Solifenacin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vesicare, Vesicare LS |

| Other names | YM905 |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 5 mg[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605019 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 90% |

| Protein binding | 98% |

| Metabolism | CYP3A4 |

| Metabolites | Glucuronide, N-oxide, others |

| Elimination half-life | 45 to 68 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney (69.2%) and fecal (22.5%) |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H26N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 362.473 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Solifenacin, sold as the brand name Vesicare among others, is a medicine used to treat overactive bladder and neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO).[2][3] It may help with incontinence, urinary frequency, and urinary urgency.[4] Benefits appear similar to other medications in the class.[5] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include dry mouth, constipation, and urinary tract infection.[2][3] Severe side effects may include urinary retention, QT prolongation, hallucinations, glaucoma, and anaphylaxis.[2][4][3] It is unclear if use is safe during pregnancy.[2] It is of the antimuscarinic class and works by decreasing bladder contractions.[2]

Solifenacin was approved for medical use in the United States in 2004.[2][3][6] A month's supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £28 as of 2019.[4] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$370.[7] In 2017, it was the 283rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[8][9]

Medical use

It is used to treat overactive bladder.[2] It may help with incontinence, urinary frequency, and urinary urgency.[4]

Benefits appear similar to other antimuscarinics such as oxybutynin, tolterodine, and darifenacin.[5]

It is also used to treat neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO), a form of bladder dysfunction related to neurological impairment, in children ages two years and older.[3] NDO is a dysfunction of the bladder that results from disease or injury in the nervous system.[3] NDO may be related to congenital conditions (often-inherited conditions beginning at or before birth), such as spina bifida (myelomeningocele), or other conditions such as spinal cord injury.[3] With NDO, there is overactivity of the bladder wall muscle, which normally relaxes to allow storage of urine.[3] The bladder wall muscle overactivity results in sporadic bladder muscle contraction, which increases pressure in the bladder and decreases the volume of urine the bladder can hold.[3] If NDO is not treated, increased pressure in the bladder can put the upper urinary tract at risk of harm, including possible permanent damage to the kidneys.[3] In addition, spontaneous bladder muscle contractions can lead to unexpected and frequent leakage of urine with symptoms of urinary urgency (immediate urge to urinate), frequency (urinating more often than normal) and incontinence (loss of bladder control).[3]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 5 mg by mouth.[1]

Contraindications

Solifenacin is contraindicated for people with urinary retention, gastric retention, uncontrolled or poorly controlled closed-angle glaucoma, severe liver disease (Child-Pugh class C),[10] and hemodialysis.[11]

Long QT syndrome is not a contraindication although solifenacin, like tolterodine and darifenacin, binds to hERG channels of the heart and may prolong the QT interval. This mechanism appears to be seldom clinically relevant.[12]

Solifenacin is not to be used in people with gastric retention (reduced emptying of the stomach), uncontrolled narrow angle glaucoma (fluid buildup in the eye which raises eye pressure) or hypersensitivity (allergic reaction) to solifenacin or any of its components.[3] Solifenacin is also not recommended for use in people with severe liver failure, significant bladder outlet obstruction in the absence of clean intermittent catheterization, decreased gastrointestinal motility (slowed intestinal contractions), or at high risk of QT prolongation (an electrical disturbance where the heart muscle takes longer than normal to recharge between beats), including people with a known history of QT prolongation and people taking medications known to prolong the QT interval.[3]

Side effects

The most common side effects of solifenacin are dry mouth, constipation and urinary tract infection.[3] As all anticholinergics, solifenacin may rarely cause hyperthermia due to decreased perspiration.[10] Somnolence (sleepiness or drowsiness) has been reported.[3] Severe allergic reactions, such as angioedema (swelling beneath the skin) and anaphylaxis, have been reported in people treated with solifenacin succinate and may be life-threatening.[3]

Interactions

Solifenacin is metabolized in the liver by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A4. When administered concomitantly with drugs that inhibit CYP3A4, such as ketoconazole, the metabolism of solifenacin is impaired, leading to an increase in its concentration in the body and a reduction in its excretion.[10]

As stated above, solifenacin may also prolong the QT interval. Therefore, administering it concomitantly with drugs which also have this effect, such as moxifloxacin or pimozide, can theoretically increase the risk of arrhythmia.[2]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Solifenacin is a competitive cholinergic receptor antagonist, selective for the M3 receptor subtype. The binding of acetylcholine to these receptors, particularly M3, plays a critical role in the contraction of smooth muscle. By preventing the binding of acetylcholine to these receptors, solifenacin reduces smooth muscle tone in the bladder, allowing the bladder to retain larger volumes of urine and reducing the number of micturition, urgency and incontinence episodes. Because of a long elimination half life, a once-a-day dose can offer 24-hour control of the urinary bladder smooth muscle tone.[11]

Pharmacokinetics

Peak plasma concentrations are reached three to eight hours after absorption from the gut. In the bloodstream, 98% of the substance are bound to plasma proteins, mainly acidic ones. Metabolism is mediated by the liver enzyme CYP3A4 and possibly others. There is one known active metabolite, 4R-hydroxysolifenacin, and three inactive ones, the N-glucuronide, the N-oxide and the 4R-hydroxy-N-oxide. The elimination half-life is 45 to 68 hours. 69% of the substance, both in its original form and as metabolites, are excreted renally and 23% via the feces.[11]

Chemistry

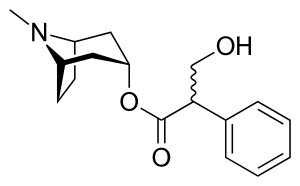

Like other anticholinergics, solifenacin is an ester of a carboxylic acid containing (at least) an aromatic ring with an alcohol containing a nitrogen atom. While in the prototype anticholinergic atropine the bicyclic ring is tropane, solifenacin replaces it with quinuclidine.

The free base is a yellow oil, while the salt solifenacin succinate forms yellowish crystals.[13]

History

The compound was studied using animal models by the Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. of Tokyo, Japan. It was known as YM905 when under study in the early 2000s.[14]

Solifenacin was approved for medical used in the United States in 2004 with an indication to treat overactive bladder in adults 18 years and older.[3][6]

In May 2020, solifenacin was approved for medical use in the United States with an indication to treat neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO), a form of bladder dysfunction related to neurological impairment, in children ages two years and older.[3]

The efficacy of solifenacin to treat neurogenic detrusor overactivity (NDO) was established in two clinical trials with a total of 95 pediatric NDO participants, ages two to 17 years old.[3] The studies were designed to measure (as a primary efficacy endpoint) the maximum amount of urine the bladder could hold after 24 weeks of treatment.[3] In the first study, 17 participants ages two to less than five years old were able to hold an average of 39 mL more urine than when the study began.[3] In the second study, 49 participants ages five to 17 years were able to hold an average of 57 mL more urine than when the study began.[3] Reductions in spontaneous bladder contractions, bladder pressure and number of incontinence episodes were also observed in both studies.[3] The approval of Vesicare LS was granted to Astellas Pharma US, Inc.[3]

Society and culture

The INN is solifenacin.[15] It is manufactured and marketed by Astellas, GlaxoSmithKline[2] and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.[16]

Cost

A 2006 cost-effectiveness study found that 5 mg solifenacin had the lowest cost and highest effectiveness among anticholinergic drugs used to treat overactive bladder in the United States, with an average medical cost per successfully treated patient of $6863 per year.[17] By 2019, with the introduction of generics, the retail cost of a month's supply was down to $20 in the US.

.svg.png.webp) Solifenacin costs (US)

Solifenacin costs (US).svg.png.webp) Solifenacin prescriptions (US)

Solifenacin prescriptions (US)

References

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Solifenacin Succinate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2019-04-02. Retrieved 2019-03-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 "FDA Approves First Treatment for a Form of Bladder Dysfunction in Pediatric Patients as Young as 2 Years of Age". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 4 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 761. ISBN 9780857113382.

- 1 2 "[93] Are claims for newer drugs for overactive bladder warranted?". Therapeutics Initiative. 22 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- 1 2 "Drug Approval Package: VesiCare (Solifenacin Succinate) NDA #021518". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ↑ "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ "Solifenacin Succinate - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 Lexi-Comp (December 2009). "Solifenacin". The Merck Manual Professional. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 Jasek, W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (62nd ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. pp. 8659–62. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Vesicare 5mg & 10mg film-coated tablets". eMC. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ↑ The Merck Index. An Encyclopaedia of Chemicals, Drugs and Biologicals (14 ed.). 2006. p. 1494. ISBN 978-0-911910-00-1.

- ↑ Kobayashi, S.; et al. (July 2001). "Effects of YM905, a Novel Muscarinic M3-Receptor Antagonist, on Experimental Models of Bowel Dysfunction In Vivo". Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 86 (3): 281–288. PMID 11488427. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2015-07-17.

- ↑ "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN). Recommended International Nonproprietary Names: List 47" (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 106. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Teva Introduces Generic of Vesicare to Treat Overactive Bladder". Bloomberg Law. 22 April 2019. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019.

- ↑ Ko Y, Malone DC, Armstrong EP (Dec 2006). "Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of antimuscarinic agents for the treatment of overactive bladder". Pharmacotherapy. 26 (12): 1694–702. doi:10.1592/phco.26.12.1694. PMID 17125433. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2015-07-17.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

- "Solifenacin succinate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-10-22. Retrieved 2020-05-26.