | 1.00 |

| 17β-Dihydroequilenin | Δ6,8-17β-Estradiol | 0.5–0.7 | 0.21 | 9.4 | 68 | 90 | 0.75 |

| Δ8-17β-Estradiol | – | Small amounts | ? | ? | 68 | 72 | 0.94 |

| Notes: All listed compounds are present in conjugated estrogen products specifically in the form of the sodium salts of the sulfate esters (i.e., as sodium estrone sulfate, sodium equilin sulfate, etc.). Sources: See template. | |||||||

| Compound | Dosage for specific uses (mg usually)[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETD[lower-alpha 2] | EPD[lower-alpha 2] | MSD[lower-alpha 2] | MSD[lower-alpha 3] | OID[lower-alpha 3] | TSD[lower-alpha 3] | ||

| Estradiol (non-micron.) | 30 | ≥120–300 | 120 | 6 | - | - | |

| Estradiol (micronized) | 6–12 | 60–80 | 14–42 | 1–2 | >5 | >8 | |

| Estradiol valerate | 6–12 | 60–80 | 14–42 | 1–2 | - | >8 | |

| Estradiol benzoate | - | 60–140 | - | - | - | - | |

| Estriol | ≥20 | 120–150[lower-alpha 4] | 28–126 | 1–6 | >5 | - | |

| Estriol succinate | - | 140–150[lower-alpha 4] | 28–126 | 2–6 | - | - | |

| Estrone sulfate | 12 | 60 | 42 | 2 | - | - | |

| Conjugated estrogens | 5–12 | 60–80 | 8.4–25 | 0.625–1.25 | >3.75 | 7.5 | |

| Ethinylestradiol | 200 μg | 1–2 | 280 μg | 20–40 μg | 100 μg | 100 μg | |

| Mestranol | 300 μg | 1.5–3.0 | 300–600 μg | 25–30 μg | >80 μg | - | |

| Quinestrol | 300 μg | 2–4 | 500 μg | 25–50 μg | - | - | |

| Methylestradiol | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | |

| Diethylstilbestrol | 2.5 | 20–30 | 11 | 0.5–2.0 | >5 | 3 | |

| DES dipropionate | - | 15–30 | - | - | - | - | |

| Dienestrol | 5 | 30–40 | 42 | 0.5–4.0 | - | - | |

| Dienestrol diacetate | 3–5 | 30–60 | - | - | - | - | |

| Hexestrol | - | 70–110 | - | - | - | - | |

| Chlorotrianisene | - | >100 | - | - | >48 | - | |

| Methallenestril | - | 400 | - | - | - | - | |

| Estrogen | HF | VE | UCa | FSH | LH | HDL-C | SHBG | CBG | AGT | Liver |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Estrone | ? | ? | ? | 0.3 | 0.3 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Estriol | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | ? | ? | ? | 0.67 |

| Estrone sulfate | ? | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8–0.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5–0.7 | 1.4–1.5 | 0.56–1.7 |

| Conjugated estrogens | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.1–1.3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.0–3.2 | 1.3–1.5 | 5.0 | 1.3–4.5 |

| Equilin sulfate | ? | ? | 1.0 | ? | ? | 6.0 | 7.5 | 6.0 | 7.5 | ? |

| Ethinylestradiol | 120 | 150 | 400 | 60–150 | 100 | 400 | 500–600 | 500–600 | 350 | 2.9–5.0 |

| Diethylstilbestrol | ? | ? | ? | 2.9–3.4 | ? | ? | 26–28 | 25–37 | 20 | 5.7–7.5 |

Sources and footnotes

Notes: Values are ratios, with estradiol as standard (i.e., 1.0). Abbreviations: HF = Clinical relief of hot flashes. VE = Increased proliferation of vaginal epithelium. UCa = Decrease in UCa. FSH = Suppression of FSH levels. LH = Suppression of LH levels. HDL-C, SHBG, CBG, and AGT = Increase in the serum levels of these liver proteins. Liver = Ratio of liver estrogenic effects to general/systemic estrogenic effects (hot flashes/gonadotropins). Sources: See template. | ||||||||||

Antigonadotropic effects

A preliminary study of ovulation inhibition in women found that oral CEEs was 33% effective at 1.25 mg/day and 94% at 3.75 mg/day.[62][63] A dosage of oral CEEs of 2.5 mg three times daily (7.5 mg/day total) has been found to suppress total testosterone levels in men to an equivalent extent as 3 mg/day oral diethylstilbestrol, which is the minimum dosage of diethylstilbestrol required to consistently suppress total testosterone levels into the castrate range (<50 ng/dL).[64]

Pharmacokinetics

CEEs are hydrolyzed in the intestines during first-pass metabolism upon oral administration.[65][5] Following their absorption, they are resulfated mainly in the liver also during the first pass.[65] Following this, they serve as a circulating reservoir and are slowly rehydrolyzed into their unconjugated active forms.[65]

Oral CEEs, at a daily dosage of 0.625 mg, achieve estrone and estradiol levels of 150 pg/mL and 30–50 pg/mL, respectively, while a daily oral dosage of 1.25 mg achieves levels of 120–200 pg/mL and 40–60 pg/mL of estrone and estradiol, respectively.[66] The oral ingestion of 10 mg CEEs, which contains about 4.5 mg sodium estrone sulfate and 2.5 mg sodium equilin sulfate, produces maximal plasma concentrations of estrone and equilin of 1,400 pg/mL and 560 pg/mL within 3 and 5 hours, respectively.[66] By 24 hours post-dose of 10 mg, the levels of estrone and equilin fall to 280 pg/mL and 125 pg/mL, respectively.[66] Oral CEEs 1.25 mg/daily and oral micronized estradiol 1 mg/daily result in similar plasma concentrations of estrone and estradiol (150–300 pg/mL and 30–50 pg/mL for micronized estradiol, respectively) (oral estradiol is extensively metabolized into estrone during liver first-pass metabolism),[66] although this does not account for equilin and other equine estrogens involved in the effects of CEEs, which may be significantly more potent in comparison to estrone.[67][68] The pharmacokinetics of vaginal CEEs[69] and of intravenous CEEs have been studied as well.[70]

Extremely high concentrations of equilin are produced by typical clinical dosages of CEEs.[71] With a dosage of 1.25 mg oral CEEs, equilin levels of 1,082 to 2,465 pg/mL have been observed.[71] The clinical significance of these levels of equilin is unknown.[71]

The active forms are metabolized primarily in the liver.[5] There is some enterohepatic recirculation of CEEs.[5] Following a single oral dose of 0.625 CEEs, the biological half-life of estrone was 26.7 hours, of baseline-adjusted estrone was 14.8 hours, and of equilin was 11.4 hours.[4]

| Route | Dose | Time | E2 (↑Δ) | E1 (↑Δ) | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | 0.3 mg 0.625 mg 1.25 mg 1.25 mg 2.5 mg | 6 hours 6 hours 6 hours 1 hour 6 hours | +20 pg/mL +50 pg/mL +70 pg/mL +35–58 pg/mL +160 pg/mL | ND ND ND 110 pg/mL ND | ND ND ND 0.32–0.52 ND | |

| Vaginal (cream) | 0.3 mg 0.625 mg 0.625 mg 1.25 mg 1.25 mg 2.5 mg | ND ND ND 2 hours ND ND | +4 pg/mL +13–29 pg/mL +17 pg/mL +25 pg/mL +27 pg/mL +32 pg/mL | +20 pg/mL +29–55 pg/mL +45 pg/mL +50 pg/mL +110 pg/mL +40 pg/mL | 0.2 0.24–1.0 0.38 0.5 0.25 0.8 | |

| Intravenousa | 20 mg | 5 min 30 min 60 min 120 min | 800 pg/mL 3000 pg/mL 3500 pg/mL 3100 pg/mL | 4500 pg/mL 24000 pg/mL 19000 pg/mL 10500 pg/mL | 1:5.3 1:8.1 1:5.5 1:3.4 | |

| Notes: a = Absolute levels, not change. Sources: See template. | ||||||

| Compound | RBA to SHBG (%) | Bound to SHBG (%) | Bound to albumin (%) | Total bound (%) | MCR (L/day/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17β-Estradiol | 50 | 37 | 61 | 98 | 580 |

| Estrone | 12 | 16 | 80 | 96 | 1050 |

| Estriol | 0.3 | 1 | 91 | 92 | 1110 |

| Estrone sulfate | 0 | 0 | 99 | 99 | 80 |

| 17β-Dihydroequilin | 30 | ? | ? | ? | 1250 |

| Equilin | 8 | 26 | 13 | ? | 2640 |

| 17β-Dihydroequilin sulfate | 0 | ? | ? | ? | 375 |

| Equilin sulfate | 0 | ? | ? | ? | 175 |

| Δ8-Estrone | ? | ? | ? | ? | 1710 |

| Notes: RBA for SHBG (%) is compared to 100% for testosterone. Sources: See template. | |||||

Chemistry

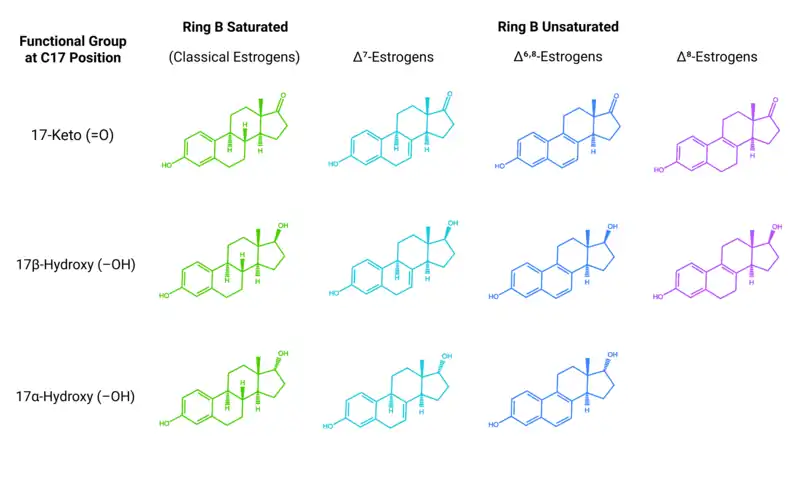

CEEs are naturally occurring estrane steroids.[1][6] They are in conjugate form, as the sodium salts of the C17β sulfate esters.[1][6] The estrogens in CEEs, in their unconjugated active forms, include bioidentical human estrogens like estradiol and estrone as well as equine-specific estrogens such as equilin and 17β-dihydroequilin.[1][6] The equine estrogens differ from human estrogens in that they have additional double bonds in the B ring of the steroid nucleus.[1][6] CEEs contain both 17β-estrogens like estradiol and 17β-dihydroequilin and the C17α epimers like 17α-estradiol and 17α-dihydroequilin.[1][6]

History

Conjugated estriol, an extract of the urine of pregnant women and sold under the brand names Progynon and Emmenin in the 1930s, was the predecessor of Premarin.[73] Both of these products contained conjugated estrogens similarly to Premarin, but the estrogens were human estrogens as opposed to equine estrogens and the composition differed. The major active ingredient in Progynon and Emmenin was estriol glucuronide.

Estrone sulfate was first isolated from the urine of pregnant mares in the late 1930s by researchers in the Department of Biochemistry at University of Toronto.[74] Premarin was first introduced in 1941 by Wyeth Ayerst as a treatment for hot flashes and other symptoms of menopause; at that time, Wyeth Ayerst only had to prove its safety, and not its efficacy.[75] In response to the 1962 Kefauver Harris Amendment the FDA had its efficacy reviewed, and in 1972 found it effective for menopausal symptoms and probably effective for osteoporosis.[76] The review also determined that two estrogens – estrone sulfate and equilin sulfate – were primarily responsible for the activity of Premarin, and it laid the groundwork for Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) submissions of generic versions.[75] In 1984 an NIH consensus panel found that estrogens were effective for preventing osteoporosis[77] and 1986 the FDA announced in the Federal Register that Premarin was effective for preventing osteoporosis.[78] This announcement led to a rapid growth in sales, and interest from generic manufacturers to introduce generic versions.[75]

Conjugated estrogens was introduced for medical use under the brand name Premarin in Canada in 1941, in the United States in 1942, and in the United Kingdom in 1956.[79]

Society and culture

Cost

In 2017, it was the 206th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[16][17]

.svg.png.webp) EstrogensConjugated costs (US)

EstrogensConjugated costs (US).svg.png.webp) EstrogensConjugated prescriptions (US)

EstrogensConjugated prescriptions (US)

Names

Estrogens, conjugated is the generic name of the drug and its USP and JAN.[80] It is also known as conjugated estrogens or as conjugated equine estrogens.[4] The brand name Premarin is a contraction of "pregnant mares' urine".

CEEs are marketed under a large number of brand names throughout the world.[5] The major brand name of the natural form of CEEs manufactured from the urine of pregnant mares is Premarin.[5] Major brand names of fully synthetic versions of CEEs include Cenestin and Enjuvia in the United States and C.E.S. and Congest in Canada.[5][7][8] CEEs are also formulated in combination with progestins.[5] Major brand names of CEEs in combination with medroxyprogesterone acetate include Prempro and Premphase in the United States, Premplus in Canada, Premique in the United Kingdom and Ireland, Premia in Australia and New Zealand, and Premelle in South Africa.[5][81] Prempak-C is a combination of CEEs and norgestrel which is used in the United Kingdom and Ireland, and Prempak N is a combination of CEEs and medrogestone which is used in South Africa.[5] Many of the aforementioned brand names are also used in other, non-English-speaking countries.[5]

Availability

CEEs are marketed and available widely throughout the world.[5][25] This includes in all English-speaking countries, throughout Europe, Latin America, Asia, and elsewhere in the world.[5][25]

Usage

Besides ethinylestradiol used in birth control pills, CEEs were the second most used estrogen in the U.S. in 2016, with 4.2 million total prescriptions filled.[16] The first most used estrogen was estradiol, with 13.4 million total prescriptions filled.[16] CEEs were the 206th most commonly prescribed medication in the U.S. that year.[16]

Health effects

Research starting in 1975 showed substantially increased risk of endometrial cancer.[82][83] Since 1976 the drug has carried a label warning about the risk.[84] As part of the Women's Health Initiative sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, a large-scale clinical trial of menopausal HRT showed that long-term use of estrogen and a progestin may increase the risk of strokes, heart attacks, blood clots, and breast cancer.[85] Following these results, Wyeth experienced a significant decline in its sales of Premarin, Prempro (CEEs and medroxyprogesterone acetate), and related products, from over $2 billion in 2002 to just over $1 billion in 2006.[86]

Litigation

This drug has been the subject of litigation; more than 13,000 people have sued Wyeth between 2002 and 2009. Wyeth and Pharmacia & Upjohn prevailed in the vast majority of hormone therapy cases previously set for trial through a combination of rulings by judges, verdicts by juries, and dismissals by plaintiffs themselves.[87] Of the company's losses, two of the jury verdicts were reversed post-trial and others are being challenged on appeal. Wyeth also won five summary judgments on Prempro cases and had 15 cases voluntarily dismissed by plaintiffs. The company won dismissals in another 3,000 cases.[88] In 2006, Mary Daniel, in a trial in Philadelphia, was awarded $1.5 million in compensatory damages as well as undisclosed punitive damages. As of 2010, Wyeth had won the last four of five cases, most recently in Virginia, finding that they were not responsible for the breast cancer of plaintiff Georgia Torkie-Tork.[89] Wyeth has been quoted as saying "many risk factors associated with breast cancer have been identified, but science cannot establish what role any particular risk factor or combination play in any individual woman's breast cancer." [90] Wyeth's counsel in the case also noted that in the WHI trial, 99.62% of women took the drug and "did not get breast cancer."[88]

Animal welfare

Animal welfare groups claim that animal husbandry and urine collection methods used in the production of CEEs cause undue stress and suffering to the mares involved. Animal activists have made claims of abuses ranging from inadequate stall size, long periods of confinement, cumbersome urine collection, and continuous breeding cycles. After reaching advanced age, many of the mares are adopted for recreation use, while some are sent to feed lots for slaughter. Despite the controversy, the USDA called the CEEs HRT industry a model of self-regulation.[91]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. S2CID 24616324. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "PREMARIN- estrogens, conjugated tablet, film coated Wyeth Pharmaceuticals LLC, a subsidiary of Pfizer Inc". labeling.pfizer.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "Conjugated estrogens". Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 2087. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Marc A. Fritz; Leon Speroff (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 751–3. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- 1 2 Kathy Moscou; Karen Snipe (1 December 2012). Pharmacology for Pharmacy Technicians Pageburst E-Book on VitalSource2: Pharmacology for Pharmacy Technicians Pageburst E-Book on VitalSource. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 573–. ISBN 978-0-323-08578-6.

- 1 2 IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; World Health Organization; International Agency for Research on Cancer (2007). Combined Estrogen-progestogen Contraceptives and Combined Estrogen-progestogen Menopausal Therapy. World Health Organization. pp. 378–. ISBN 978-92-832-1291-1. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Pickar JH, Archer DF, Kagan R, Pinkerton JV, Taylor HS (August 2017). "Safety and benefit considerations for menopausal hormone therapy". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 16 (8): 941–954. doi:10.1080/14740338.2017.1343298. PMID 28664754. S2CID 24155838.

- ↑ Scarabin PY (December 2014). "Hormones and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women". Climacteric. 17 Suppl 2: 34–7. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.956717. PMID 25223916. S2CID 5084606.

- 1 2 3 Bhavnani BR, Stanczyk FZ (July 2014). "Pharmacology of conjugated equine estrogens: efficacy, safety and mechanism of action". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 142: 16–29. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.10.011. PMID 24176763.

- 1 2 Quereda, Francisco (2017). "Hormone Therapy (I): Estrogens, Progestogens, and Androgens". Menopause. pp. 181–196. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-59318-0_11. ISBN 978-3-319-59317-3.

- ↑ L'Hermite M (August 2017). "Bioidentical menopausal hormone therapy: registered hormones (non-oral estradiol ± progesterone) are optimal". Climacteric. 20 (4): 331–338. doi:10.1080/13697137.2017.1291607. PMID 28301216. S2CID 4771048.

- ↑ Simon JA (July 2014). "What if the Women's Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead?". Menopause. 21 (7): 769–83. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000169. PMID 24398406. S2CID 30292136.

- ↑ Holtorf K (January 2009). "The bioidentical hormone debate: are bioidentical hormones (estradiol, estriol, and progesterone) safer or more efficacious than commonly used synthetic versions in hormone replacement therapy?". Postgrad Med. 121 (1): 73–85. doi:10.3810/pgm.2009.01.1949. PMID 19179815. S2CID 2060730.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Estrogens, Conjugated - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Greer, Iain A.; Ginsberg, Jeff; Forbes, Charles (29 December 2006). Women's vascular health. CRC Press. ISBN 9780340809976. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Nezhat, Camran; Nezhat, Farr; Nezhat, Ceana (7 July 2008). Nezhat's Operative gynecologic laparoscopy and hysteroscopy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139472005. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ Maeda, Sergio Setsuo; Lazaretti-Castro, Marise; Maeda, Sergio Setsuo; Lazaretti-Castro, Marise (2014). "An overview on the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis" (PDF). Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia & Metabologia. 58 (2): 162–171. doi:10.1590/0004-2730000003039. ISSN 0004-2730. PMID 24830593. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Majeed, W.; Aslam, B.; Javed, I.; Khaliq, T.; Muhammad, F.; Ali, A.; Raza, A. (2014). "Breast cancer: major risk factors and recent developments in treatment". Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 15 (8): 3353–8. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.8.3353. PMID 24870721.

- ↑ Learning, Jones & Bartlett (14 January 2015). 2015 Nurse's Drug Handbook. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 9781284091373. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 540–. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1.

- ↑ Louis J Denis; Keith Griffiths; Amir V Kaisary; Gerald P Murphy (1 March 1999). Textbook of Prostate Cancer: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment: Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment. CRC Press. pp. 297–. ISBN 978-1-85317-422-3. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Premarin". Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Horský, Jan; Presl, Jiří (1981). "Hormonal Treatment of Disorders of the Menstrual Cycle". In J. Horsky; J. Presl (eds.). Ovarian Function and its Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 309–332. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-8195-9_11. ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ George Morris Piersol (1975). The Cyclopedia of Medicine, Surgery, Specialties. F. A. Davis Company. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ John E. Morley; Lucretia van den Berg (5 November 1999). Endocrinology of Aging. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 172–. ISBN 978-1-59259-715-4. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Ronald I. Shorr (11 April 2007). Drugs for the Geriatric Patient E-Book: Text with BONUS Handheld Software. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 462–. ISBN 978-1-4377-1035-9. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 3 Bińkowska M (October 2014). "Menopausal hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism". Prz Menopauzalny. 13 (5): 267–72. doi:10.5114/pm.2014.46468. PMC 4520375. PMID 26327865.

- ↑ Smith NL, Blondon M, Wiggins KL, Harrington LB, van Hylckama Vlieg A, Floyd JS, Hwang M, Bis JC, McKnight B, Rice KM, Lumley T, Rosendaal FR, Heckbert SR, Psaty BM (January 2014). "Lower risk of cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women taking oral estradiol compared with oral conjugated equine estrogens". JAMA Intern Med. 174 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11074. PMC 4636198. PMID 24081194.

- ↑ Smith NL, Heckbert SR, Lemaitre RN, Reiner AP, Lumley T, Weiss NS, Larson EB, Rosendaal FR, Psaty BM (October 2004). "Esterified estrogens and conjugated equine estrogens and the risk of venous thrombosis". JAMA. 292 (13): 1581–7. doi:10.1001/jama.292.13.1581. PMID 15467060.

- ↑ Lekovic D, Miljic P, Dmitrovic A, Thachil J (May 2017). "How do you decide on hormone replacement therapy in women with risk of venous thromboembolism?". Blood Rev. 31 (3): 151–157. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2016.12.001. PMID 27998619.

- ↑ Roach RE, Lijfering WM, Helmerhorst FM, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, van Hylckama Vlieg A (January 2013). "The risk of venous thrombosis in women over 50 years old using oral contraception or postmenopausal hormone therapy". J. Thromb. Haemost. 11 (1): 124–31. doi:10.1111/jth.12060. PMID 23136837. S2CID 22306721.

- ↑ H.J. Buchsbaum (6 December 2012). The Menopause. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-1-4612-5525-3. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Tommaso Falcone; William W. Hurd (22 May 2013). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery: A Practical Guide. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-4614-6837-0.

- ↑ Joseph S. Sanfilippo (January 1998). Primary Care in Obstetrics and Gynecology: A Handbook for Clinicians. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 220, 227. ISBN 978-0-387-94739-6.

Conjugated estrogens are absorbed with peak levels at 4 hours and a half-life of approximately 12 hours.

- ↑ Cline JM (2007). "Assessing the mammary gland of nonhuman primates: effects of endogenous hormones and exogenous hormonal agents and growth factors". Birth Defects Research Part B: Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology. 80 (2): 126–46. doi:10.1002/bdrb.20112. PMID 17443713.

- 1 2 3 4 Notelovitz M (March 2006). "Clinical opinion: the biologic and pharmacologic principles of estrogen therapy for symptomatic menopause". MedGenMed. 8 (1): 85. PMC 1682006. PMID 16915215.

- 1 2 Nachtigall LE, Raju U, Banerjee S, Wan L, Levitz M (2000). "Serum estradiol-binding profiles in postmenopausal women undergoing three common estrogen replacement therapies: associations with sex hormone-binding globulin, estradiol, and estrone levels". Menopause. 7 (4): 243–50. doi:10.1097/00042192-200007040-00006. ISSN 1072-3714. PMID 10914617. S2CID 3076514.

- ↑ Lauritzen C (September 1990). "Clinical use of oestrogens and progestogens". Maturitas. 12 (3): 199–214. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(90)90004-P. PMID 2215269.

- ↑ Lauritzen C (June 1977). "[Estrogen thearpy in practice. 3. Estrogen preparations and combination preparations]" [Estrogen therapy in practice. 3. Estrogen preparations and combination preparations]. Fortschritte Der Medizin (in Deutsch). 95 (21): 1388–92. PMID 559617.

- ↑ Wolf AS, Schneider HP (12 March 2013). Östrogene in Diagnostik und Therapie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-3-642-75101-1.

- ↑ Göretzlehner G, Lauritzen C, Römer T, Rossmanith W (1 January 2012). Praktische Hormontherapie in der Gynäkologie. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-3-11-024568-4.

- ↑ Knörr K, Beller FK, Lauritzen C (17 April 2013). Lehrbuch der Gynäkologie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-3-662-00942-0.

- ↑ Horský J, Presl J (1981). "Hormonal Treatment of Disorders of the Menstrual Cycle". In Horsky J, Presl J (eds.). Ovarian Function and its Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 309–332. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-8195-9_11. ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9.

- ↑ Pschyrembel W (1968). Praktische Gynäkologie: für Studierende und Ärzte. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 598–599. ISBN 978-3-11-150424-7.

- ↑ Lauritzen CH (January 1976). "The female climacteric syndrome: significance, problems, treatment". Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. Supplement. 51: 47–61. doi:10.3109/00016347509156433. PMID 779393.

- ↑ Lauritzen C (1975). "The Female Climacteric Syndrome: Significance, Problems, Treatment". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 54 (s51): 48–61. doi:10.3109/00016347509156433. ISSN 0001-6349.

- ↑ Kopera H (1991). "Hormone der Gonaden". Hormonelle Therapie für die Frau. Kliniktaschenbücher. pp. 59–124. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-95670-6_6. ISBN 978-3-540-54554-5. ISSN 0172-777X.

- ↑ Scott WW, Menon M, Walsh PC (April 1980). "Hormonal Therapy of Prostatic Cancer". Cancer. 45 Suppl 7: 1929–1936. doi:10.1002/cncr.1980.45.s7.1929. PMID 29603164.

- ↑ Leinung MC, Feustel PJ, Joseph J (2018). "Hormonal Treatment of Transgender Women with Oral Estradiol". Transgender Health. 3 (1): 74–81. doi:10.1089/trgh.2017.0035. PMC 5944393. PMID 29756046.

- ↑ Ryden AB (1950). "Natural and synthetic oestrogenic substances; their relative effectiveness when administered orally". Acta Endocrinologica. 4 (2): 121–39. doi:10.1530/acta.0.0040121. PMID 15432047.

- ↑ Ryden AB (1951). "The effectiveness of natural and synthetic oestrogenic substances in women". Acta Endocrinologica. 8 (2): 175–91. doi:10.1530/acta.0.0080175. PMID 14902290.

- ↑ Kottmeier HL (1947). "Ueber blutungen in der menopause: Speziell der klinischen bedeutung eines endometriums mit zeichen hormonaler beeinflussung: Part I". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 27 (s6): 1–121. doi:10.3109/00016344709154486. ISSN 0001-6349.

There is no doubt that the conversion of the endometrium with injections of both synthetic and native estrogenic hormone preparations succeeds, but the opinion whether native, orally administered preparations can produce a proliferation mucosa changes with different authors. PEDERSEN-BJERGAARD (1939) was able to show that 90% of the folliculin taken up in the blood of the vena portae is inactivated in the liver. Neither KAUFMANN (1933, 1935), RAUSCHER (1939, 1942) nor HERRNBERGER (1941) succeeded in bringing a castration endometrium into proliferation using large doses of orally administered preparations of estrone or estradiol. Other results are reported by NEUSTAEDTER (1939), LAUTERWEIN (1940) and FERIN (1941); they succeeded in converting an atrophic castration endometrium into an unambiguous proliferation mucosa with 120–300 oestradiol or with 380 oestrone.

- ↑ Rietbrock N, Staib AH, Loew D (11 March 2013). Klinische Pharmakologie: Arzneitherapie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 426–. ISBN 978-3-642-57636-2.

- ↑ Martinez-Manautou J, Rudel HW (1966). "Antiovulatory Activity of Several Synthetic and Natural Estrogens". In Robert Benjamin Greenblatt (ed.). Ovulation: Stimulation, Suppression, and Detection. Lippincott. pp. 243–253.

- ↑ Herr F, Revesz C, Manson AJ, Jewell JB (1970). "Biological Properties of Estrogen Sulfates". Chemical and Biological Aspects of Steroid Conjugation. pp. 368–408. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-49793-3_8. ISBN 978-3-642-49506-9.

- ↑ Duncan CJ, Kistner RW, Mansell H (October 1956). "Suppression of ovulation by trip-anisyl chloroethylene (TACE)". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 8 (4): 399–407. PMID 13370006.

- 1 2 3 Shearer RJ, Hendry WF, Sommerville IF, Fergusson JD (December 1973). "Plasma testosterone: an accurate monitor of hormone treatment in prostatic cancer". Br J Urol. 45 (6): 668–77. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1973.tb12238.x. PMID 4359746.

- ↑ Jorge Martinez-Manautou; Harry W. Rudel (1966). "Antiovulatory Activity of Several Synthetic and Natural Estrogens". In Robert Benjamin Greenblatt (ed.). Ovulation: Stimulation, Suppression, and Detection. Lippincott. pp. 243–253. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Herr, F.; Revesz, C.; Manson, A. J.; Jewell, J. B. (1970). "Biological Properties of Estrogen Sulfates". Chemical and Biological Aspects of Steroid Conjugation. pp. 368–408. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-49793-3_8. ISBN 978-3-642-49506-9.

- ↑ Scott WW, Menon M, Walsh PC (April 1980). "Hormonal Therapy of Prostatic Cancer". Cancer. 45 Suppl 7: 1929–1936. doi:10.1002/cncr.1980.45.s7.1929. PMID 29603164. S2CID 4492779.

- 1 2 3 Fotherby K (August 1996). "Bioavailability of orally administered sex steroids used in oral contraception and hormone replacement therapy". Contraception. 54 (2): 59–69. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(96)00136-9. PMID 8842581.

- 1 2 3 4 Rogerio A. Lobo (5 June 2007). Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Academic Press. pp. 771–. ISBN 978-0-08-055309-2. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ M. Notelovitz; P.A. van Keep (6 December 2012). The Climacteric in Perspective: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress on the Menopause, held at Lake Buena Vista, Florida, October 28–November 2, 1984. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 395–. ISBN 978-94-009-4145-8. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ G. E. Seidel (1974). Gonadotrophins: Current Research. Ardent Media. pp. 157–. ISBN 978-0-8422-7205-6. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Punnonen R, Vilska S, Grönroos M, Rauramo L (December 1980). "The vaginal absorption of oestrogens in post-menopausal women". Maturitas. 2 (4): 321–6. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(80)90034-1. PMID 7231202.

- ↑ Honjo H, Kitawaki J, Itoh M, Yasuda J, Iwasaku K, Urabe M, Naitoh K, Yamamoto T, Okada H, Ohkubo T (1987). "Serum and urinary estrone sulfate during the menstrual cycle, measured by a direct radioimmunoassay, and fate of exogenously injected estrone sulfate". Horm Res. 27 (2): 61–8. doi:10.1159/000180788. PMID 3653846.

- 1 2 3 Wallach, Edward E.; Hammond, Charles B.; Maxson, Wayne S. (1982). "Current status of estrogen therapy for the menopause". Fertility and Sterility. 37 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)45970-4. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 6277697.

- ↑ Bhavnani BR, Tam SP, Lu X (October 2008). "Structure activity relationships and differential interactions and functional activity of various equine estrogens mediated via estrogen receptors (ERs) ERalpha and ERbeta". Endocrinology. 149 (10): 4857–70. doi:10.1210/en.2008-0304. PMID 18599548.

- ↑ Georgina D. Feldberg; Molly Ladd-Taylor; Alison Li (2003). Women, Health and Nation: Canada and the United States Since 1945. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-0-7735-2501-6. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Schachter, B.; Marrian, G. F. (1938). "The isolation of estrone sulfate from the urine of pregnant mares". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 126: 663–669.

- 1 2 3 Jim Kling October 2000 The Strange Case of Premarin Archived 9 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Modern Drug Discovery (3):8 46–52

- ↑ "Federal register [microform]". Washington : [Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration : Distributed by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O.] 3 June 1972 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement. April 2–4, 1984 Osteoporosis Archived 21 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Food and Drug Administration. May 5, 1997 Conjugated Estrogens - Letter from Dr. Janet Woodcock: Approvability of a Synthetic Generic Version of Premarin Archived 23 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Nick Panay; Paula Briggs; Gab Kovacs (20 August 2015). Managing the Menopause. Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-1-107-45182-7.

Premarin (Pregnant Mares Urine) was introduced in Canada in 1941, in the USA in 1942 and in the UK in 1956.

- ↑ "ChemIDplus - 12126-59-9 - QTTMOCOWZLSYSV-QWAPEVOJSA-M - Estrogens, conjugated [USP:JAN] - Similar structures search, synonyms, formulas, resource links, and other chemical information". Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ MaryAnne Hochadel; Jerry Avorn (1 January 2007). The AARP Guide to Pills: Essential Information on More Than 1,200 Prescription and Nonprescription Medications, Including Generics. Sterling Publishing Company Incorporated. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-1-4027-4446-4.

- ↑ Ziel HK, Finkle WD (4 December 1975). "Increased risk of endometrial carcinoma among users of conjugated estrogens". New England Journal of Medicine. 293 (23): 1167–1170. doi:10.1056/NEJM197512042932303. PMID 171569.

- ↑ McDonald TW, et al. (15 March 1977). "Exogenous estrogen and endometrial carcinoma: case-control and incidence study". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 127 (6): 572–580. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(77)90351-9. PMID 190887.

- ↑ Natasha Singer and Duff Wilson (12 December 2009). "Menopause, as Brought to You by Big Pharma". New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Brunner RL et al; Womens Health Initiative Investigators (26 September 2005). "Effects of conjugated equine estrogen on health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized clinical trial". Archives of Internal Medicine. 165 (17): 1976–1986. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.17.1976. PMID 16186467.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Earnings Results for the 2006 Fourth Quarter and Full Year" (PDF) (Press release). Wyeth. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ "Pfizer Statement on Prempro". Indy News Channel. 24 November 2009. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012.

- 1 2 Jef Feeley (24 February 2010). "Pfizer wins trial over claim Prempro caused cancer". Bloomberg.

- ↑ "Pfizer properly warned about Prempro risks, jury finds". 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ "Legal Intelligencer: Philadelphia jury returns defense verdict in HRT case, Amaris Elliott Engel". Archived from the original on 25 March 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ News, Keith Morrison NBC (19 January 2004). "The HRT horses". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

Further reading

- Bhavnani, Bhagu R. (1988). "The Saga of the Ring B Unsaturated Equine Estrogens*". Endocrine Reviews. 9 (4): 396–416. doi:10.1210/edrv-9-4-396. ISSN 0163-769X. PMID 3065072.

- Ansbacher R (April 1993). "Bioequivalence of conjugated estrogen products". Clin Pharmacokinet. 24 (4): 271–4. doi:10.2165/00003088-199324040-00001. PMID 8387902. S2CID 7681617.

- O'Connell MB (September 1995). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacologic variation between different estrogen products". J Clin Pharmacol. 35 (9 Suppl): 18S–24S. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb04143.x. PMID 8530713. S2CID 10159196.

- Egarter C, Geurts P, Boschitsch E, Speiser P, Huber J (April 1996). "The effects of estradiol valerate plus medroxyprogesterone acetate and conjugated estrogens plus medrogestone on climacteric symptoms and metabolic variables in perimenopausal women". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 75 (4): 386–93. doi:10.3109/00016349609033337. PMID 8638462. S2CID 44498140.

- Bhavnani BR (January 1998). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of conjugated equine estrogens: chemistry and metabolism". Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 217 (1): 6–16. doi:10.3181/00379727-217-44199. PMID 9421201. S2CID 45177839.

- Gruber DM, Huber JC (December 1999). "Conjugated estrogens--the natural SERMs". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 13 Suppl 6: 9–12. PMID 10862263.

- Campagnoli C, Ambroggio S, Biglia N, Sismondi P (December 1999). "Conjugated estrogens and breast cancer risk". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 13 Suppl 6: 13–9. PMID 10862264.

- Bhavnani BR (June 2003). "Estrogens and menopause: pharmacology of conjugated equine estrogens and their potential role in the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 85 (2–5): 473–82. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00220-6. PMID 12943738. S2CID 45552896.

- Ortmann J, Traupe T, Vetter W, Barton M (May 2004). "[Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy and cardiovascular risk: role of conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate]". Praxis (in Deutsch). 93 (21): 904–14. doi:10.1024/0369-8394.93.21.904. PMID 15216975.

- Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. S2CID 24616324. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- Kurabayashi T (November 2007). "[New evidence of conjugated estrogen and 17beta-estradiol for treatment and prevention of osteoporosis]". Nippon Rinsho (in 日本語). 65 Suppl 9: 369–73. PMID 18161134.

- Lamba G, Kaur H, Adapa S, Shah D, Malhotra BK, Rafiyath SM, Thakar K, Fernandez AC (June 2013). "Use of conjugated estrogens in life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding in hemodialysis patients--a review". Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 19 (3): 334–7. doi:10.1177/1076029612437575. PMID 22411999. S2CID 30468265.

- Mirkin S, Komm BS, Pickar JH (January 2014). "Conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms: a review of safety data". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 13 (1): 45–56. doi:10.1517/14740338.2013.824965. PMID 23919270. S2CID 24379298.

- Bhavnani BR, Stanczyk FZ (July 2014). "Pharmacology of conjugated equine estrogens: efficacy, safety and mechanism of action". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 142: 16–29. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.10.011. PMID 24176763. S2CID 1360563.

- Mattison DR, Karyakina N, Goodman M, LaKind JS (2014). "Pharmaco- and toxicokinetics of selected exogenous and endogenous estrogens: a review of the data and identification of knowledge gaps". Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 44 (8): 696–724. doi:10.3109/10408444.2014.930813. PMID 25099693. S2CID 11212469.

External links

- "Estrogens, conjugated". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- "Steroidal estrogens". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- WHI Follow-up Study Confirms Health Risks of Long-Term Combination Hormone Therapy Outweigh Benefits for Postmenopausal Women NIH press release, March 4, 2008