Degenerative disc disease

| Degenerative disc disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Degenerative disc disorder, intervertebral disc degeneration | |

| |

| Degenerated disc between C5 and C6 (vertebra at the top of the picture is C2), with osteophytes anteriorly (to the left) on the lower portion of the C5 and upper portion of the C6 vertebral body. | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Risk factors | Connective tissue disease |

Degenerative disc disease (DDD) is a medical condition typically brought on by the normal aging process in which there are anatomic changes and possibly a loss of function of one or more intervertebral discs of the spine.[1] DDD can take place with or without symptoms, but is typically identified once symptoms arise. The root cause is thought to be loss of soluble proteins within the fluid contained in the disc with resultant reduction of the oncotic pressure, which in turn causes loss of fluid volume. Normal downward forces cause the affected disc to lose height, and the distance between vertebrae is reduced. The anulus fibrosus, the tough outer layers of a disc, also weakens. This loss of height causes laxity of the longitudinal ligaments, which may allow anterior, posterior, or lateral shifting of the vertebral bodies, causing facet joint malalignment and arthritis; scoliosis; cervical hyperlordosis; thoracic hyperkyphosis; lumbar hyperlordosis; narrowing of the space available for the spinal tract within the vertebra (spinal stenosis); or narrowing of the space through which a spinal nerve exits (vertebral foramen stenosis) with resultant inflammation and impingement of a spinal nerve, causing a radiculopathy.

DDD can cause mild to severe pain, either acute or chronic, near the involved disc, as well as neuropathic pain if an adjacent spinal nerve root is involved. Diagnosis is suspected when typical symptoms and physical findings are present; and confirmed by x-rays of the vertebral column. Occasionally the radiologic diagnosis of disc degeneration is made incidentally when a cervical x-ray, chest x-ray, or abdominal x-ray is taken for other reasons, and the abnormalities of the vertebral column are recognized. The diagnosis of DDD is not a radiologic diagnosis, since the interpreting radiologist is not aware whether there are symptoms present or not. Typical radiographic findings include disc space narrowing, displacement of vertebral bodies, fusion of adjacent vertebral bodies, and development of bone in adjacent soft tissue (osteophyte formation). An MRI is typically reserved for those with symptoms, signs, and x-ray findings suggesting the need for surgical intervention.

Treatment may include physical therapy for pain relief, ROM, and strength training; stretching exercises; massage therapy; oral analgesia with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDS); and ice and heat.

Signs and symptoms

Degenerative disc disease can result in lower back or upper neck pain. The amount of degeneration does not correlate well with the amount of pain patients experience. Many people experience no pain while others, with the same amount of damage have severe, chronic pain.[2] Whether a patient experiences pain or not largely depends on the location of the affected disc and the amount of pressure that is being put on the spinal column and surrounding nerve roots.

Degenerative disc disease is one of the most common sources of back pain and affects approximately 30 million people every year.[3] With symptomatic degenerative disc disease, the pain can vary depending on the location of the affected disc. A degenerated disc in the lower back can result in lower back pain, sometimes radiating to the hips, and pain in the buttocks, thighs, or legs. If pressure is being placed on the nerves by exposed nucleus pulposus, sporadic tingling or weakness through the knees and legs can occur.

A degenerated disc in the upper neck will often result in pain to the neck, arm, shoulders and hands; tingling in the fingers may also result if nerve impingement is occurring. Pain is most commonly felt or worsened by movements such as sitting, bending, lifting, and twisting.

After an injury, some discs become painful because of inflammation and the pain comes and goes. Some people have nerve endings that penetrate more deeply into the anulus fibrosus (outer layer of the disc) than others, making discs more likely to generate pain. The healing of trauma to the outer anulus fibrosus may also result in the innervation of the scar tissue and pain impulses from the disc, as these nerves become inflamed by nucleus pulposus material. Degenerative disc disease can lead to a chronic debilitating condition and can reduce a person's quality of life. When pain from degenerative disc disease is severe, traditional nonoperative treatment may be ineffective.

Cause

There is a disc between each of the vertebrae in the spine. A healthy, well-hydrated disc will contain a great deal of water in its center, known as the nucleus pulposus, which provides cushioning and flexibility for the spine. Much of the mechanical stress that is caused by everyday movements is transferred to the discs within the spine and the water content within them allows them to effectively absorb the shock. At birth, a typical human nucleus pulposus will contain about 80% water.[4] However natural daily stresses and minor injuries can cause these discs to gradually lose water as the annulus fibrosus, or the tough outer fibrous material of a disc, weakens.[5] Because degenerative disc disease is largely due to natural daily stresses, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists have suggested it is not truly a "disease" process.[6]

This water loss makes the discs more flexible and results in the gradual collapse and narrowing of the gap in the spinal column. As the space between vertebrae gets smaller, extra pressure can be placed on the discs causing tiny cracks or tears to appear in the annulus. If enough pressure is exerted, it is possible for the nucleus pulposus material to seep out through the tears in the annulus and can cause what is known as a herniated disc.

As the two vertebrae above and below the affected disc begin to collapse upon each other, the facet joints at the back of the spine are forced to shift which can affect their function.[7]

Additionally, the body can react to the closing gap between vertebrae by creating bone spurs around the disc space in an attempt to stop excess motion.[8] This can cause issues if the bone spurs start to grow into the spinal canal and put pressure on the spinal cord and surrounding nerve roots as it can cause pain and affect nerve function. This condition is called spinal stenosis.

For women, there is evidence that menopause and related estrogen-loss are associated with lumbar disc degeneration, usually occurring during the first 15 years of the climacteric. The potential role of sex hormones in the etiology of degenerative skeletal disorders is being discussed for both genders.[9]

Mutations in several genes have been implicated in intervertebral disc degeneration. Probable candidate genes include type I collagen (sp1 site), type IX collagen, vitamin D receptor, aggrecan, asporin, MMP3, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6 polymorphisms.[10] Mutation in genes – such as MMP2 and THBS2 – that encode for proteins and enzymes involved in the regulation of the extracellular matrix has been shown to contribute to lumbar disc herniation.[11][12]

Mechanisms

Degenerative discs typically show degenerative fibrocartilage and clusters of chondrocytes, suggestive of repair. Inflammation may or may not be present. Histologic examination of disc fragments resected for presumed DDD is routine to exclude malignancy.

Fibrocartilage replaces the gelatinous mucoid material of the nucleus pulposus as the disc changes with age. There may be splits in the anulus fibrosus, permitting herniation of elements of nucleus pulposus. There may also be shrinkage of the nucleus pulposus that produces prolapse or folding of the anulus fibrosus with secondary osteophyte formation at the margins of the adjacent vertebral body. The pathologic findings in DDD include protrusion, spondylolysis, and subluxation of vertebrae (spondylolisthesis) and spinal stenosis. It has been hypothesized that Cutibacterium acnes may play a role.[13]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of degenerative disc disease will usually consist of an analysis of a patient's individual medical history and an MRI to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other causes.[14]

.png.webp) MRI of the lumbar spine, intervertebral disc degeneration

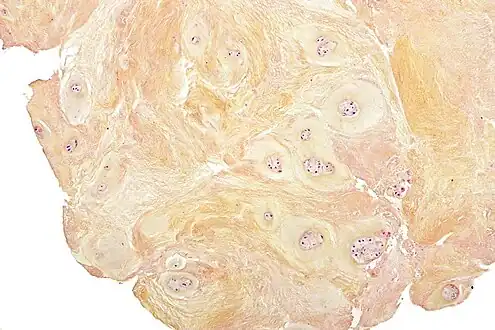

MRI of the lumbar spine, intervertebral disc degeneration Micrograph of a fragment of a resected degenerative vertebral disc, showing degenerative fibrocartilage and clusters of chondrocytes.

Micrograph of a fragment of a resected degenerative vertebral disc, showing degenerative fibrocartilage and clusters of chondrocytes.

Treatment

Often, the symptoms of degenerative disc disease can be treated without surgery. One or a combination of treatments such as physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, traction, or epidural steroid injection can provide adequate relief of troubling symptoms.

Surgery may be recommended if the conservative treatment options do not provide relief within two to three months for cervical or 6 months for lumbar symptoms. If leg or back pain limits normal activity, if there is weakness or numbness in the legs, if it is difficult to walk or stand, or if medication or physical therapy are ineffective, surgery may be necessary, most often spinal fusion. There are many surgical options for the treatment of degenerative disc disease, including anterior[15] and posterior approaches. The most common surgical treatments include:[16]

- Microdiscectomy: A minimally invasive surgical procedure in which a portion of a herniated nucleus pulposus is removed by way of a surgical instrument or laser while using an operating microscope or loupe for magnification.

- Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A procedure that reaches the cervical spine (neck) through a small incision in the front of the neck. The intervertebral disc is removed and replaced with a small plug of bone or other graft substitute, along with a height restoration device to un-impinge nerves, and in time, the vertebrae will fuse together.

- Intervertebral disc arthroplasty: also called Artificial Disc Replacement (ADR), or Total Disc Replacement (TDR), is a type of arthroplasty. It is a surgical procedure in which degenerated intervertebral discs in the spinal column are replaced with artificial ones in the lumbar (lower) or cervical (upper) spine.

- Cervical corpectomy: A procedure that removes a portion of the vertebra and adjacent intervertebral discs to allow for decompression of the cervical spinal cord and spinal nerves. A bone graft, and in some cases a metal plate and screws, is used to stabilize the spine.

- Dynamic Stabilisation: Following a discectomy, a stabilisation implant is implanted with a 'dynamic' component. This can be with the use of Pedicle screws (such as Dynesys or a flexible rod) or an interspinous spacer with bands (such as a Wallis ligament). These devices off load pressure from the disc by rerouting pressure through the posterior part of the spinal column. Like a fusion, these implants allow and maintain mobility to the segment by allowing flexion and extension.

- Facetectomy: A procedure that removes a part of the facet to increase the space.

- Foraminotomy: A procedure that enlarges the vertebral foramen to increase the size of the nerve pathway. This surgery can be done alone or with a laminotomy.

- Intervertebral disc annuloplasty (IDET): A procedure wherein the disc is heated to 90 °C for 15 minutes in an effort to seal the disc and perhaps deaden nerves irritated by the degeneration.

- Laminoplasty: A procedure that reaches the cervical spine from the back of the neck. The spinal canal is then reconstructed to make more room for the spinal cord.

- Laminotomy: A procedure that removes only a small portion of the lamina to relieve pressure on the nerve roots.

- Percutaneous disc decompression: A procedure that reduces or eliminates a small portion of the bulging disc through a needle inserted into the disc, minimally invasive.

- Spinal decompression: A non-invasive procedure that temporarily (a few hours) enlarges the intervertebral foramen (IVF) by aiding in the rehydration of the spinal discs.

- Spinal laminectomy: A procedure for treating spinal stenosis by relieving pressure on the spinal cord. A part of the lamina is removed or trimmed to widen the spinal canal and create more space for the spinal nerves.

Traditional approaches in treating patients with DDD-resultant herniated discs oftentimes include discectomy—which, in essence, is a spine-related surgical procedure involving the removal of damaged intervertebral discs (either whole removal, or partially-based). The former of these two discectomy techniques involved in open discectomy is known as Subtotal Discectomy (SD; or, aggressive discectomy) and the latter, Limited Discectomy (LD; or, conservative discectomy). However, with either technique, the probability of post-operative reherniation exists and at a considerably high maximum of 21%, prompting patients to potentially undergo recurrent disk surgery.[17]

New treatments are emerging that are still in the beginning clinical trial phases. Glucosamine injections may offer pain relief for some without precluding the use of more aggressive treatment options. Adult stem cell or cell transplantation therapies for disc regeneration are in their infancy of development, but initial clinical trials have shown cell transplantation to be safe and initial observations suggest some beneficial effects for associated pain and disability.[18][19] An optimal cell type, transplantation method, cell density, carrier, or patient indication remains to be determined. Investigation into mesenchymal stem cell therapy knife-less fusion of vertebrae in the United States began in 2006[20] and a DiscGenics nucleus pulposus progenitor cell transplantation clinical trial has started as of 2018 in the United States[21] and Japan.[22]

Researchers and surgeons have conducted clinical and basic science studies to uncover the regenerative capacity possessed by the large animal species involved (humans and quadrupeds) for potential therapies to treat the disease.[23] Some therapies, carried out by research laboratories in New York, include introduction of biologically engineered, injectable riboflavin cross-linked high density collagen (HDC-laden) gels into disease spinal segments to induce regeneration, ultimately restoring functionality and structure to the two main inner and outer components of vertebral discs—anulus fibrosus and the nucleus pulposus.[24]

Other animals

Degenerative disc disease can occur in other mammals besides humans. It is a common problem in several dog breeds, and attempts to remove this disease from dog populations have led to several hybrid breeds, such as the Chiweenie.[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Fardon, David F.; Williams, Alan L.; Dohring, Edward J.; Murtagh, F. Reed; Gabriel Rothman, Stephen L.; Sze, Gordon K. (November 2014). "Lumbar Disc Nomenclature: Version 2.0". Spine. 39 (24): E1448–E1465. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a8866d. PMID 23970106. S2CID 8931118.

- ↑ Izzo, R (May 2015). "Spinal Pain". Eur J Radiol. 84 (5): 746–756. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.01.018. PMID 25824642. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ "Degenerative Disc Disease Treament|Degeneratice Disc Disease Treatments". www.instituteforchronicpain.org. Archived from the original on 2017-11-14. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ↑ Kasbia, Virinder (8 September 2005). "Degenerative disc disease". Pembroke Observer. p. 7. ProQuest 354183403.

- ↑ "Degenerative Disc Disease". University of Maryland Medical Center. Archived from the original on 2017-01-05. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- ↑ Emerson AJ, Naze G, Mabry LM, Chaconas E, Silvernail J, Lonnemann E, Rhon D, Deyle GD. "AAOMPT Opposes Use of the Term "Degenerative Disc Disease"". American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists Member's Resources Page. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- ↑ Lee, Yu Chao; Zotti, Mario Giuseppe Tedesco; Osti, Orso Lorenzo (2016). "Operative Management of Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease". Asian Spine Journal. 10 (4): 801–19. doi:10.4184/asj.2016.10.4.801. PMC 4995268. PMID 27559465.

- ↑ "Bone spurs Causes – Mayo Clinic". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2017-09-22. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- ↑ Lou, C.; Chen, H-L.; Feng, X-Z.; Xiang, G-H.; Zhu, S-P.; Tian, N-F.; Jin, Y-L.; Fang, M-Q.; Wang, C.; Xu, H-Z. (December 2014). "Menopause is associated with lumbar disc degeneration: a review of 4230 intervertebral discs". Climacteric. 17 (6): 700–704. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.933409. PMID 25017806. S2CID 20841659.

- ↑ Anjankar SD, Poornima S, Raju S, Jaleel M, Bhiladvala D, Hasan Q. Degenerated intervertebral disc prolapse and its association of collagen I alpha 1 Spl gene polymorphism: A preliminary case control study of Indian population. Indian J Orthop 2015;49:589-94

- ↑ Kawaguchi, Y. (2018). "Genetic background of degenerative disc disease in the lumbar spine". Spine Surgery and Related Research. 2 (2): 98–112. doi:10.22603/ssrr.2017-0007. PMC 6698496. PMID 31440655.

- ↑ Hirose, Yuichiro; et al. (May 2008). "A Functional Polymorphism in THBS2 that Affects Alternative Splicing and MMP Binding Is Associated with Lumbar-Disc Herniation". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (5): 1122–1129. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.013. PMC 2427305. PMID 18455130.

- ↑ Capoor, Manu N.; Ruzicka, Filip; Schmitz, Jonathan E.; James, Garth A.; Machackova, Tana; Jancalek, Radim; Smrcka, Martin; Lipina, Radim; Ahmed, Fahad S.; Alamin, Todd F.; Anand, Neel; Baird, John C.; Bhatia, Nitin; Demir-Deviren, Sibel; Eastlack, Robert K.; Fisher, Steve; Garfin, Steven R.; Gogia, Jaspaul S.; Gokaslan, Ziya L.; Kuo, Calvin C.; Lee, Yu-Po; Mavrommatis, Konstantinos; Michu, Elleni; Noskova, Hana; Raz, Assaf; Sana, Jiri; Shamie, A. Nick; Stewart, Philip S.; Stonemetz, Jerry L.; Wang, Jeffrey C.; Witham, Timothy F.; Coscia, Michael F.; Birkenmaier, Christof; Fischetti, Vincent A.; Slaby, Ondrej (3 April 2017). "Propionibacterium acnes biofilm is present in intervertebral discs of patients undergoing microdiscectomy". PLOS ONE. 12 (4): e0174518. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1274518C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174518. PMC 5378350. PMID 28369127.

- ↑ Farshad-Amacker, Nadja A.; Farshad, Mazda; Winklehner, Anna; Andreisek, Gustav (2015). "MR imaging of degenerative disc disease". European Journal of Radiology. Elsevier BV. 84 (9): 1768–1776. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.04.002. ISSN 0720-048X.

- ↑ Sugawara, Taku (2015). "Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery for Degenerative Disease: A Review". Neurologia Medico-Chirurgica. 55 (7): 540–546. doi:10.2176/nmc.ra.2014-0403. PMC 4628186. PMID 26119899.

- ↑ "Degenerative Disc Disease – When Surgery Is Needed". Archived from the original on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ↑ Shin, Byung-Joon (2014). "Risk factors for recurrent lumbar disc herniations". Asian Spine Journal. 8 (2): 211–215. doi:10.4184/asj.2014.8.2.211. PMC 3996348. PMID 24761206.

- ↑ Schol, Jordy; Sakai, Daisuke (April 2019). "Cell therapy for intervertebral disc herniation and degenerative disc disease: clinical trials". International Orthopaedics. 43 (4): 1011–1025. doi:10.1007/s00264-018-4223-1. PMID 30498909. S2CID 53981159.

- ↑ Sakai, Daisuke; Schol, Jordy (April 2017). "Cell therapy for intervertebral disc repair: Clinical perspective". Journal of Orthopaedic Translation. 9: 8–18. doi:10.1016/j.jot.2017.02.002. PMC 5822958. PMID 29662795.

- ↑ "Mesoblast files spinal fusion IND". Australian Life Scientist. 2006-11-27. Archived from the original on 2009-01-08. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ↑ "NCT03347708". ClinicalTrials.gov. 2 March 2020. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ↑ "DiscGenics Receives Approval from Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency to Begin Clinical Evaluation of Non-Surgical Degenerative Disc Disease Treatment in Japan". PR News Wire. Archived from the original on 2020-12-02. Retrieved 2023-01-23.

- ↑ Moriguchi, Yu; Alimi, Marjan; Khair, Thamina; Manolarakis, George; Berlin, Connor; Bonassar, Lawrence J.; Härtl, Roger (2016). "Biological Treatment Approaches for Degenerative Disk Disease: A Literature Review of In Vivo Animal and Clinical Data". Global Spine Journal. 6 (5): 497–518. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1571955. PMC 4947401. PMID 27433434.

- ↑ Pennicooke, Brenton; Hussain, Ibrahim; Berlin, Connor; Sloan, Stephen R.; Borde, Brandon; Moriguchi, Yu; Lang, Gernot; Navarro-Ramirez, Rodrigo; Cheetham, Jonathan; Bonassar, Lawrence J.; Härtl, Roger (February 2018). "Annulus Fibrosus Repair Using High-Density Collagen Gel: An In Vivo Ovine Model". SPINE. 43 (4): E208–E215. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000002334. PMC 6686199. PMID 28719551.

- ↑ "Chiweenie - Dogs 101 | Animal Planet". www.animalplanet.com. Archived from the original on 2018-03-15. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

External links

| Classification |

|---|