Beck's triad (cardiology)

| Beck's triad (cardiology) | |

|---|---|

| Other names: acute tamponade triad | |

| |

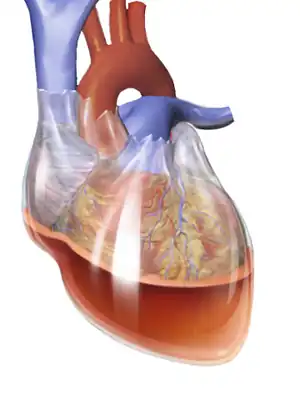

| Hemopericardium, a possible cause of cardiac tamponade | |

| Differential diagnosis | cardiac tamponade |

Beck's triad is a collection of three medical signs associated with acute cardiac tamponade,[1] a medical emergency when excessive fluid accumulates in the pericardial sac around the heart and impairs its ability to pump blood.

The signs are low arterial blood pressure, distended neck veins, and distant, muffled heart sounds.[1]

Narrowed pulse pressure might also be observed. The concept was developed in 1935 by Claude Beck, a resident and later Professor of Cardiovascular Surgery at Case Western Reserve University.[2][3]

Components

The signs are low arterial blood pressure, distended neck veins, and distant, muffled heart sounds.[1]

Physiology

The fall in arterial blood pressure results from pericardial fluid accumulation inside the pericardial sac, which decreases the maximum size of the ventricles. This limits diastolic expansion (filling) which results in a lower EDV (End Diastolic Volume) which reduces stroke volume, a major determinant of systolic blood pressure. This is in accordance with the Frank-Starling law of the heart, which explains that as the ventricles fill with larger volumes of blood, they stretch further, and their contractile force increases, thus causing a related increase in systolic blood pressure.

The rising central venous pressure is evidenced by distended jugular veins while in a non-supine position. It is caused by reduced diastolic filling of the right ventricle, due to pressure from the adjacent expanding pericardial sac. This results in a backup of fluid into the veins draining into the heart, most notably, the jugular veins. In severe hypovolemia, the neck veins may not be distended.[4]

The suppressed heart sounds occur due to the muffling effects of the fluid surrounding the heart.

Clinical use

Although the full triad is present only in a minority of cases of acute cardiac tamponade,[5] presence of the triad is considered pathognomonic for the condition.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 Camm, Christian Fielder; Camm, A. John (2016). "1. Examination techniques". Clinical Guide to Cardiology. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-118-75533-4. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-05-28.

- ↑ Beck CS (1935). "Two cardiac compression triads". JAMA. 104 (9): 714–716. doi:10.1001/jama.1935.02760090018005.

- ↑ Case faculty Claude Beck - "Biography of Claude S. Beck". Archived from the original on 2009-03-07. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ Taghavi, Sharven; Askari, Reza (2022), "Hypovolemic Shock", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30020669, archived from the original on 2021-05-06, retrieved 2022-05-09

- ↑ Sternbach G (1988). "Claude Beck: cardiac compression triads". J Emerg Med. 6 (5): 417–419. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(88)90017-0. PMID 3066820.

- ↑ Demetriades D (1986). "Cardiac wounds. Experience with 70 patients". Ann. Surg. 203 (3): 315–317. doi:10.1097/00000658-198603000-00018. PMC 1251098. PMID 3954485.