Paraldehyde

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2,4,6-Trimethyl-1,3,5-trioxane | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

2,4,6-Trimethyl-1,3,5-trioxane | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.219 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Paraldehyde |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C6H12O3 |

| Molar mass | 132.159 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colourless liquid |

| Odor | Sweet |

| Density | 0.996 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 12 °C (54 °F; 285 K) |

| Boiling point | 124 °C (255 °F; 397 K)[1] |

Solubility in water |

soluble 10% vv at 25 Deg. |

| Vapor pressure | 13 hPa at 20 °C[1] |

Magnetic susceptibility (χ) |

-86.2·10−6 cm3/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| N05CC05 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Flammable |

| GHS labelling: | |

Pictograms |

|

Signal word |

Warning |

Hazard statements |

H226 |

Precautionary statements |

P210, P233, P303+P361+P353, P370+P378, P403+P235, P501 |

| Flash point | 24°C - closed cup |

| Explosive limits | Upper limit: 17 %(V) Lower limit: 1.3 %(V) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

Oral - Rat - 1,530 mg/kg Dermal - Rabbit - 14,015 mg/kg |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | [1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

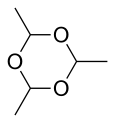

Paraldehyde is the cyclic trimer of acetaldehyde molecules.[2] Formally, it is a derivative of 1,3,5-trioxane, with a methyl group substituted for a hydrogen atom at each carbon. The corresponding tetramer is metaldehyde. A colourless liquid, it is sparingly soluble in water and highly soluble in ethanol. Paraldehyde slowly oxidizes in air, turning brown and producing an odour of acetic acid. It quickly reacts with most plastics and rubber.

Paraldehyde was first observed in 1835 by the German chemist Justus Liebig; its empirical formula was determined in 1838 by Liebig's student Hermann Fehling.[3][4] Paraldehyde was first synthesized in 1848 by the German chemist Valentin Hermann Weidenbusch (1821–1893), another student of Liebig; he obtained paraldehyde by treating acetaldehyde with acid (either sulfuric or nitric acid).[5][6] It has uses in industry and medicine.

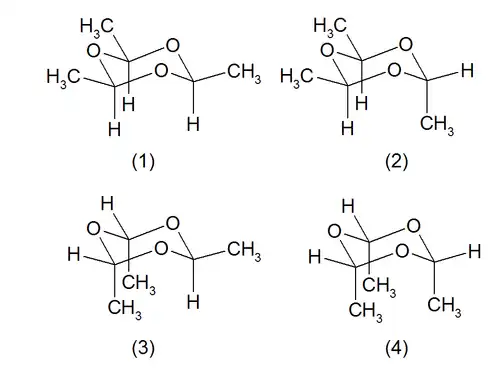

Stereochemistry

Paraldehyde is produced and used as a mixture of two diastereomers, known as cis- and trans-paraldehyde. For each diastereomer, two chair conformers are possible. The structures (1), (4) and (2), (3) are conformers of cis- and trans-paraldehyde, respectively. The structures (3) (a conformer of (2)) and (4) (a conformer of (1)) are high energy conformers on steric grounds (1,3-diaxial interactions are present) and do not exist to any appreciable extent in a sample of paraldehyde.[7][8]

Reactions

Heated with catalytic amounts of acid, it depolymerizes back to acetaldehyde:[9][10]

- C6H12O3 → 3CH3CHO

Since paraldehyde has better handling characteristics, it may be used indirectly or directly as a synthetic equivalent of anhydrous acetaldehyde (b.p. 20 °C). For example, it is used as-is in the synthesis of bromal (tribromoacetaldehyde):[11]

- C6H12O3 + 9 Br2 → 3 CBr3CHO + 9 HBr

Medical applications

Paraldehyde was introduced into clinical practice in the UK by the Italian physician Vincenzo Cervello (1854–1918) in 1882.[12][13][14]

It is a central nervous system depressant and was soon found to be an effective anticonvulsant, hypnotic and sedative. It was included in some cough medicines as an expectorant (though there is no known mechanism for this function beyond the placebo effect).

Paraldehyde was the last injection given to Edith Alice Morrell in 1950 by the suspected serial killer John Bodkin Adams. He was tried for her murder but acquitted.

As a hypnotic/sedative

It was commonly used to induce sleep in sufferers from delirium tremens but has been replaced by other drugs in this regard. It is one of the safest hypnotics and was regularly given at bedtime in psychiatric hospitals and geriatric wards up to the 1970s. Up to 30% of the dose is excreted via the lungs (the rest via the liver). This contributes to a strong unpleasant odour on the breath.

As anti-seizure

It has been used in the treatment of convulsions.[15]

Today, paraldehyde is sometimes used to treat status epilepticus. Unlike diazepam and other benzodiazepines, it does not suppress breathing at therapeutic doses and so is safer when no resuscitation facilities exist or when the patient's breathing is already compromised.[16] This makes it a useful emergency medication for parents and other caretakers of children with epilepsy. Since the dose margin between the anticonvulsant and hypnotic effect is small, paraldehyde treatment usually results in sleep.

Administration

Generic paraldehyde is available in 5 mL sealed glass ampoules. Production in the US has been discontinued, but it was previously marketed as Paral.

Paraldehyde has been given orally, rectally, intravenously and by intramuscular injection. It reacts with rubber and plastic which limits the time it may safely be kept in contact with some syringes or tubing before administration.

- Injection. Intramuscular injection can be very painful and lead to sterile abscesses, nerve damage, and tissue necrosis. Intravenous administration can lead to pulmonary edema, circulatory collapse and other complications.

- Oral. Paraldehyde has a hot burning taste and can upset the stomach. It is often mixed with milk or fruit juice in a glass cup and stirred with a metal spoon.

- Rectal. It may be mixed 1 part paraldehyde with 9 parts saline or, alternatively, with an equal mixture of peanut or olive oil.

Industrial applications

Paraldehyde is used in resin manufacture as an alternative to formaldehyde when making phenol formaldehyde resins. It has also found use as antimicrobial preservative, and rarely as a solvent. It has been used in the generation of aldehyde fuchsin.[17]

References

- 1 2 3 Sigma-Aldrich Co., Paraldehyde.

- ↑ Wankhede, N N; Wankhede, D S; Lande, M K; Arbad, B R (March 2006). "Densities and ultrasonic velocities of binary mixtures of 2,4,6-trimethyl-1,3,5-trioxane + n-alcohols at 298.15, 303.15 and 308.15 K" (PDF). Indian Journal of Chemical Technology. 13 (2): 149–155.

- ↑ Liebig, Justus (1835) "Ueber die Producte der Oxydation des Alkohols" (On the products of the oxidation of ethanol), Annalen der Chemie, 14 : 133–167; see especially p. 141.

- ↑ Fehling, H. (1838) "Ueber zwei dem Aldehyd isomere Verbindungen" (On two compounds that are isomeric to acetaldehyde), Annalen der Chemie, 27 : 319–322; see pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Weidenbusch, H. (1848) "Ueber einige Producte der Einwirkung von Alkalien und Säuren auf den Aldehyd" (On some products of the reaction of alkalies and acids with acetaldehyde), Annalen der Chemie, 66 : 152-165; see pp. 155–158.

- ↑ Paraldehyde was first synthesized by Weidenbusch in 1848:

- (Editorial staff) (April 15, 1885) "The action of paraldehyde," The Therapeutic Gazette, 9 : 247-250; see p. 247.

- See also: Henry Watts, Matthew Moncrieff Pattison Muir, and Henry Forster Morley, Watts' Dictionary of Chemistry, rev'd, vol. 1 (London, England: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1905), p. 106.

- Neill Busse, Der Meister und seine Schüler: Das Netzwerk Justus Liebigs und seiner Studenten [The Master and His Disciples: The network of Justus Liebig and his students] (Hildesheim, Germany: Georg Olms Verlag, 2015); for Weidenbusch's dates, see p. 274.

- See also: Joseph S. Fruton (March 1988) "The Liebig research group: A reappraisal," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 132 (1) : 1–66; see p. 59.

- See also: Deutsche Biographische Enzyklopädie Archived 2014-08-11 at the Wayback Machine (German Biographical Encyclopedia), p. 1154.

- ↑ Kewley, R. (1970). "Microwave spectrum of paraldehyde". Canadian Journal of Chemistry. 48 (5): 852–855. doi:10.1139/v70-136.

- ↑ Carpenter, D. C.; Brockway, L. O. (1936). "The Electron Diffraction Study of Paraldehyde". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 58 (7): 1270–1273. doi:10.1021/ja01298a053.

- ↑ Kendall, E. C.; McKenzie, B. F. (1941). "dl-Alanine". Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, vol. 1, p. 21

- ↑ Nathan L. Drake & Giles B. Cooke (1943). "Methyl isopropyl carbinol". Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, vol. 2, p. 406

- ↑ F. A. Long & J. W. Howard. "Bromal". Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, vol. 2, p. 87

- ↑ López-Muñoz F, Ucha-Udabe R, Alamo C (December 2005). "The history of barbiturates a century after their clinical introduction". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 1 (4): 329–43. PMC 2424120. PMID 18568113.

- ↑ See:

- Cervello, Vincenzo (1883) "Sull'azione fisiologica della paraldeide e contributo allo studio del cloralio idrato" (On the physiological action of paraldehyde and contribution to the study of chloral hydrate), Archivio per le Scienze Mediche, 6 (12) : 177–214.

- Cervello, Vincenzo (1884) "Recherches cliniques et physiologiques sur la paraldehyde" (Clinical and physiological investigations into paraldehyde), Archives italiennes de biologie, 6 : 113–134.

- ↑ For biographical information about Vencenzo Cervello, see: Dizionario Biografico (in Italian)

- ↑ Townend W, Mackway-Jones K (January 2002). "Towards evidence based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. Phenytoin or paraldehyde as the second drug for convulsions in children". Emergency Medicine Journal. 19 (1): 50. doi:10.1136/emj.19.1.50. PMC 1725762. PMID 11777879.

- ↑ Norris E, Marzouk O, Nunn A, McIntyre J, Choonara I (1999). "Respiratory depression in children receiving diazepam for acute seizures: a prospective study". Dev Med Child Neurol. 41 (5): 340–3. doi:10.1017/S0012162299000742. PMID 10378761.

- ↑ Nettleton GS (February 1982). "The role of paraldehyde in the rapid preparation of aldehyde fuchsin". Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 30 (2): 175–8. doi:10.1177/30.2.6174561. PMID 6174561.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paraldehyde. |