Choroidal neovascularization

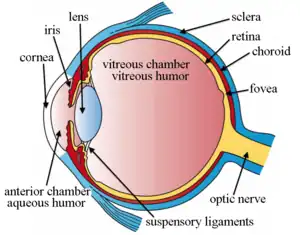

Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) is the creation of new blood vessels in the choroid layer of the eye. Choroidal neovascularization is a common cause of neovascular degenerative maculopathy (i.e. 'wet' macular degeneration)[1] commonly exacerbated by extreme myopia, malignant myopic degeneration, or age-related developments.

Causes

CNV can occur rapidly in individuals with defects in Bruch's membrane, the innermost layer of the choroid. It is also associated with excessive amounts of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). As well as in wet macular degeneration, CNV can also occur frequently with the rare genetic disease pseudoxanthoma elasticum and rarely with the more common optic disc drusen. CNV has also been associated with extreme myopia or malignant myopic degeneration, where in choroidal neovascularization occurs primarily in the presence of cracks within the retinal (specifically) macular tissue known as lacquer cracks.

Symptoms

CNV can create a sudden deterioration of central vision, noticeable within a few weeks. Other symptoms which can occur include color disturbances, and metamorphopsia (distortions in which straight lines appear wavy). Hemorrhaging of the new blood vessels can accelerate the onset of symptoms of CNV. CNV may also include the feeling of pressure behind your eye.

Using modern optical coherence tomography devices, it is possible to detect non-exudative neovascular membranes, that are typically asymptomatic.[2][3][4]

Identification

CNV can be detected by using a type of perimetry called preferential hyperacuity perimetry.[5] On the basis of fluorescein angiography, CNV may be described as classic or occult. Two other tests that help identify the condition include indocyanine green angiography and optical coherence tomography.[6]

Treatment

CNV is conventionally treated with intravitreal injections of angiogenesis inhibitors (also known as "anti-VEGF" drugs) to control neovascularization and reduce the area of fluid below the retinal pigment epithelium. Angiogenesis inhibitors include pegaptanib, ranibizumab and bevacizumab (known by a variety of trade names, such as Macugen, Avastin or Lucentis). These inhibitors slow or stop the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis), typically by binding to or deactivating the transmission of vascular endothelial growth factor ('VEGF'), a signal protein produced by cells to stimulate formation of new blood vessels. The effectiveness of angiogenesis inhibitors has been shown to significantly improve visual prognosis with CNV, the recurrence rate for these neovascular areas remains high.[7]

CNV may also be treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT) coupled with a photosensitive drug such as verteporfin (Visudyne). The drug is given intravenously. It is then activated in the eye by a laser light. The drug destroys the new blood vessels, and prevents any new vessels forming by forming thrombi.[8] A Cochrane Review published in 2016 found that people with severe myopia (short-sightedness or near-sightedness) may benefit from being given anti-VEGF treatment.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Spalton DJ, Hitchings RA, Hunter PA (2005). Atlas of Clinical Ophthalmology (3rd ed.).

- ↑ Querques G, Srour M, Massamba N, Georges A, Ben Moussa N, Rafaeli O, Souied EH (October 2013). "Functional characterization and multimodal imaging of treatment-naive "quiescent" choroidal neovascularization". Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 54 (10): 6886–92. doi:10.1167/iovs.13-11665. PMID 24084095.

- ↑ Pfau M, Möller PT, Künzel SH, von der Emde L, Lindner M, Thiele S, Dysli C, Nadal J, Schmid M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Holz FG, Fleckenstein M (March 2020). "Type 1 Choroidal Neovascularization Is Associated with Reduced Localized Progression of Atrophy in Age-Related Macular Degeneration". Ophthalmol Retina. 4 (3): 238–248. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2019.09.016. PMID 31753808.

- ↑ Roisman L, Zhang Q, Wang RK, Gregori G, Zhang A, Chen CL, Durbin MK, An L, Stetson PF, Robbins G, Miller A, Zheng F, Rosenfeld PJ (June 2016). "Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography of Asymptomatic Neovascularization in Intermediate Age-Related Macular Degeneration". Ophthalmology. 123 (6): 1309–19. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.044. PMC 5120960. PMID 26876696.

- ↑ Alster Y, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Brimacombe JA, Crompton RM, Duh YJ, Gabel VP, Heier JS, Ip MS, Loewenstein A, Packo KH, Stur M, Toaff T (October 2005). "Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter (PreView PHP) for detecting choroidal neovascularization study". Ophthalmology. 112 (10): 1758–65. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.06.008. PMID 16154198.

- ↑ Reddy U, Kryzstolik M (January 2006). "Antiangiogenic therapy with interferon alfa for neovascular age-related macular degeneration". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005138. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005138.pub2. PMID 16437522.

- ↑ Takeda AL, Colquitt J, Clegg AJ, Jones J (September 2007). "Pegaptanib and ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 91 (9): 1177–82. doi:10.1136/bjo.2007.118562. PMC 1954893. PMID 17475698.

- ↑ Donati G (2007). "Emerging therapies for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: state of the art". Ophthalmologica. Journal International d'Ophtalmologie. International Journal of Ophthalmology. Zeitschrift für Augenheilkunde. 221 (6): 366–77. doi:10.1159/000107495. PMID 17947822.

- ↑ Zhu Y, Zhang T, Xu G, Peng L (December 2016). "Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for choroidal neovascularisation in people with pathological myopia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD011160. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011160.pub2. PMC 6464015. PMID 27977064.