Neisseria gonorrhoeae

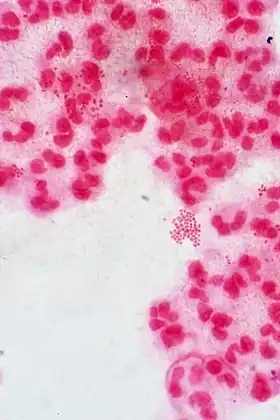

{{ |image =Gonococcal urethritis PHIL 4085 lores.jpg |image_alt =Gram-stain of gonococcal urethritis. Note distribution in neutrophils and presence of both intracellular and extracellular bacteria. (CDC) |image_caption =Gram-stain of gonococcal urethritis. Note distribution in neutrophils and presence of both intracellular and extracellular bacteria. (CDC) |genus =Neisseria |species =gonorrhoeae |authority =(Zopf 1885) Trevisan 1885[1] |synonyms =* Micrococcus der Gonorrhoe Neisser 1879[2]

- Gonococcus neisseri Lindau 1898

|synonyms_ref =

}}

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, also known as gonococcus (singular), or gonococci (plural), is a species of Gram-negative diplococci bacteria isolated by Albert Neisser in 1879.[3] It causes the sexually transmitted genitourinary infection gonorrhea[4] as well as other forms of gonococcal disease including disseminated gonococcemia, septic arthritis, and gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum.

It is oxidase positive and aerobic, and it survives phagocytosis and grows inside neutrophils.[4] Culturing it requires carbon dioxide supplementation and enriched agar (chocolate agar) with various antibiotics (Thayer–Martin). It exhibits antigenic variation through genetic recombination of its pili and surface proteins that interact with the immune system.[3]

Sexual transmission is through vaginal, anal, or oral sex.[5] Sexual transmission may be prevented through the use of barrier protection.[6] Perinatal transmission may occur during childbirth, and may be prevented by antibiotic treatment of the mother before birth and the application of antibiotic eye gel on the eyes of the newborn.[6] After an episode of gonococcal infection, infected persons do not develop immunity to future infections. Reinfection is possible due to N. gonorrhoeae's ability to evade the immune system by varying its surface proteins.[7]

N. gonorrhoeae can cause infection of the genitals, throat, and eyes.[8] Asymptomatic infection is common in males and females.[6][9] Untreated infection may spread to the rest of the body (disseminated gonorrhea infection), especially the joints (septic arthritis). Untreated infection in women may cause pelvic inflammatory disease and possible infertility due to the resulting scarring.[8] Diagnosis is through culture, Gram stain, or nucleic acid tests, such as polymerase chain reaction, of a urine sample, urethral swab, or cervical swab.[10][11] Chlamydia co-testing and testing for other STIs is recommended due to high rates of co-infection.[12]

Antibiotic resistance in N. gonorrhoeae is a growing public health concern, especially given its propensity to develop resistance easily. [13]

Microbiology

Neisseria species are fastidious, Gram-negative cocci that require nutrient supplementation to grow in laboratory cultures. Neisseria spp. are facultatively intracellular and typically appear in pairs (diplococci), resembling the shape of coffee beans. Neisseria is non-spore-forming, capable of moving using twitching motility, and an obligate aerobe (requires oxygen to grow). Of the 11 species of Neisseria that colonize humans, only two are pathogens. N. gonorrhoeae is the causative agent of gonorrhea and N. meningitidis is one cause of bacterial meningitis.[14]

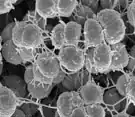

Phenotypic variants of N. gonorrhoeae

Phenotypic variants of N. gonorrhoeae A Gram stain of a urethral exudate showing typical intracellular Gram-negative diplococci, which is diagnostic for gonococcal urethritis

A Gram stain of a urethral exudate showing typical intracellular Gram-negative diplococci, which is diagnostic for gonococcal urethritis

Culture and identification

N. gonorrhoeae is usually isolated on Thayer–Martin agar (or VPN) agar in an atmosphere enriched with 3-7% carbon dioxide.[10] Thayer–Martin agar is a chocolate agar plate (heated blood agar) containing nutrients and antimicrobials (vancomycin, colistin, nystatin, and trimethoprim). This agar preparation facilitates the growth of Neisseria species while inhibiting the growth of contaminating bacteria and fungi. Martin Lewis and New York City agar are other types of selective chocolate agar commonly used for Neisseria growth.[10] N. gonorrhoeae is oxidase positive (possessing cytochrome c oxidase) and catalase positive (able to convert hydrogen peroxide to oxygen).[10] When incubated with the carbohydrates lactose, maltose, sucrose, and glucose, N. gonorrhoeae will oxidize only the glucose.[10]

Surface molecules

On its surface, N. gonorrhoeae bears hair-like pili, surface proteins with various functions, and sugars called lipooligosaccharides. The pili mediate adherence, movement, and DNA exchange. The Opa proteins interact with the immune system, as do the porins. Lipooligosaccharide (LOS) is an endotoxin that provokes an immune response. All are antigenic and all exhibit antigenic variation (see below). The pili exhibit the most variation. The pili, Opa proteins, porins, and even the LOS have mechanisms to inhibit the immune response, making asymptomatic infection possible.[15]

Dynamic polymeric protein filaments called type IV pili allow N. gonorrhoeae to adhere to and move along surfaces. To enter the host the bacteria uses the pili to adhere to and penetrate mucosal surfaces.[4] The pili are a necessary virulence factor for N. gonorrhoeae; without them, the bacterium is unable to cause infection.[8] To move, individual bacteria use their pili like a grappling hook: first, they are extended from the cell surface and attach to a substrate. Subsequent pilus retraction drags the cell forward. The resulting movement is referred to as twitching motility.[16] N. gonorrhoeae is able to pull 100,000 times its own weight, and the pili used to do so are amongst the strongest biological motors known to date, exerting one nanonewton.[17] The PilF and PilT ATPase proteins are responsible for powering the extension and retraction of the type IV pilus, respectively.[18][19] The adhesive functions of the gonococcal pilus play a role in microcolony aggregation and biofilm formation.[20] Surface proteins called Opa proteins can be used to bind to receptors on immune cells and prevent an immune response. At least 12 Opa proteins are known and the many permutations of surface proteins make recognizing N. gonorrhoeae and mounting a defense by immune cells more difficult.[21]

Lipooligosaccharide (LOS) is a low-weight version of lipopolysaccharide present on the surfaces of most other Gram-negative bacteria. It is a sugar (saccharide) side chain attached to lipid A (thus "lipo-") in the outer membrane coating the cell wall of the bacteria. The root "oligo" refers to the fact that it is a few sugars shorter than the typical lipopolysaccharide.[4] As an endotoxin, LOS provokes inflammation. The shedding of LOS by the bacteria is responsible for local injury in, for example, pelvic inflammatory disease.[4] Although its main function is as an endotoxin, LOS may disguise itself with host sialic acid and block initiation of the complement cascade.[4]

Antigenic variation

N. gonorrhoeae evades the immune system through a process called antigenic variation.[22] This process allows N. gonorrhoeae to recombine its genes and alter the antigenic determinants (sites where antibodies bind), such as the Type IV pili,[23] that adorn its surface.[4] Simply stated, the chemical composition of molecules is changed due to changes at the genetic level.[7] N. gonorrhoeae is able to vary the composition of its pili, and LOS; of these, the pili exhibit the most antigenic variation due to chromosomal rearrangement.[8][4] The PilS gene is an example of this ability to rearrange as its combination with the PilE gene is estimated to produce over 100 variants of the PilE protein.[7] These changes allow for adjustment to the differences in the local environment at the site of infection, evasion of recognition by targeted antibodies, and contribute to the lack of an effective vaccine.[7]

In addition to the ability to rearrange the genes it already has, it is also naturally competent to acquire new DNA (via plasmids), via its type IV pilus, specifically proteins Pil Q and Pil T.[24] These processes allow N. gonorrhoeae to acquire/spread new genes, disguise itself with different surface proteins, and prevent the development of immunological memory – an ability which has led to antibiotic resistance and has also impeded vaccine development.[25]

Phase variation

Phase variation is similar to antigenic variation, but instead of changes at the genetic level altering the composition of molecules, these genetic changes result in the turning on or off of a gene.[7] Phase variation most often arises from a frameshift in the expressed gene.[7] The Opacity, or Opa, proteins of N. gonorrhoeae rely strictly on phase variation.[7] Every time the bacteria replicate, they may switch multiple Opa proteins on or off through slipped-strand mispairing. That is, the bacteria introduce frameshift mutations that bring genes in or out of frame. The result is that different Opa genes are translated every time.[4] Pili are varied by antigenic variation, but also phase variation.[7] Frameshifts occur in both the pilE and pilC genes, effectively turning off the expression of pili in situations when they are not needed, such as after colonization when N. gonorrhoeae survives within cells as opposed to on their surfaces.[7]

Survival of gonococci

After gonococci invade and transcytose the host epithelial cells, they land in the submucosa, where neutrophils promptly consume them.[4] The pili and Opa proteins on the surface may interfere with phagocytosis,[8] but most gonococci end up in neutrophils. The exudates from infected individuals contain many neutrophils with ingested gonococci. Neutrophils release an oxidative burst of reactive oxygen species in their phagosomes to kill the gonococci.[26] However, a significant fraction of the gonococci can resist killing through the action of their catalase[4] which breaks down reactive oxygen species and is able to reproduce within the neutrophil phagosomes.[27]

Stohl and Seifert showed that the bacterial RecA protein, which mediates repair of DNA damage, plays an important role in gonococcal survival.[28] Michod et al. have suggested that N. gonorrhoeae may replace DNA damaged in neutrophil phagosomes with DNA from neighboring gonococci.[29] The process in which recipient gonococci integrate DNA from neighboring gonococci into their genome is called transformation.[30]

Genome

The genomes of several strains of N. gonorrhoeae have been sequenced. Most of them are about 2.1 Mb in size and encode 2,100 to 2,600 proteins (although most seem to be in the lower range).[31] For instance, strain NCCP11945 consists of one circular chromosome (2,232,025 bp) encoding 2,662 predicted open reading frames (ORFs) and one plasmid (4,153 bp) encoding 12 predicted ORFs. The estimated coding density over the entire genome is 87%, and the average G+C content is 52.4%, values that are similar to those of strain FA1090. The NCCP11945 genome encodes 54 tRNAs and four copies of 16S-23S-5S rRNA operons.[32]

Horizontal gene transfer

In 2011, researchers at Northwestern University found evidence of a human DNA fragment in a N. gonorrhoeae genome, the first example of horizontal gene transfer from humans to a bacterial pathogen.[33][34]

Disease

Symptoms

Symptoms of infection with N. gonorrhoeae differ depending on the site of infection and many infections are asymptomatic independent of sex.[35][15][5] It is important to note that depending on the route of transmission, N. gonorrhoeae may cause infection of the throat (pharyngitis) or infection of the anus/rectum (proctitis).[36][8]

Disseminated gonococcal infections can occur when N. gonorrhoeae enters the bloodstream, often spreading to the joints and causing a rash (dermatitis-arthritis syndrome).[36] Dermatitis-arthritis syndrome results in joint pain (arthritis), tendon inflammation (tenosynovitis), and painless non-pruritic (non-itchy) dermatitis.[8] Disseminated infection and pelvic inflammatory disease in women tend to begin after menses due to reflux during menses, facilitating spread.[36] In rare cases, disseminated infection may cause infection of the meninges of the brain and spinal cord (meningitis) or infection of the heart valves (endocarditis).[36][37]

Male

In symptomatic men, the primary symptom of genitourinary infection is urethritis – burning with urination (dysuria), increased urge to urinate, and a pus-like (purulent) discharge from the penis. The discharge may be foul smelling.[36] If untreated, scarring of the urethra may result in difficulty urinating. Infection may spread from the urethra in the penis to nearby structures, including the testicles (epididymitis/orchitis), or to the prostate (prostatitis).[36][8][38] Men who have had a gonorrhea infection have a significantly increased risk of having prostate cancer.[39]

Female

In symptomatic women, the primary symptoms of genitourinary infection are increased vaginal discharge, burning with urination (dysuria), increased urge to urinate, pain with intercourse, or menstrual abnormalities. Pelvic inflammatory disease results if N. gonorrhoeae ascends into the pelvic peritoneum (via the cervix, endometrium, and fallopian tubes). The resulting inflammation and scarring of the fallopian tubes can lead to infertility and increased risk of ectopic pregnancy.[36] Pelvic inflammatory disease develops in 10 to 20% of the females infected with N. gonorrhoeae.[36]

Neonates (perinatal infection)

In perinatal infection, the primary manifestation is infection of the eye (neonatal conjunctivitis or ophthalmia neonatorum) when the newborn is exposed to N. gonorrhoeae in the birth canal. The eye infection can lead to corneal scarring or perforation, ultimately resulting in blindness. If the newborn is exposed during birth, conjunctivitis occurs within 2–5 days after birth and is severe.[36][37] Gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum, once common in newborns, is prevented by the application of erythromycin (antibiotic) gel to the eyes of babies at birth as a public health measure. Silver nitrate is no longer used in the United States.[37][36]

Transmission

N. gonorrhoeae is transmitted through vaginal, oral, or anal sex; nonsexual transmission is unlikely in adult infection.[5] It can also be transmitted to the newborn during passage through the birth canal if the mother has untreated genitourinary infection. Given the high rate of asymptomatic infection, all pregnant women should be tested for gonorrhea infection.[5] However, communal baths, towels or fabric, rectal thermometers and caregivers hands have been implicated as means of transmission in the pediatric setting.[40] Kissing has also been implicated as a theoretical means of transmission in the gay male population, based on a newer study.[41]

Traditionally, the bacterium was thought to move attached to spermatozoa, but this hypothesis did not explain female to male transmission of the disease. A recent study suggests that rather than "surf" on wiggling sperm, N. gonorrhoeae bacteria use pili to anchor onto proteins in the sperm and move through coital liquid.[42]

Infection

For N. gonorrhoeae, the first step after successful transmission is adherence to the epithelial cells found at the mucosal site that is infected.[43] The bacterium relies on type IV pili that attach and retract, pulling N. gonorrhoeae toward the epithelial membrane where its surface proteins, such as opacity proteins, can interact directly.[43] After adherence, N. gonorrhoeae replicates itself and forms microcolonies.[44] While colonizing, N. gonorrhoeae has the potential to transcytose across the epithelial barrier and work its way in to the bloodstream.[45] During growth and colonization, N. gonorrhoeae stimulates the release of cytokines and chemokines from host immune cells that are pro-inflammatory.[45] These pro-inflammatory molecules result in the recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils.[7] These phagocytic cells typically take in foreign pathogens and destroy them, but N. gonorrhoeae has evolved many mechanisms that allow it to survive within these immune cells and thwart the attempts at elimination.[7]

Prevention

Transmission is reduced by using latex barriers (e.g. condoms or dental dams) during sex and by limiting sexual partners.[6] Condoms and dental dams should be used during oral and anal sex, as well. Spermicides, vaginal foams, and douches are not effective for prevention of transmission.[4]

Treatment

The current treatment recommended by the CDC is an injected single dose of ceftriaxone (a third-generation cephalosporin).[46] Sexual partners (defined by the CDC as sexual contact within the past 60 days)[11] should also be notified, tested, and treated.[6][46] It is important that if symptoms persist after receiving treatment of N. gonorrhoeae infection, a reevaluation should be pursued.[46]

Antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance in gonorrhea has been noted beginning in the 1940s. Gonorrhea was treated with penicillin, but doses had to be progressively increased to remain effective. By the 1970s, penicillin- and tetracycline-resistant gonorrhea emerged in the Pacific Basin. These resistant strains then spread to Hawaii, California, the rest of the United States, Australia and Europe. Fluoroquinolones were the next line of defense, but soon resistance to this antibiotic emerged, as well. Since 2007, standard treatment has been third-generation cephalosporins, such as ceftriaxone, which are considered to be our "last line of defense".[47][48]Recently, a high-level ceftriaxone-resistant strain of gonorrhea called H041 was discovered in Japan. Lab tests found it to be resistant to high concentrations of ceftriaxone, as well as most of the other antibiotics tested. Within N. gonorrhoeae, genes exist that confer resistance to every single antibiotic used to cure gonorrhea, but thus far they do not coexist within a single gonococcus. However, because of N. gonorrhoeae's high affinity for horizontal gene transfer, antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea is seen as an emerging public health threat.[48]

Serum resistance

As a Gram negative bacteria, N. gonorrhoeae requires defense mechanisms to protect itself against the complement system (or complement cascade), whose components are found with human serum.[15] There are three different pathways that activate this system however, they all result in the activation of complement protein 3 (C3).[49] A cleaved portion of this protein, C3b, is deposited on pathogenic surfaces and results in opsonization as well as the downstream activation of the membrane attack complex.[49] N. gonorrhoeae has several mechanisms to avoid this action.[45] As a whole, these mechanisms are referred to as serum resistance.[45]

History

Name origin

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is named for Albert Neisser, who isolated it as the causative agent of the disease gonorrhea in 1878.[45][3] Galen (130 AD) coined the term "gonorrhea" from the Greek gonos which means "seed" and rhoe which means "flow".[50][7] Thus, gonorrhea means "flow of seed", a description referring to the white penile discharge, assumed to be semen, seen in male infection.[45]

Discovery

In 1878, Albert Neisser isolated and visualized N. gonorrhoeae diplococci in samples of pus from 35 men and women with the classic symptoms of genitourinary infection with gonorrhea – two of whom also had infections of the eyes.[7] In 1882, Leistikow and Loeffler were able to grow the organism in culture.[45] Then in 1883, Max Bockhart proved conclusively that the bacterium isolated by Albert Neisser was the causative agent of the disease known as gonorrhea by inoculating the penis of a healthy man with the bacteria.[7] The man developed the classic symptoms of gonorrhea days after, satisfying the last of Koch's postulates. Until this point, researchers debated whether syphilis and gonorrhea were manifestations of the same disease or two distinct entities.[51][7] One such 18th-century researcher, John Hunter, tried to settle the debate in 1767[7] by inoculating a man with pus taken from a patient with gonorrhea. He erroneously concluded that both syphilis and gonorrhea were indeed the same disease when the man developed the copper-colored rash that is classic for syphilis.[49][51] Although many sources repeat that Hunter inoculated himself,[49][45] others have argued that it was in fact another man.[52] After Hunter's experiment other scientists sought to disprove his conclusions by inoculating other male physicians, medical students,[45] and incarcerated men with gonorrheal pus, who all developed the burning and discharge of gonorrhea. One researcher, Ricord, took the initiative to perform 667 inoculations of gonorrheal pus on patients of a mental hospital, with zero cases of syphilis.[7][45] Notably, the advent of penicillin in the 1940s made effective treatments for gonorrhea available.

See also

References

- ↑ "Neisseria". In: List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). Created by J.P. Euzéby in 1997. Curated by A.C. Parte since 2013. Available on: http://www.bacterio.net Archived 2022-04-01 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ Neisser, Albert (1879). "Ueber eine der Gonorrhoe eigentümliche Micrococusform" [About a micrococus form peculiar to gonorrhea]. Centralblatt für die medizinischen Wissenschaften (in Deutsch). 17 (28): 497–500.

- 1 2 3 O'Donnell, Judith A.; Gelone, Steven P. (2009). Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438101590. Archived from the original on 2023-04-03. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Ryan, KJ; Ray, CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0. Archived from the original on 2023-04-03. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- 1 2 3 4 "Detailed STD Facts - Gonorrhea". www.cdc.gov. 2017-09-26. Archived from the original on 2016-09-02. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/clinical.htm Archived 2015-06-09 at the Wayback Machine section on prevention methods

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Hill, Stuart A.; Masters, Thao L.; Wachter, Jenny (5 September 2016). "Gonorrhea – an evolving disease of the new millennium". Microbial Cell. 3 (9): 371–389. doi:10.15698/mic2016.09.524. PMC 5354566. PMID 28357376.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Levinson, Warren (2014). Review of medical microbiology and immunology. ISBN 978-0-07-181811-7. OCLC 871305336.

- ↑ "Final Recommendation Statement: Chlamydia and Gonorrhea: Screening - US Preventive Services Task Force". www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Archived from the original on 2020-03-17. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ng, Lai-King; Martin, Irene E (2005). "The Laboratory Diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae". Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 16 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1155/2005/323082. PMC 2095009. PMID 18159523.

- 1 2 "Gonococcal Infections - 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines". 2018-01-04. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ↑ Birgit., MacKenzie, Colin R. Henrich (2012). Diagnosis of sexually transmitted diseases : methods and protocols. Humana Press. ISBN 9781617799365. OCLC 781681739.

- ↑ Quillin, Sarah Jane; Seifert, H. Steven (April 2018). "Neisseria gonorrhoeae host adaptation and pathogenesis". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 16 (4): 226–240. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2017.169. ISSN 1740-1534. Archived from the original on 2023-02-01. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ↑ Ladhani SN, Lucidarme J, Parikh SR, Campbell H, Borrow R, Ramsay ME (June 2020). "Meningococcal disease and sexual transmission: urogenital and anorectal infections and invasive disease due to Neisseria meningitidis". Lancet. 395 (10240): 1865–1877. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30913-2. PMID 32534649. S2CID 219701418.

- 1 2 3 Edwards, Jennifer L.; Apicella, Michael A. (October 2004). "The Molecular Mechanisms Used by Neisseria gonorrhoeae To Initiate Infection Differ between Men and Women". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 17 (4): 965–981. doi:10.1128/CMR.17.4.965-981.2004. PMC 523569. PMID 15489357.

- ↑ Merz, Alexey J.; So, Magdalene; Sheetz, Michael P. (September 2000). "Pilus retraction powers bacterial twitching motility". Nature. 407 (6800): 98–102. Bibcode:2000Natur.407...98M. doi:10.1038/35024105. PMID 10993081. S2CID 4425775.

- ↑ Biais N, Ladoux B, Higashi D, So M, Sheetz M (2008). "Cooperative retraction of bundled type IV pili enables nanonewton force generation". PLOS Biol. 6 (4): e87. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060087. PMC 2292754. PMID 18416602.

- ↑ Freitag, Nancy E.; Seifert, H. Steven; Koomey, Michael (May 1995). "Characterization of the pilF?pilD pilus-assembly locus of Neisseria gonorrhoeae". Molecular Microbiology. 16 (3): 575–586. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02420.x. hdl:2027.42/72746. PMID 7565116. S2CID 24580638.

- ↑ Jakovljevic, Vladimir; Leonardy, Simone; Hoppert, Michael; Søgaard-Andersen, Lotte (April 2008). "PilB and PilT Are ATPases Acting Antagonistically in Type IV Pilus Function in Myxococcus xanthus". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (7): 2411–2421. doi:10.1128/JB.01793-07. PMC 2293208. PMID 18223089.

- ↑ Xu J, Seifert HS (November 2018). "Analysis of Pilin Antigenic Variation in Neisseria meningitidis by Next-Generation Sequencing". Journal of Bacteriology. 200 (22). doi:10.1128/JB.00465-18. PMC 6199478. PMID 30181126.

- ↑ STI Awareness: Gonorrhea Archived 2012-03-31 at the Wayback Machine. Planned Parenthood Advocates of Arizona. 11 April 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ↑ Stern, Anne; Brown, Melissa; Nickel, Peter; Meyer, Thomas F. (1986). "Opacity genes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Control of phase and antigenic variation". Cell. 47 (1): 61–71. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(86)90366-1. PMID 3093085. S2CID 21366517.

- ↑ Cahoon, Laty A.; Seifert, H. Steven (September 2011). "Focusing homologous recombination: pilin antigenic variation in the pathogenic Neisseria: Pilin antigenic variation". Molecular Microbiology. 81 (5): 1136–1143. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07773.x. PMC 3181079. PMID 21812841.

- ↑ Obergfell, Kyle P.; Seifert, H. Steven (27 February 2015). "Mobile DNA in the Pathogenic Neisseria". Microbiology Spectrum. 3 (1). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.MDNA3-0015-2014. PMC 4389775. PMID 25866700.

- ↑ Aas, Finn Erik; Wolfgang, Matthew; Frye, Stephan; Dunham, Steven; Løvold, Cecilia; Koomey, Michael (2002). "Competence for natural transformation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Components of DNA binding and uptake linked to type IV pilus expression". Molecular Microbiology. 46 (3): 749–60. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03193.x. PMID 12410832. S2CID 21854666.

- ↑ Simons, M. P.; Nauseef, W. M.; Apicella, M. A. (2005). "Interactions of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with Adherent Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes". Infection and Immunity. 73 (4): 1971–7. doi:10.1128/iai.73.4.1971-1977.2005. PMC 1087443. PMID 15784537.

- ↑ Escobar A, Rodas PI, Acuña-Castillo C (2018). "Macrophage-Neisseria gonorrhoeae Interactions: A Better Understanding of Pathogen Mechanisms of Immunomodulation". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 3044. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.03044. PMC 6309159. PMID 30627130.

- ↑ Stohl, E. A.; Seifert, H. S. (2006). "Neisseria gonorrhoeae DNA Recombination and Repair Enzymes Protect against Oxidative Damage Caused by Hydrogen Peroxide". Journal of Bacteriology. 188 (21): 7645–51. doi:10.1128/JB.00801-06. PMC 1636252. PMID 16936020.

- ↑ Michod, Richard E.; Bernstein, Harris; Nedelcu, Aurora M. (May 2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 267–285. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550.

- ↑ Blokesch M (November 2016). "Natural competence for transformation". Current Biology. 26 (21): R1126–R1130. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.058. PMID 27825443.

- ↑ "Neisseria gonorrhoeae genome statistics". Broad Institute. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ Chung, G. T.; Yoo, J. S.; Oh, H. B.; Lee, Y. S.; Cha, S. H.; Kim, S. J.; Yoo, C. K. (2008). "Complete genome sequence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae NCCP11945". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (17): 6035–6. doi:10.1128/JB.00566-08. PMC 2519540. PMID 18586945.

- ↑ Anderson, Mark T.; Seifert, H. Steven (2011). "Neisseria gonorrhoeae and humans perform an evolutionary LINE dance". Mobile Genetic Elements. 1 (1): 85–87. doi:10.4161/mge.1.1.15868. PMC 3190277. PMID 22016852.

- ↑ Anderson, M. T.; Seifert, H. S. (2011). "Opportunity and Means: Horizontal Gene Transfer from the Human Host to a Bacterial Pathogen". mBio. 2 (1): e00005–11. doi:10.1128/mBio.00005-11. PMC 3042738. PMID 21325040.

- ↑ Detels, Roger; Green, Annette M.; Klausner, Jeffrey D.; Katzenstein, David; Gaydos, Charlotte; Hadsfield, Hunter; Peqyegnat, Willo; Mayer, Kenneth; Hartwell, Tyler D.; Quinn, Thomas . (2011). "The Incidence and Correlates of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae Infections in Selected Populations in Five Countries". Sex. Transm. Dis. 38 (6): 503–509. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318206c288. PMC 3408314. PMID 22256336.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ryan, KJ; Ray, CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0. Archived from the original on 2023-04-03. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- 1 2 3 "Gonococcal Infections - 2015 STD Treatment Guidelines". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ↑ "Gonorrhea (the clap) Symptoms". std-gov.org. 2015-04-02. Archived from the original on 2022-11-29. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ↑ Caini, Saverio; Gandini, Sara; Dudas, Maria; Bremer, Viviane; Severi, Ettore; Gherasim, Alin (August 2014). "Sexually transmitted infections and prostate cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Cancer Epidemiology. 38 (4): 329–338. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2014.06.002. PMID 24986642.

- ↑ Goodyear-Smith, Felicity (November 2007). "What is the evidence for non-sexual transmission of gonorrhoea in children after the neonatal period? A systematic review". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 14 (8): 489–502. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2007.04.001. PMID 17961874.

- ↑ Bever, Lindsey (10 May 2019). "You May Not Need to Have Sex to Transmit Gonorrhea, New Study Suggests". ScienceAlert. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ↑ Anderson, Mark T.; Dewenter, Lena; Maier, Berenike; Seifert, H. Steven (May 2014). "Seminal Plasma Initiates a Neisseria gonorrhoeae Transmission State". mBio. 5 (2): e01004-13. doi:10.1128/mBio.01004-13. PMC 3958800. PMID 24595372.

- 1 2 Pearce, W A; Buchanan, T M (1 April 1978). "Attachment role of gonococcal pili. Optimum conditions and quantitation of adherence of isolated pili to human cells in vitro". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 61 (4): 931–943. doi:10.1172/JCI109018. PMC 372611. PMID 96134.

- ↑ Higashi, Dustin L.; Lee, Shaun W.; Snyder, Aurelie; Weyand, Nathan J.; Bakke, Antony; So, Magdalene (October 2007). "Dynamics of Neisseria gonorrhoeae Attachment: Microcolony Development, Cortical Plaque Formation, and Cytoprotection". Infection and Immunity. 75 (10): 4743–4753. doi:10.1128/IAI.00687-07. PMC 2044525. PMID 17682045.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Quillin, Sarah Jane; Seifert, H Steven (April 2018). "Neisseria gonorrhoeae host adaptation and pathogenesis". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 16 (4): 226–240. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2017.169. PMC 6329377. PMID 29430011.

- 1 2 3 "CDC - Gonorrhea Treatment". www.cdc.gov. 2021-07-22. Archived from the original on 2010-09-28. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ↑ "UK doctors advised gonorrhoea has turned drug resistant". BBC News. 10 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- 1 2 STI Awareness: Antibiotic-Resistant Gonorrhea Archived 2012-11-05 at the Wayback Machine. Planned Parenthood Advocates of Arizona. 6 March 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Charles A Janeway, Jr; Travers, Paul; Walport, Mark; Shlomchik, Mark J. (2001). "The complement system and innate immunity". Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. 5th Edition. Archived from the original on 2023-03-30. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ↑ "gonorrhea | Origin and meaning of gonorrhea by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-05. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- 1 2 Singal, Archana; Grover, Chander (2016). Comprehensive Approach to Infections in Dermatology. JP Medical. p. 470. ISBN 978-93-5152-748-0.

- ↑ Gladstein, J. (1 July 2005). "Hunter's Chancre: Did the Surgeon Give Himself Syphilis?". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (1): 128, author reply 128–9. doi:10.1086/430834. PMID 15937780.

External links

- Todar, Kenneth. "Pathogenic Neisseriae: Gonorrhea, Neonatal Ophthalmia and Meningococcal Meningitis". Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology. Archived from the original on 2022-10-16. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- Gonorrhea at eMedicine

- "Neisseria gonorrhoeae". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 485. Archived from the original on 2022-04-26. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- Type strain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae at BacDive – the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Archived 2021-07-30 at the Wayback Machine