17q12 microdeletion syndrome

| 17q12 microdeletion syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: 17q12 deletion syndrome | |

| |

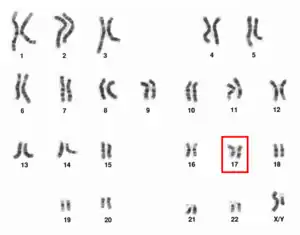

| The human karyotype with chromosome 17 highlighted | |

| Symptoms | Kidney problems, diabetes, reproductive anomalies, neuroatypicality |

| Usual onset | Conception |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Chromosome microdeletion |

| Diagnostic method | Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

17q12 microdeletion syndrome, also known as 17q12 deletion syndrome, is a rare chromosomal anomaly caused by the deletion of a small amount of material from a region in the long arm of chromosome 17. It is typified by deletion of the HNF1B gene, resulting in kidney abnormalities and renal cysts and diabetes syndrome. It also has neurocognitive effects, and has been implicated as a genetic factor for autism and schizophrenia.

17q12 microdeletion syndrome is not to be confused with 17q12 microduplication syndrome, caused by the addition of genetic material in the same region from which it is removed in the microdeletion, or 17q21.31 microdeletion syndrome, another name for Koolen–De Vries syndrome.

Signs and symptoms

17q12 microdeletions have a variable phenotype, ranging from few or no symptoms to severe disability. The condition is thought to be underdiagnosed, and cases with milder phenotypes may not reach clinical attention unless they have an affected child themselves.[1][2] The most characteristic symptom is renal cysts and diabetes syndrome (RCAD), also known as "type 5 diabetes", which is caused by deletion of the associated HNF1B gene in the region.[3] RCAD is associated with kidney abnormalities and a characteristic form of diabetes that causes atrophy of the pancreas. However, some people with 17q12 microdeletions have normal renal function.[2] RCAD is diagnosed in approximately 40% of people with 17q12 microdeletions, usually prior to age 25, while kidney abnormalities more broadly occur in approximately 85-90%.[4]

People with 17q12 microdeletions have a characteristic facial phenotype, albeit a subtle one not usually obvious in daily life. Macrocephaly is common, along with high arched eyebrows, flattening of the malar region, and epicanthic folds.[4] Pathological short stature is possible, and a characteristic "short and stocky" body shape occurs in many cases.[1]

17q12 microdeletions are associated with neurocognitive and developmental involvement of variable severity. Some have mild to moderate intellectual disability; however, such impairment is not universal.[5][6] Average intelligence is in the average to low average range.[7] Speech delay is common, regardless of intellectual functioning. The most striking association between 17q12 microdeletions and neurodevelopment is the raised prevalence of autism spectrum disorder, with significant increases in both diagnosis and subclinical autistic traits.[7][8] 17q12 microdeletions have been implicated as one of the major genetic causes of high-functioning autistic spectrum disorders.[1] Schizophrenia is also a significant psychiatric complication of 17q12 microdeletion syndrome. 17q12 microdeletions are estimated to occur in approximately 1 in 1,600 schizophrenic people, compared to an estimation of below 1 in 50,000 in the general population.[8] Epilepsy, usually mild, occurs in approximately one-third of cases.[6]

Reproductive system anomalies are associated with 17q12 microdeletions, particularly in females. 17q12 microdeletions have been linked to uterine malformations, most frequently Müllerian agenesis, where the uterus and part of the vaginal canal are absent.[4][9]

Causes

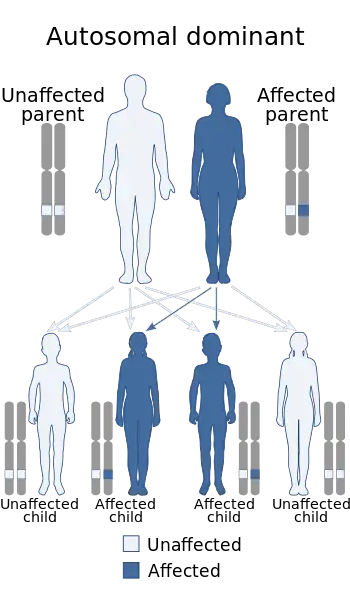

17q12 microdeletion syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder, where one copy of the relevant mutation is enough to cause the condition. Most cases are de novo, or spontaneous mutations that do not occur in the proband's parents;[10] approximately 75% are de novo, while 25% are inherited.[4] People with 17q12 microdeletions who have normal fertility have a 50% chance of passing the deletion down to their offspring.[1] Environmental factors have not been implicated in the syndrome.[1]

Diagnosis

Like other chromosomal microdeletions, 17q12 microdeletion syndrome is diagnosed via fluorescence in situ hybridization.[11] Traditional karyotyping, used to diagnose major chromosomal disorders such as aneuploidy, is rarely sensitive enough to detect microdeletions.[11]

Treatment

As the underlying 17q12 microdeletion is an innate genetic disorder, it cannot by itself be treated. Rather, treatment is symptomatic and supportive. The high prevalence of kidney disease indicates routine monitoring of renal function, particularly in people taking potentially nephrotoxic medications such as lithium. The comorbities involved in 17q12 microdeletion syndrome require caution in medical treatment; for instance, the increased risk of diabetes requires strict monitoring for post-transplantation diabetes mellitus in kidney transplant patients, as does the risk of weight gain and diabetes from neuroleptic drugs in those with a mental health diagnosis.[4]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of 17q12 microdeletion syndrome is unknown, and it is likely to be underdiagnosed. 17q12 microdeletions are estimated to occur in approximately 1 in 600 people on the autism spectrum and 1 in 1,600 with schizophrenia, but are far rarer in the general population.[8] General prevalence is estimated to be between 1 in 14,000[4] and 1 in 62,500.[12]

In addition to the increased prevalence in autism and schizophrenia, some other clinical populations have increased prevalence of 17q12 microdeletion syndrome. The condition occurs in approximately 2% of those with congenital kidney abnormalities and 3-6% of women with Müllerian agenesis.[4] It is one of the ten most common microdeletions amongst children with idiopathic developmental delay.[1]

Microduplication

17q12 microduplication syndrome is far rarer than the corresponding microdeletion, estimated to occur roughly one-fifth as frequently as 17q12 microdeletion syndrome. Due to its rarity and the overlap between their phenotypes, 17q12 microduplications are usually discussed as an adjunct to microdeletions.[3] Like the microdeletion syndrome, the microduplication syndrome has a broad phenotypic range, ranging from asymptomatic to profound disability; intellectual disability is frequently but not always more severe than the microdeletion, while physical health is often better.[13][14] Epilepsy is a frequent finding. A case of sex reversal has been reported.[13] While autism comorbid with 17q12 microduplication has been reported, it appears far rarer than in the microdeletion.[15] Physical anomalies associated with 17q12 microduplication syndrome include syndactyly, microcephaly, epicanthic folds, and thick eyebrows or a unibrow.[13][14] The 17q12 microduplication appears to have a low penetrance, as many cases are inherited from asymptomatic parents.[13]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Unique, Moreno de Luca D, Hultén M (2018). "17q12 microdeletions" (PDF). Unique. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-29. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- 1 2 George AM, Love DR, Hayes I, Tsang B (2012). "Recurrent Transmission of a 17q12 Microdeletion and a Variable Clinical Spectrum". Molecular Syndromology. 2 (2): 72–75. doi:10.1159/000335344. PMC 3326281. PMID 22511894.

- 1 2 Wan S, Zheng Y, Dang Y, Song T, Chen B, Zhang J (17 May 2019). "Prenatal diagnosis of 17q12 microdeletion and microduplication syndrome in fetuses with congenital renal abnormalities". Molecular Cytogenetics. 12 (19): 19. doi:10.1186/s13039-019-0431-7. PMC 6525371. PMID 31131025.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mitchel MW, Moreno de Luca D, Myers SM, Levy RV, Turner S, Ledbetter DH, Martin CL (15 October 2020). "17q12 Recurrent Deletion Syndrome". NCBI GeneReviews. PMID 27929632. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ↑ Nagamani SCS, Erez A, Shen J, Li C, Roeder E, Cox S, Karavati L, Pearson M, Kang SHL, Sahoo T, Lalani SR, Stankiewicz P, Sutton VR, Cheung SW (2010). "Clinical spectrum associated with recurrent genomic rearrangements in chromosome 17q12". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (1): 278–284. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.174. PMC 2987224. PMID 19844256.

- 1 2 Mefford HC, Clauin S, Sharp AJ, Moller RS, Ullmann R, Kapur R, Pinkel D, Cooper GM, Ventura M, Ropers HH, Tommerup N, Eichler EE, Bellanne-Chantelot C (November 2007). "Recurrent Reciprocal Genomic Rearrangements of 17q12 Are Associated with Renal Disease, Diabetes, and Epilepsy". American Journal of Human Genetics. 81 (5): 1057–1069. doi:10.1086/522591. PMC 2265663. PMID 17924346.

- 1 2 Clissod RL, Shaw-Smith C, Turnpenny P, Bunce B, Bockenhauer D, Kerecuk L, Bingham C (July 2016). "Chromosome 17q12 microdeletions but not intragenic HNF1B mutations link developmental kidney disease and psychiatric disorder". Kidney International. 90 (1): 203–211. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.03.027. PMC 4915913. PMID 27234567.

- 1 2 3 Moreno de Luca D, Mulle JG, Kaminsky EB, Sanders SJ (7 January 2011). "Deletion 17q12 Is a Recurrent Copy Number Variant that Confers High Risk of Autism and Schizophrenia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 87 (5): 618–630. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.004. PMC 2978962. PMID 21055719.

- ↑ Bernardini L, Gimelli S, Gervasini C, Carella M, Baban A, Frontino G, Barbano G, Diviza MT, Fedele L, Novelli A, Béna F, Lalatta F, Miozzo M, Dallapicolla B (4 November 2009). "Recurrent microdeletion at 17q12 as a cause of Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome: two case reports". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 4 (25): 25. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-4-25. PMC 2777856. PMID 19889212.

- ↑ Genetics Home Reference. "What is a gene mutation and how do mutations occur?". Medline Plus. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- 1 2 Shaffer LG (15 May 2001). "Diagnosis of Microdeletion Syndromes by Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH)". Current Protocols in Human Genetics. 14 (1): Unit 8.10. doi:10.1002/0471142905.hg0810s14. PMID 18428311. S2CID 20989937.

- ↑ Roehlen N, Hilger H, Stock F, Gläser B, Guhl J, Schmitt-Graeff A, Seufert J, Laubner K (October 2018). "17q12 Deletion Syndrome as a Rare Cause for Diabetes Mellitus Type MODY5". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 103 (10): 3601–3610. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00955. PMID 30032214. Archived from the original on 2020-12-18. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- 1 2 3 4 Bierhals T, Maddukuri SB, Kutsche K, Girisha KM (February 2013). "Expanding the phenotype associated with 17q12 duplication: Case report and review of the literature". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 161 (2): 352–359. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.35730. PMID 23307502. S2CID 12242509. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- 1 2 Unique, Girisha KM (2018). "17q12 microduplications" (PDF). Unique. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-26. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ↑ Brandt T, Desai K, Grodberg D, Mehta L, Cohen N, Tryfon A, Kolevzon A, Soorya L, Buxbaum JD, Edelmann L (May 2012). "Complex autism spectrum disorder in a patient with a 17q12 microduplication". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 158A (5): 1170–1177. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.35267. PMID 22488896. S2CID 20832319.

External links

| Classification |

|---|