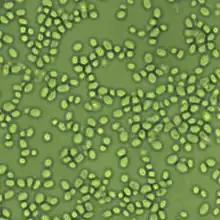

Candida glabrata

| Candida glabrata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nakaseomyces glabrata 1600x | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Saccharomycetes |

| Order: | Saccharomycetales |

| Family: | Saccharomycetaceae |

| Genus: | Candida |

| Species: | C. glabrata |

| Binomial name | |

| Candida glabrata (H.W.Anderson) S.A.Mey. & Yarrow (1978) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cryptococcus glabratus H.W.Anderson (1917) | |

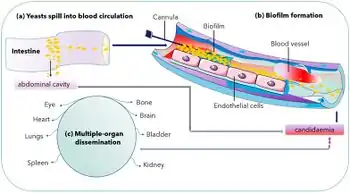

Candida glabrata is a species of haploid yeast of the genus Candida, previously known as Torulopsis glabrata. Despite the fact that no sexual life cycle has been documented for this species, C. glabrata strains of both mating types are commonly found.[1] C. glabrata is generally a commensal of human mucosal tissues, but in today's era of wider human immunodeficiency from various causes (for example, therapeutic immunomodulation, longer survival with various comorbidities such as diabetes, and HIV infection), C. glabrata is often the second or third most common cause of candidiasis as an opportunistic pathogen.[2] Infections caused by C. glabrata can affect the urogenital tract or even cause systemic infections by entrance of the fungal cells in the bloodstream (Candidemia), especially prevalent in immunocompromised patients.[2]

Phylogenetic relationship

The currently assigned genus name of Candida can lead to confusion. Compared with other potential pathogens of the genus (such as C. albicans or C. auris), C. glabrata is more closely related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In fact, C. glabrata belongs to the group of Nakaseomyces inside the whole genome duplication clade within Saccharomycetaceae.[3] The whole genome duplication event occurred about 90 million years ago, whereas phylogenetic studies indicate that the common ancestor between C. glabrata and C. albicans is dated between 200 and 300 million years ago. The largest phylogenetic study to date about Saccharomycotina, also known as budding yeasts, indicated in 2018 that the (currently construed) genus Candida is found in Pichiaceae, CUG-Ser1 clade, Phaffomycetaceae and Saccharomycetaceae. Consequently, despite that the name Candida evokes a unitary notion of candidiasis, the pathogenic power of some budding yeasts is a paraphyletic trait shared by several subphyla with different kinds of metabolism.[4]

Clinical relevance

Candida glabrata is of special relevance in nosocomial infections due to its innately high resistance to antifungal agents, specifically the azoles.[2] Besides its innate tolerance to antifungal drugs, other potential virulence factors contribute to C. glabrata pathogenicity. One of them is the expression of a series of adhesins genes.[5] These genes, which in C. glabrata are mostly encoded in the subtelomeric region of the chromosome, have their expression highly activated by environmental cues, so that the organism can adhere to biotic and abiotic surfaces in microbial mats. Adhesin expression is the suspected first mechanism by which C. glabrata forms fungal biofilms, proved to be more resistant to antifungals than the planktonic cells.[6]

Candida glabrata genome frequently undergoes rearrangements that are hypothesized to contribute to the improvement of this yeast's fitness towards exposure to stressful conditions, and some authors consider that this property is connected to the virulence potential of this yeast.[7]

Diagnosis

Cultures are an effective method for identifying non-albicans vaginal infections. Urinalyses are less accurate in this process. The culture may take several days to grow, but the identification of the yeast species is quick once the yeast is isolated. Skin disease diagnosis is difficult, as cultures collected from swabs and biopsies will test negative for fungus and a special assessment is required. Listed under the 'Rare Diseases' database on the NIH web site, Torulopsis glabrata, or Candida glabrata can also be found on the CDC's web site.[8] Although listed as the second most virulent yeast after Candida albicans, the fungus is becoming more and more resistant to common treatments like fluconazole. Like many Candida species, C. glabrata resistance to Echinocandin is also increasing, leaving expensive and toxic antifungal treatments available for those infected.[8] Although high mortality rates are listed, assessment of the critical nature of a glabrata infection is a gray area.

Candida glabrata ferments and assimilates only glucose and trehalose, opposing to other Candida species and this repertoire of sugar utilization is used by several commercially available kits for identification.[9]

Treatment

A major phenotype and potential virulence factor that C. glabrata possesses is low-level intrinsic resistance to the azole medications, which are the most commonly prescribed antifungal (antimycotic) medications. These medications, including fluconazole and ketoconazole, are "not effective in 15–20% of cases"[2] against C. glabrata. It is still highly vulnerable to polyene medications such as amphotericin B and nystatin, along with variable vulnerability to flucytosine and caspofungin. However, intravenous amphotericin B is a medication of last resort, causing among other side effects, chronic kidney failure. Amphotericin B vaginal suppositories are used as an effective form of treatment in combination with boric acid capsules as they are not absorbed into the bloodstream.

A first-line treatment for vaginal infections may be the use of terconazole 7-day cream. Several courses may be needed. The cure-rate for this treatment is approximately 40%. Recurrences are common, causing chronic infections and spread to other areas such as skin and scalp. Blood infections might be best assessed per symptoms if other areas are involved.

An experimental, but effective second-line treatment for chronic infections, is the use of boric acid. Compounding pharmacies can create boric acid vaginal suppositories. Use of Vitamin E oil may be used in conjunction to combat irritation. Amphotericin B vaginal suppositories have also been used in case studies to treat chronic infections, both symptomatic and asymptomatic. Borax and boric acid may be used for persistent scalp and skin infections.

References

- ↑ Fairhead, Cécile; Dujon, Bernard; Gallaud, Julien; Hennequin, Christophe; Muller, Héloïse (2008-05-01). "The Asexual Yeast Candida glabrata Maintains Distinct a and α Haploid Mating Types". Eukaryotic Cell. 7 (5): 848–858. doi:10.1128/EC.00456-07. ISSN 1535-9778. PMC 2394967. PMID 18375614.

- 1 2 3 4 Fidel, Paul L.; Vazquez, Jose A.; Sobel, Jack D. (1999). "Candida glabrata: Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Disease with Comparison to C. albicans". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 12 (1): 80–96. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.1.80. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 88907. PMID 9880475.

- ↑ Gabaldón, Toni; Martin, Tiphaine; Marcet-Houben, Marina; Durrens, Pascal; Bolotin-Fukuhara, Monique; Lespinet, Olivier; Arnaise, Sylvie; Boisnard, Stéphanie; Aguileta, Gabriela; Atanasova, Ralitsa; Bouchier, Christiane (2013-09-14). "Comparative genomics of emerging pathogens in the Candida glabrata clade". BMC Genomics. 14 (1): 623. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-623. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 3847288. PMID 24034898.

- ↑ Shen, Xing-Xing; Opulente, Dana A.; Kominek, Jacek; Zhou, Xiaofan; Steenwyk, Jacob L.; Buh, Kelly V.; Haase, Max A. B.; Wisecaver, Jennifer H.; Wang, Mingshuang; Doering, Drew T.; Boudouris, James T. (2018-11-29). "Tempo and Mode of Genome Evolution in the Budding Yeast Subphylum". Cell. 175 (6): 1533–1545.e20. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.023. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 6291210. PMID 30415838.

- ↑ Michael, de Groot, Piet W. J. Kraneveld, Eefje A. Yin, Qing Yuan Dekker, Henk L. Groß, Uwe Crielaard, Wim de Koster, Chris G. Bader, Oliver Klis, Frans M. Weig. The Cell Wall of the Human Pathogen Candida glabrata: Differential Incorporation of Novel Adhesin-Like Wall Proteins ▿ †. American Society for Microbiology (ASM). OCLC 677694114.

- ↑ Cavalheiro, Mafalda; Teixeira, Miguel Cacho (2018). "Candida Biofilms: Threats, Challenges, and Promising Strategies". Frontiers in Medicine. 5: 28. doi:10.3389/fmed.2018.00028. ISSN 2296-858X. PMC 5816785. PMID 29487851.

- ↑ Ahmad, Khadija M; Kokošar, Janez; Guo, Xiaoxian; Gu, Zhenglong; Ishchuk, Olena P; Piškur, Jure (June 2014). "Genome structure and dynamics of the yeast pathogen Candida glabrata". FEMS Yeast Research. 14 (4): 529–535. doi:10.1111/1567-1364.12145. ISSN 1567-1356. PMC 4320752. PMID 24528571.

- 1 2 "Antifungal Resistance". Fungal Diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 June 2017. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ↑ Bonnin, Alain; Vagner, Odile; Cuisenier, Bernadette; Pacot, Agnès; Nierlich, Anne-Charlotte; Moiroux, Philippe; Mantelin, Pierre; Dalle, Frédéric; Lopez, José (2001-03-01). "Rapid Identification of Candida glabrata Based on Trehalose and Sucrose Assimilation Using Rosco Diagnostic Tablets". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 39 (3): 1172–1174. doi:10.1128/JCM.39.3.1172-1174.2001. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 87898. PMID 11230452.

External links

- Candida genome database Archived 2016-11-18 at the Wayback Machine

- PathoYeastract Archived 2019-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Candida glabrata genome map Archived 2023-06-30 at the Wayback Machine