Coccydynia

| Coccydynia | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Coccyx pain, coccygodynia, coccygeal pain, coccalgia, tailbone pain[1][2] | |

| |

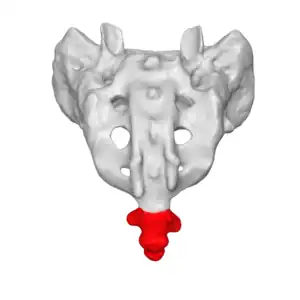

| The location of the coccyx (in red) at the lower aspect of the sacrum of the pelvis | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | Tailbone pain[2] |

| Types | Acute < 2 month; chronic > 2 month[1] |

| Causes | Injury, infection, cancer, referred pain[2] |

| Risk factors | Obesity, childbirth[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, supported by medical imaging[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pilonidal cyst, piriformis syndrome , hemorrhoids, pelvic floor disorder[1][2] |

| Treatment | Avoiding sitting, using cushions, pain medication, surgery[2] |

| Prognosis | Generally good[2] |

| Frequency | Common[3] |

Coccydynia is pain in the tailbone area, the lowest part of the low back.[1][2] Pain is generally increased with sitting, having a bowel movement, or rising after sitting.[1] Pain in other parts of the back and radiation of pain is generally absent.[1]

Causes may include injury, infection, cancer, or referred pain.[2] Types of injury include contusions, fractures, dislocations, and ligament injury.[2] Risk factors include obesity and childbirth.[1][2] Referred pain may occur in the tailbone from the gastrointestinal or urogenital tract.[2] Diagnosis is based on symptoms and may be supported by medical imaging.[1]

Treatment involves avoiding sitting, using cushions, and pain medication.[2] Physiotherapy or injections of methylprednisolone and bupivicaine may be helpful.[1] Rarely surgery to remove the coccyx may be carried out.[2] Most people get better within weeks to months, regardless of treatment.[2]

Coccydynia is common.[3] Onset is most commonly around the age of 40 and women are more commonly affected than men.[1] The term was introduced in 1859 by Simpson.[2] Descriptions of the condition; however, date back to the 1500s.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Activities that put pressure on the affected area are bicycling, horseback riding, and other activities such as increased sitting that put direct stress on the coccyx. The medical condition is often characterized by pain that worsens with constipation and may be relieved with bowel movement. Rarely, even sexual intercourse can aggravate symptoms.

Causes

One way of classifying is whether the onset was traumatic versus non-traumatic. In many cases the exact cause is unknown and is referred to as idiopathic coccydynia.

Coccydynia is a fairly common injury which can often result from falls, particularly in leisure activities such as cycling and skateboarding. Coccydynia is often reported following a fall or after childbirth. In some cases, persistent pressure from activities like bicycling may cause the onset of coccyx pain.[4] Coccydynia due to these causes usually is not permanent, but it may become very persistent and chronic if not controlled. Coccydynia may also be caused by sitting improperly thereby straining the coccyx.

Rarely, coccydynia is due to the undiagnosed presence of a sacrococcygeal teratoma or other tumor in the vicinity of the coccyx.[1]

Pathophysiology

There are common pathophysiological ways that a person may develop coccydynia. The two main causes for this condition are sudden impact due to fall, and coccydynia caused by childbirth pressure in women.[5] Other ways that coccydynia develops are partial dislocation of the sacrococcygeal synchondrosis that can possibly result in abnormal movement of the coccyx from excessive sitting, and repetitive trauma of the surrounding ligaments and muscles, resulting in inflammation of tissues and pain.

Structure

Coccydynia occurs in the lowest part of the spine, the coccyx, which is believed to be a vestigial tail, or in other words the “tail bone”. The name coccyx is derived from the Greek word for cuckoo due to its beak like appearance. The coccyx itself is made up of 3 to 5 vertebrae, some of which may be fused together. The ventral side of the coccyx is slightly concave whereas the dorsal aspect is slightly convex. Both of these sides have transverse grooves that show where the vestigial coccygeal units had previously fused. The coccyx attaches to the sacrum from the dorsal grooves, with the attachment being either a symphysis or as a true synovial joint, and also to the gluteus maximus muscle, the coccygeal muscle, and the anococcygeal ligament.

Orientations

There are four different orientations for the coccyx, as described by Postacchini and Massobrio. In type I the coccyx is curved anteriorly with its apex facing downward and caudally. In type II this forward curvature is more dramatic and the apex extends forward. Type III is where the coccyx angles forward sharply. Lastly, type IV is characterized by the coccyx being subluxated at the sacrococcygeal joint.

Diagnosis

A number of different conditions can cause pain in the general area of the coccyx, but not all involve the coccyx and the muscles attached to it. The first task of diagnosis is to determine whether the pain is related to the coccyx. Physical rectal examination, high resolution x-rays and MRI scans can rule out various causes unrelated to the coccyx, such as Tarlov cysts and pain referred from higher up the spine. Note that, contrary to most anatomical textbooks, most coccyxes consist of several segments: 'fractured coccyx' is often diagnosed when the coccyx is in fact normal or just dislocated at an intercoccygeal joint.[6][7]

A simple test to determine whether the coccyx is involved is injection of local anesthetic into the area. If the pain relates to the coccyx, this should produce immediate relief.[8]

If the anesthetic test proves positive, then a dynamic (sit/stand) x-ray or MRI scan may show whether the coccyx dislocates when the patient sits.[9]

Use of dynamic x-rays on 208 patients who gave positive results with the anesthetic test showed:

- 31% Not possible to identify the cause of pain

- 27% Hypermobility (excessive flexing of the coccyx forwards and upwards when sitting)

- 22% Posterior luxation (partial dislocation of the coccyx backwards when sitting)

- 14% Spicule (bony spur) on the coccyx

- 5% Anterior luxation (partial dislocation of the coccyx forwards when sitting)

This study found that the pattern of lesions was different depending on the obesity of the patients: obese patients were most likely to have posterior luxation of the coccyx, while thin patients were most likely to have coccygeal spicules.

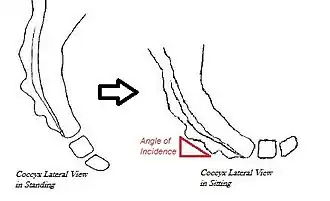

Angle of incidence

Sagittal coccygeal movement is measured using the angle of incidence—or the angle at which the coccyx strikes the seat when an individual sits down.[10] A smaller angle indicates the coccyx being more parallel to the seat, resulting in flexion (or “normal” movement) of the coccyx.[10] A larger angle indicates the coccyx being more perpendicular to the seat, causing posterior subluxation (or “backward” movement) of the coccyx.[10]

Prevention

Body positioning and alignment is significant for producing less stress in the coccyx region. Bad posture can influence coccyx pain. People may not realize that they are over stressing their coccyx while doing daily activities. Pain in the coccyx can be caused from many incidents like falling, horseback riding, or even sitting on hard surfaces for a long period of time. The main focus is to prevent coccyx pain from occurring, by correcting everyday activities that contribute to tailbone pain. You can take hot or cold water baths. Have a stream of hot or cold water run down your back continuously if pain becomes unbearable. Use cold water if pain persists. Repeat the procedure in intervals of 5-6 minutes.

Equipment use

There is no definite way to fully prevent coccyx pain because an accident can occur at any given time. However, people who are obese are at a higher risk for developing coccyx pain. Carrying excessive weight contributes to more stress on the coccyx while sitting down causing increased chances of pain.[11] Prevention of carrying excessive weight gain can help reduce the tension and pressure on the coccyx. In other words, the coccyx for obese people may be more posteriorly outward when they are sitting down.[11] Avoidance of contact sports like basketball, football, and or hockey can decrease the risks of coccyx pain, because it can help reduce the chances of falling. Another method is proper safety equipment for sports is to prevent coccyx pain. For example, there are hockey pants that provide extra cushion that protect the thigh, coccyx, and buttocks. These results will lead to less falls that can cause trauma to the coccyx.

Physiotherapy

A kneeling groin stretch can help prevent coccyx pain from occurring after long periods of sitting. The adductor magnus is involved in the kneeling groin stretch, and when it is tight it can contribute to tailbone pain, so stretching can help prevent tailbone pain. Other stretches like piriformis stretch, and hands to feet stretch, can relieve stress off the muscles around the coccyx, after sitting for a long time. These release tension built up around the muscles in the coccyx.

Treatment

Since sitting on the affected area may aggravate the condition, a cushion with a cutout at the back under the coccyx is recommended. If there is tailbone pain with bowel movements, then stool softeners and increased fiber in the diet may help. Anti-inflammatory medications such as NSAIDS may be prescribed.[1]

If the pain persists, other treatments may be applied. Manual treatment is carried out by repeated massage of the muscles attached to the coccyx, via the anus. Such treatment is usually given by an intimate partner, chiropractor, osteopath or physical therapist. Thiele applied this treatment to a series of 169 coccydynia patients, and reported 63% cured.[12]

Orthopaedic surgeons commonly inject corticosteroids into the painful joint. Maigne and Tamalet applied this treatment to 86 patients under fluoroscopic guidance.[13] Two months after the injection, 50% of the patients with luxation or hypermobility were improved or healed, but only 27% of the patients with no visible abnormality improved. Where an abnormality had been found, and injection relieved the pain, the abnormality remained but ceased to be painful.

Temporary or permanent nerve blocks are sometimes applied in cases of coccydynia. Foye et al reported that repeated temporary nerve blocks by injection at the ganglion impar could give relief in a number of cases, and occasionally a single injection was sufficient.[14]

Surgery

If non-surgical treatments fail to relieve the pain, or in cases of cancer, surgery to remove the coccyx (coccygectomy) may be required. In cases where pain persists after surgery, standard drugs for chronic pain, such as tri-cyclic anti-depressants, may help alleviate the pain.[15]

Epidemiology

A study of 2000 cases of back pain referred to hospital found that 2.7% were diagnosed as coccydynia.[16] This type of pain occurs five times more frequently in women than in men. It can occur at any age, the mean age of onset being around 40.[1] There are no ethnicity or race associations with coccydynia.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Patel, R; Appannagari, A; Whang, P.G. (May 2008). "Coccydynia". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 1 (3–4): 223–226. doi:10.1007/s12178-008-9028-1. PMC 2682410. PMID 19468909.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Mabrouk, A; Alloush, A; Foye, P (January 2022). "Coccyx Pain". PMID 33085286.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 Lirette, LS; Chaiban, G; Tolba, R; Eissa, H (2014). "Coccydynia: an overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain". The Ochsner journal. 14 (1): 84–7. PMID 24688338.

- ↑ Foye P, Buttaci C, Stitik T, Yonclas P (2006). "Successful injection for coccyx pain". Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 85 (9): 783–4. doi:10.1097/01.phm.0000233174.86070.63. PMID 16924191.

- ↑ Patel, Ravi, Anoop Appannagari, and Peter G. Whang. "Abstract." National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 07 May 2008. Web. 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Postacchini F, Massobrio M (October 1983). "Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 65 (8): 1116–24. doi:10.2106/00004623-198365080-00011. PMID 6226668.

- ↑ Kim NH, Suk KS (June 1999). "Clinical and radiological differences between traumatic and idiopathic coccygodynia". Yonsei Medical Journal. 40 (3): 215–20. doi:10.3349/ymj.1999.40.3.215. PMID 10412331. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved 2021-10-12.

- ↑ Marx, Fred A. (1996). "Coccydynia/Levator Syndrome, A Therapeutic Test". Techniques in Coloproctology. 4 (1). Archived from the original on 2021-03-09. Retrieved 2021-10-12.

- ↑ Maigne JY, Doursounian L, Chatellier G (December 2000). "Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma". Spine. 25 (23): 3072–9. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012010-00015. PMID 11145819. S2CID 25790826.

- 1 2 3 Maigne, J., Doursounian, L., & Chatellier, G. (2000). Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. SPINE, 25(23), 3072-3079.

- 1 2 Maigne, Jean-Yves, and Doursounian Levon. "Causes and Mechanisms of Common Coccydynia: Role of Body Mass Index and Coccygeal Trauma." Spine Journal 2.5.23 (2000): 3072-3079.

- ↑ Thiele, George H. (1963). "Coccygodynia: Cause and treatment". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 6 (6): 422–436. doi:10.1007/bf02633479. PMID 14082980. S2CID 35310988.

- ↑ Maigne, JY; Tamalet, B (1996). "Standardized radiologic protocol for the study of common coccygodynia and characteristics of the lesions observed in the sitting position". Spine. 21 (22): 2588–93. doi:10.1097/00007632-199611150-00008. PMID 8961446. S2CID 20186649.

- ↑ Foye, P; Buttaci, C; Stitik, T; Yonclas, P (2006). "Successful injection for coccyx pain". Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 85 (9): 783–4. doi:10.1097/01.phm.0000233174.86070.63. PMID 16924191.

- ↑ Onghena, Patrick; Van Houdenhove, Boudewijn (1992). "Antidepressant-induced analgesia in chronic non-malignant pain: a meta-analysis of 39 placebo-controlled studies". Pain. 49 (2): 205–219. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(92)90144-z. PMID 1535121. S2CID 17744448.

- ↑ Ghormley RK (1958). "An Etiologic Study of Back Pain". Radiology. 70 (5): 649–653. doi:10.1148/70.5.649. PMID 13554831.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- www.coccyx.org, website about coccydynia causes, treatments and coping with the condition Archived 2021-08-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Coccyx pain, tailbone pain, coccydynia review article at eMedicine via Medscape Archived 2021-10-16 at the Wayback Machine