Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder

| Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Frozen shoulder | |

| |

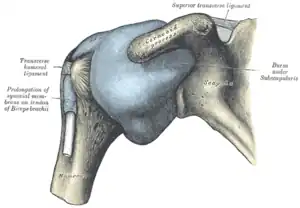

| The right shoulder & glenohumeral joint. | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Shoulder pain, stiffness[1] |

| Complications | Fracture of the humerus, biceps tendon rupture[2] |

| Usual onset | 40 to 60 year old[1] |

| Duration | May last years[1] |

| Types | Primary, secondary[2] |

| Causes | Often unknown, prior shoulder injury[1][2] |

| Risk factors | Diabetes, hypothyroidism[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pinched nerve, autoimmune disease, biceps tendinopathy, osteoarthritis, rotator cuff tear, cancer, bursitis[1] |

| Treatment | NSAIDs, physical therapy, steroids, injecting the shoulder at high pressure, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | ~4%[1] |

Adhesive capsulitis, also known as frozen shoulder, is a condition associated with shoulder pain and stiffness.[1] There is a loss of the ability to move the shoulder, both voluntarily and by others, in multiple directions.[1][2] The shoulder itself; however, does not generally hurt significantly when touched.[1] Muscle loss around the shoulder may also occur.[1] Onset is gradual over weeks to months.[2] Complications can include fracture of the humerus or biceps tendon rupture.[2]

The cause in most cases is unknown.[1] The condition can also occur after injury or surgery to the shoulder.[2] Risk factors include diabetes and thyroid disease.[1] The underlying mechanism involves Inflammation and scarring.[2][3] The diagnosis is generally based on a person's symptoms and a physical exam.[1] The diagnosis may be supported by an MRI.[1]

The condition often resolves over time without intervention but this may take several years.[1] While a number of treatments such as NSAIDs, physical therapy, steroids, and injecting the shoulder at high pressure may be tried it is unclear what is best.[1] Surgery may be suggested for those who do not get better after a few months.[1] About 4% of people are affected.[1] It is more common in people 40–60 years of age and in women.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include shoulder pain and limited range of motion although these symptoms are common in many shoulder conditions. An important symptom of adhesive capsulitis is the severity of stiffness that often makes it nearly impossible to carry out simple arm movements. Pain due to frozen shoulder is usually dull or aching and may be worse at night and with any motion.

The symptoms of primary frozen shoulder has been described as having three[4] or four stages.[5] Sometimes a prodromal stage is described that can be present up to three months prior to the shoulder freezing. During this stage people describe sharp pain at end ranges of motion, achy pain at rest, and sleep disturbances.

- Stage one: The "freezing" or painful stage, which may last from six weeks to nine months, and in which the patient has a slow onset of pain. As the pain worsens, the shoulder loses motion.[6]

- Stage two: The "frozen" or adhesive stage is marked by a slow improvement in pain but the stiffness remains. This stage generally lasts from four to nine months.

- Stage three: The "thawing" or recovery, when shoulder motion slowly returns toward normal. This generally lasts from 5 to 26 months.[7]

Physical exam findings include restricted range of motion in all planes of movement in both active and passive range of motion.[8] This contrasts with conditions such as shoulder impingement syndrome or rotator cuff tendinitis in which the active range of motion is restricted but passive range of motion is normal. Some exam maneuvers of the shoulder may be impossible due to pain.

Causes

The causes of adhesive capsulitis are incompletely understood, however there are several factors associated with higher risk. Risk factors for secondary adhesive capsulitis include injury or surgery that lead to prolonged immobility. Risk factors for primary, or idiopathic adhesive capsulitis include many systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, stroke, lung disease, connective tissue diseases, thyroid disease, heart disease, autoimmune disease, and Dupuytren's contracture.[9] Both type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes are risk factors for the condition.[9]

Primary

Primary adhesive capsulitis, also known as idiopathic adhesive capsulitis occurs with no known trigger. It is more likely to develop in the non-dominant arm.

Secondary

Secondary adhesive capsulitis develops after an injury or surgery to the shoulder.

Pathophysiology

The underlying pathophysiology is incompletely understood but is generally accepted to have both inflammatory and fibrotic components. The hardening of the shoulder joint capsule is central to the disease process. This is the result of scar tissue (adhesions) around the joint capsule.[9] There also may be reduction in synovial fluid, which normally helps the shoulder joint, a ball and socket joint, move by lubricating the gap between the humerus (upper arm bone) and the socket in the shoulder blade. In the painful stage (stage I), there is evidence of inflammatory cytokines in the joint fluid. Later stages are characterized by dense collagenous tissue in the joint capsule.[9]

Under the microscope the appearance of shoulder joint capsule is very similar to the tissue which stops the fingers from moving in Dupuytren’s contracture, a fairly common condition where the little finger curls into the palm.

Diagnosis

Adhesive capsulitis can be diagnosed by history and physical exam. It is often a diagnosis of exclusion as other causes of shoulder pain and stiffness must first be ruled out. On physical exam, adhesive capsulitis can be diagnosed if limits of the active range of motion are the same or similar to the limits to the passive range of motion. The movement that is most severely inhibited is external rotation of the shoulder.

Imaging studies are not required for diagnosis but may be used to rule out other causes of pain. Radiographs are often normal but imaging features of adhesive capsulitis can be seen on ultrasound or non-contrast MRI. Ultrasound and MRI can help in diagnosis by assessing the coracohumeral ligament, with a width of greater than 3 mm being 60% sensitive and 95% specific for the diagnosis. Shoulders with adhesive capsulitis also characteristically fibrose and thicken at the axillary pouch and rotator interval, best seen as dark signal on T1 sequences with edema and inflammation on T2 sequences.[10] A finding on ultrasound associated with adhesive capsulitis is hypoechoic material surrounding the long head of the biceps tendon at the rotator interval, reflecting fibrosis. In the painful stage, such hypoechoic material may demonstrate increased vascularity with Doppler ultrasound.[11]

Management

Management of this disorder focuses on restoring joint movement and reducing shoulder pain, involving medications, physical therapy, or surgery. Treatment may continue for months; there is no strong evidence to favor any particular approach.[12]

Medications such as NSAIDs can be used for pain control. Corticosteroids are used in some cases either through local injection or systemically. Oral steroids may provide short-term benefits in range of movement and pain but have side effects such as hyperglycemia.[13] Steroid injections compared to physical therapy have similar effect in improving shoulder function and decreasing pain.[14] The benefits of steroid injections appear to be short-term.[15][16] It is unclear whether ultrasound guided injections can improve pain or function over anatomy-guided injections.[17]

The role for physical therapy in adhesive capsulitis is not settled. Physical therapy is utilized as an initial treatment in adhesive capsulitis or frozen shoulder with the use of range of motion (ROM) exercises and manual therapy techniques of shoulder joint to restore range and function. A low-dose corticosteroid injection and home exercise programs in those with symptoms less than 6 months may be useful. There may be some benefit with manual therapy and stretching as part of a rehabilitation program but due to the time required such use should be carefully considered.[18] Physical therapists may utilize joint mobilizations directly at the glenohumeral joint to decrease pain, increase function, and increase range of motion as another form of treatment.[5] There are some studies that have shown that intensive passive stretching can promote healing.[19] Additional interventions include modalities such as ultrasound, shortwave diathermy, laser therapy and electrical stimulation.[5][20] Another osteopathic technique used to treat the shoulder is called the Spencer technique. Mobilization techniques and other therapeutic modalities are most commonly used by physical therapist, however there is not strong evidence that these methods can change the course of the disease.[19]

If these measures are unsuccessful, more aggressive interventions such as surgery can be trialed. Manipulation of the shoulder under general anesthesia to break up the adhesions is sometimes used.[12] Hydrodilatation or distension arthrography is controversial.[21] However, some studies show that arthrographic distension may play a positive role in reducing pain and improve range of movement and function.[22] Surgery to cut the adhesions (capsular release) may be indicated in prolonged and severe cases; the procedure is usually performed by arthroscopy.[23] Surgical evaluation of other problems with the shoulder, e.g., subacromial bursitis or rotator cuff tear may be needed. Resistant adhesive capsulitis may respond to open release surgery. This technique allows the surgeon to find and correct the underlying cause of restricted glenohumeral movement such as contracture of coracohumeral ligament and rotator interval.[24] Physical therapy may achieve improved results after surgical procedure and postoperative rehabilitation.[25]

Prognosis

Most cases of adhesive capsulitis are self limiting but may take 1–3 years to fully resolve. Pain and stiffness may not completely resolve in 20-50% of people.[9]

Epidemiology

Adhesive capsulitis newly affects approximately 0.75% to 5.0% percent of people a year.[26] Rates are higher in people with diabetes (10–46%).[27] Following breast surgery, some known complications include loss of shoulder range of motion (ROM) and reduced functional mobility in the involved arm.[28] Occurrence is rare in children and people under 40 with highest prevalence between 40 and 70 years of age.[12] The condition is more common in women than in men (70% of patients are women aged 40–60). People with diabetes, stroke, lung disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or heart disease are at a higher risk for frozen shoulder. Symptoms in people with diabetes may be more protracted than in the non-diabetic population.[29]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Ramirez, J (1 March 2019). "Adhesive Capsulitis: Diagnosis and Management". American Family Physician. 99 (5): 297–300. PMID 30811157.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 St Angelo, JM; Fabiano, SE (January 2020). "Adhesive Capsulitis". PMID 30422550.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Redler, LH; Dennis, ER (15 June 2019). "Treatment of Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 27 (12): e544–e554. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00606. PMID 30632986.

- ↑ "Your Orthopaedic Connection: Frozen Shoulder". Archived from the original on 2017-10-20. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- 1 2 3 Kelley MJ, Shaffer MA, Kuhn JE, Michener LA, Seitz AL, Uhl TL, et al. (May 2013). "Shoulder pain and mobility deficits: adhesive capsulitis". The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 43 (5): A1-31. doi:10.2519/jospt.2013.0302. PMID 23636125.

- ↑ Burnham, Jeremy. "Frozen Shoulder Diagnosis & Management". Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ↑ "Reduce Frozen Shoulder Recovery Time". 2016-06-24. Archived from the original on 2019-04-11. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ↑ Jayson MI (October 1981). "Frozen shoulder: adhesive capsulitis". British Medical Journal. 283 (6298): 1005–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.283.6298.1005. JSTOR 29503905. PMC 1495653. PMID 6794738.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Le, Hai V.; Lee, Stella J.; Nazarian, Ara; Rodriguez, Edward K. (2017). "Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: review of pathophysiology and current clinical treatments". Shoulder & Elbow. 9 (2): 75–84. doi:10.1177/1758573216676786. ISSN 1758-5732. PMC 5384535. PMID 28405218.

- ↑ Shaikh A, Sundaram M (January 2009). "Adhesive capsulitis demonstrated on magnetic resonance imaging". Orthopedics. 32 (1): 2–62. doi:10.3928/01477447-20090101-20. PMID 19226048.

- ↑ Arend CF. Ultrasound of the Shoulder. Master Medical Books, 2013. Chapter on ultrasound findings of adhesive capsulitis available at ShoulderUS.com Archived 2018-12-16 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 Ewald A (February 2011). "Adhesive capsulitis: a review". American Family Physician. 83 (4): 417–22. PMID 21322517.

- ↑ Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM, Johnston RV (October 2006). "Oral steroids for adhesive capsulitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006189. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006189. PMID 17054278.

- ↑ Sun Y, Lu S, Zhang P, Wang Z, Chen J (May 2016). "Steroid Injection Versus Physiotherapy for Patients With Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder: A PRIMSA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Medicine. 95 (20): e3469. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000003469. PMC 4902394. PMID 27196452.

- ↑ Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM (2003-01-20). "Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004016. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004016. PMC 6464922. PMID 12535501.

- ↑ Kitridis, D; Tsikopoulos, K; Bisbinas, I; Papaioannidou, P; Givissis, P (December 2019). "Efficacy of Pharmacological Therapies for Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 47 (14): 3552–3560. doi:10.1177/0363546518823337. PMID 30735431.

- ↑ Bloom JE, Rischin A, Johnston RV, Buchbinder R (August 2012). "Image-guided versus blind glucocorticoid injection for shoulder pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD009147. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009147.pub2. PMID 22895984.

- ↑ Minns Lowe, C; Barrett, E; McCreesh, K; de Búrca, N; Lewis, J (2019). "Clinical effectiveness of non-surgical interventions for primary frozen shoulder: A systematic review". Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 51 (8): 539–556. doi:10.2340/16501977-2578. ISSN 1650-1977. PMID 31233183.

- 1 2 Noten, Suzie; Meeus, Mira; Stassijns, Gaetane; Glabbeek, Francis Van; Verborgt, Olivier; Struyf, Filip (2016-05-01). "Efficacy of Different Types of Mobilization Techniques in Patients With Primary Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder: A Systematic Review". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 97 (5): 815–825. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.07.025. hdl:10067/1328760151162165141. ISSN 0003-9993. PMID 26284892. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ↑ Green S, Buchbinder R, Hetrick S (2003-04-22). "Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD004258. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004258. PMID 12804509.

- ↑ Tveitå EK, Tariq R, Sesseng S, Juel NG, Bautz-Holter E (April 2008). "Hydrodilatation, corticosteroids and adhesive capsulitis: a randomized controlled trial". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 9: 53. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-9-53. PMC 2374785. PMID 18423042.

- ↑ Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM, Johnston RV, Cumpston M (January 2008). "Arthrographic distension for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD007005. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007005. PMID 18254123.

- ↑ Baums MH, Spahn G, Nozaki M, Steckel H, Schultz W, Klinger HM (May 2007). "Functional outcome and general health status in patients after arthroscopic release in adhesive capsulitis". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 15 (5): 638–44. doi:10.1007/s00167-006-0203-x. PMID 17031613.

- ↑ D'Orsi GM, Via AG, Frizziero A, Oliva F (April 2012). "Treatment of adhesive capsulitis: a review". Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2 (2): 70–8. PMC 3666515. PMID 23738277.

- ↑ Cho CH, Bae KC, Kim DH (September 2019). "Treatment Strategy for Frozen Shoulder". Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery. 11 (3): 249–257. doi:10.4055/cios.2019.11.3.249. PMC 6695331. PMID 31475043.

- ↑ Bunker, Tim (2009). "Time for a new name for frozen shoulder—contracture of the shoulder". Shoulder&Elbow. 1: 4–9. doi:10.1111/j.1758-5740.2009.00007.x.

- ↑ Minns Lowe, C; Barrett, E; McCreesh, K; de Búrca, N; Lewis, J (2019). "Clinical effectiveness of non-surgical interventions for primary frozen shoulder: A systematic review". Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 51 (8): 539–556. doi:10.2340/16501977-2578. ISSN 1650-1977. PMID 31233183.

- ↑ Yang, Ajax; Sokolof, Jonas; Gulati, Amitabh (September 2018). "The effect of preoperative exercise on upper extremity recovery following breast cancer surgery: a systematic review". International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. Internationale Zeitschrift Fur Rehabilitationsforschung. Revue Internationale de Recherches de Readaptation. 41 (3): 189–196. doi:10.1097/MRR.0000000000000288. ISSN 1473-5660. PMID 29683834.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers about Shoulder Problems". Archived from the original on 2017-07-28. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |