Shigella sonnei

| Shigella sonnei | |

|---|---|

| |

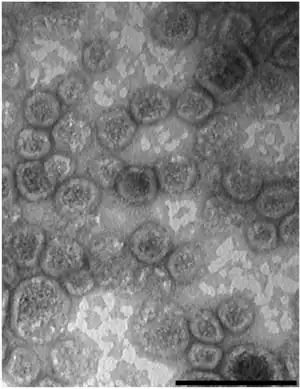

| Gram negative Shigella sonnei bacteria which spent 48 hours cultured on Hektoen enteric agar (HEK). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Enterobacterales |

| Family: | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Shigella |

| Species: | S. sonnei |

| Binomial name | |

| Shigella sonnei (Levine 1920) Weldin 1927 [1] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Bacterium sonnei Levine 1920 | |

Shigella sonnei is a species of Shigella.[2] Together with Shigella flexneri, it is responsible for 90% of shigellosis cases.[3] Shigella sonnei is named for the Danish bacteriologist Carl Olaf Sonne.[4][5] It is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped, nonmotile, non-spore-forming bacterium.[6]

This species polymerizes host cell actin.

Transmission

"Group D" Shigella bacteria cause shigellosis. Those infected with the bacteria release it into their stool, thus causing possibility of spread through food or water, or from direct contact to a person orally. Having poorly sanitized living conditions or contaminated food or water contributes to contracting the disease.[7]

Evolution

This species is clonal and has spread worldwide. Analysis of 132 strains has shown that they originated from a common ancestor in Europe around 1500 AD.[8]

Growth in lab

It can be grown on MAC agar and TSA, at 37 °C optimally, but it also grows at 25 °C. It is facultatively anaerobic and chemo-organotrophic, and produces acid when carbohydrates are catabolized.

Infection

Symptoms and signs

Infections can result in acute fever, acute abdominal cramping, cramping rectal pain, nausea, watery diarrhea, or blood, mucus, or pus in the stool, which may occur within 1–7 days after coming in contact with the bacteria.[7] Most Shigella infection usually clears up without complications, but if left untreated or delay in diagnosis may lead to some serious complication such as dehydration (especially severe dehydration can lead to shock and death), seizure, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), toxic megacolon, and reactive arthritis.[9] Persons with diarrhea usually recover completely, although it may be several months before their bowel habits are entirely normal. Once someone has had shigellosis, they are not likely to get infected with that specific type again for at least several years. However, they can still get infected with other types of Shigella.[10]

Possible complications

- Dehydration

- Seizures occur most often in children, although how Shigella causes this complications is unknown.

- Bloodstream infections may occur from Shigella.

- Rectal prolapse can occur while straining during bowel movements.

- Toxic megacolon paralyzes bowel movements or causes passing gas.

- Reactive arthritis, which is the inflammation of joints[11]

- Hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) is a complication that occurs when bacteria enter the digestive system and produce toxins to destroy red blood cells that may cause bloody diarrhea as a symptom.

Risk factor

Infants and toddlers, the elderly, and people living with chronic health conditions are all susceptible to the most severe symptoms of S. sonnei disease. Shigellosis is commonly suffered by individuals with advanced HIV disease, as well as men who have sex with men, regardless of their HIV status. Shigellosis may invade the bloodstream and cause bacteremia in people with a compromised immune system, which can be life-threatening.[12][13]

Prevention

No vaccines are available for Shigella. The best prevention against shigellosis is thorough, frequent, and cautious handwashing with soap and water before and after using the washroom and before handling food; also, a strict adherence to standard food and water safety precautions is important. Avoid having sexual intercourse with those people who have diarrhea or who recently recovered from diarrhea. It is also important to avoid swallowing water from ponds, lakes, or untreated swimming pools.[14][15]

Treatment

Antibiotic resistance has been reported.[16]

References

- ↑ Parte, A.C. "Shigella". LPSN. Archived from the original on 2022-01-26. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ↑ Shigella+sonnei at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ↑ Shigellosis~clinical at eMedicine

- ↑ Carl Olaf Sonne at Who Named It?

- ↑ Shigella sonnei at Who Named It?

- ↑ "Shigella sonnei". Microbewiki. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- 1 2 MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Shigellosis

- ↑ Holt, Kathryn E; Baker, Stephen; Weill, François-Xavier; Holmes, Edward C; Kitchen, Andrew; Yu, Jun; Sangal, Vartul; Brown, Derek J; Coia, John E; Kim, Dong Wook; Choi, Seon Young; Kim, Su Hee; da Silveira, Wanderley D; Pickard, Derek J; Farrar, Jeremy J; Parkhill, Julian; Dougan, Gordon; Thomson, Nicholas R (2012). "Shigella sonnei genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis indicate recent global dissemination from Europe". Nature Genetics. 44 (9): 1056–9. doi:10.1038/ng.2369. PMC 3442231. PMID 22863732.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Staff. "Shigella Infection Archived 2017-09-15 at the Wayback Machine". Shigella Infection Complications. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 24 August 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ CDC Staff" Archived 2017-04-16 at the Wayback Machine"

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Staff. "Shigella Infection" Archived 2017-09-15 at the Wayback Machine. Shigella Infection Complications. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 24 August 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ "Bad Bug Book 2d ed. – BBB – Shigella spp., Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins Handbook, FDA". Archived from the original on 2019-04-22. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ↑ "General Information | Shigella – Shigellosis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2017-10-12. Archived from the original on 2017-04-16. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ↑ "General Information | Shigella – Shigellosis | CDC". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ↑ "Shigellosis – Chapter 3 – 2016 Yellow Book | Travelers' Health | CDC". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ↑ Jain, Sanjay K.; Gupta, Amita; Glanz, Brian; Dick, James; Siberry, George K. (2005). "Antimicrobial-Resistant Shigella sonnei". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 24 (6): 494–7. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000164707.13624.a7. PMID 15933557.

External links

- Shigella sonnei Archived 2022-01-28 at the Wayback Machine at MicrobeWiki Archived 2015-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Shigella sonnei Archived 2022-04-28 at the Wayback Machine in the NCBI Taxonomy Browser

- Type strain of Shigella sonnei at BacDive – the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Archived 2016-09-17 at the Wayback Machine